BOJ’s Next Rate Hike Likely Delayed To Early 2025

Nippon Steel Merger Gets Reprieve And, Reportedly, Big Legal Victory

Source: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000032103932&fileKind=1

[FLASH: Nippon Steel got a life-saving reprieve when the Biden White House backpedaled from its intention to formally block NS’ purchase of US Steel on national security grounds. Biden did so in response to an unexpected level of protest not only from business leaders and the security community (including the State and Defense Departments) but also electorally vital communities in Western Pennsylvania that welcome the merger as a job-saver. In the reprieve, the White House granted NS what it had previously denied: an extension of the review by the Committee On Foreign Investment in the US (CIFIUS) so that it could come up with remedies for the alleged national security problems. That moves the deadline for a decision from September 23 to a little while after the November election.

Meanwhile, according to Seeking Alpha, the three arbitrators commissioned by the steel companies and the union intend to give Nippon Steel a complete and unanimous victory. They will reject assertions by the United Steelworkers (USW) union that its merger agreement with US Steel (USS) must be voided because it supposedly violates the union’s contract with USS. The arbitrators’ decision is binding and cannot be appealed by either side. A public announcement is expected sometime around the end of September. Whether this makes the USW more amenable to reaching a deal with Nippon Steel remains to be seen. If not, that would seemingly leave CIFIUS as the only legal way that the merger could be blocked. Since this is now driven entirely by electoral politics, what Biden decides depends on the election's outcome.]

------------------------------------

Almost no one was surprised when the Bank of Japan (BOJ) decided not to raise the overnight interest rate from 0.25% to 0.5% when it met last Friday, Sept. 20. However, almost everyone was surprised when BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda justified the decision by telling a news conference that the BOJ would adopt a wait-and-see stance before making any further moves. He justified this by saying: a) the economic situation, particularly in the US, was too uncertain to make a reasonable decision, a rare departure from Ueda’s usual certitude; b) that financial markets were still too volatile to make a move now (it’s hard for me to see what volatility he was seeing); and c) that another hike had become less urgent because the yen had recovered a substantial part of its weakness. It had strengthened 14% from nearly ¥162/$ in early July to ¥140/$ just a few days before the BOJ meeting, reducing upward pressure on consumer prices in Japan. As a result, said Ueda, “we have some time to decide on policy.”

Ueda’s comments had two consequences. First, market players who had expected the BOJ to raise overnight rates another 0.25% in December now believe the next move won’t come before January. Some say a delay until March seems even more likely. Secondly, the yen reversed, falling by almost 3%, and currently fluctuates around ¥144/$.

The Uncertainty-That-Must-Not-Be-Named

While Ueda was right on the money about many of the uncertainties he named, it is curious that he still refuses to discuss one crucial uncertainty: that inflation, rather than overshooting the BOJ’s 2% target, might undershoot it.

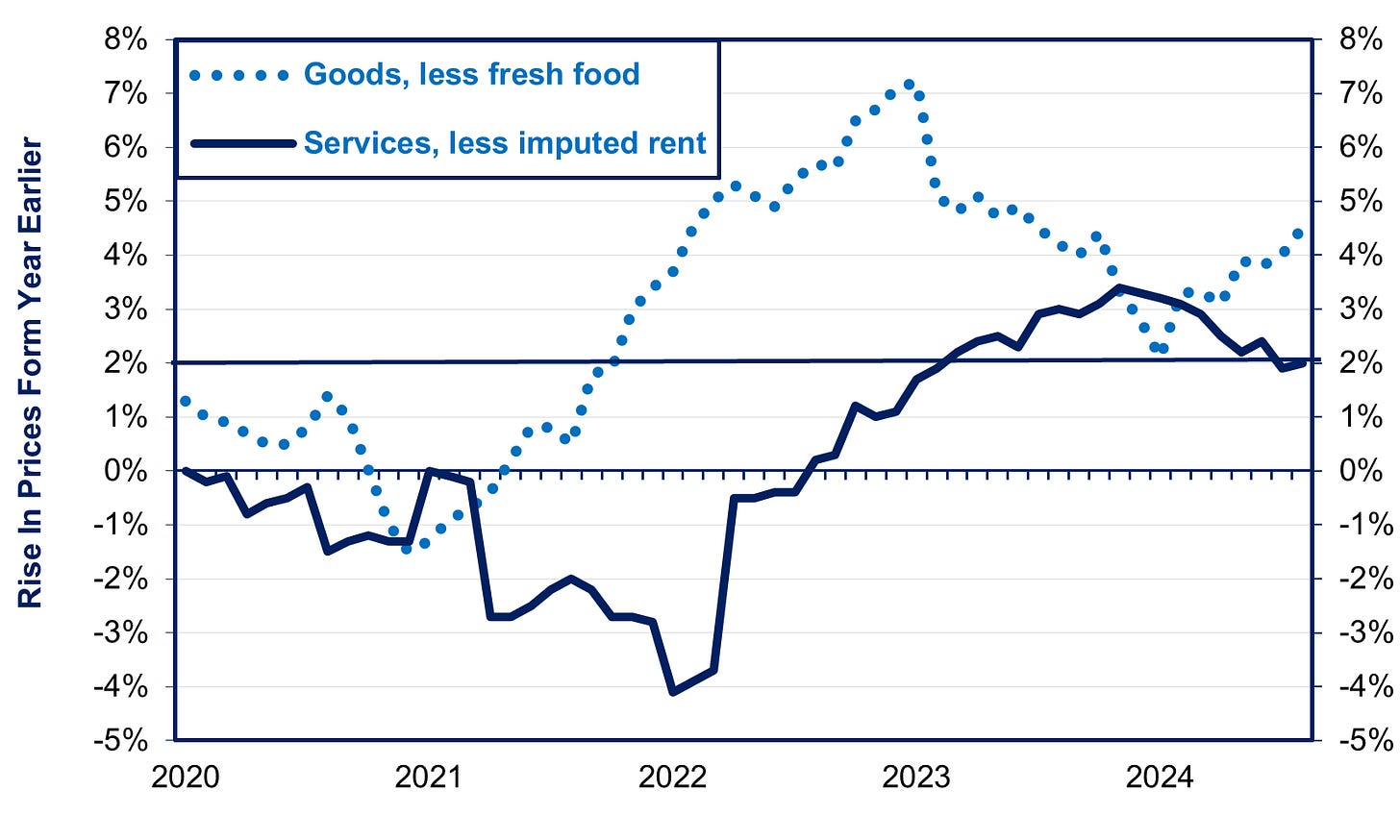

After all, core prices—all items except food and energy—have been decelerating for months, hit their peak in May, and are now dropping. Other measures of headline and core inflation hit their peak in June (see chart at the top). As of August, prices in all these measures are down by about 1% from their peak. If we look at an annualized rate of inflation/deflation in a six-month moving average, we can see that core prices have been decelerating since mid-2023. Since February, core prices have actually been falling by a rate a bit greater than 1% for the first time since Covid. In short, deflation could be back, at least temporarily. At the same time, the BOJ’s favorite measure—all items except for fresh food and energy—has been falling at an annual rate of 0.8% while total headline inflation has been rising at just 0.6%, mainly due to import-intensive items tossed around by the yen rate (see chart below).

Ueda did not even dare to mention this as a risk in light of his propensity to keep repeating the “see no evil” mantra that “Japan's economy is on track and moving in line with our forecasts.” He went even further: “We could have even upgraded our view on inflation expectations, based on domestic data. But uncertainty on the U.S. economic outlook has heightened. That is offsetting some of our optimism on inflation expectations.”

What measures of inflation is Ueda looking at? One such measure is the year-on-year core inflation rate, which is now around 2%, while headline inflation numbers have moved upward (see chart below). This, of course, ignores what has happened since the beginning of 2024.

Secondly, the BOJ sees service prices as a particularly important leading indicator. That’s because many service sectors are far more labor-intensive than goods. So, the BOJ regards this as a good measure of whether wage hikes of 3% are being passed on to customers to achieve 2% inflation (3% wage hikes minus 1% productivity growth equals 2% consumer inflation.) Ueda noted that “service prices are rising in line with our forecast as wages rise.” (see chart below where the numbers in parentheses say the portion of total consumer spending represented by these categories).

Source: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000032103935&fileKind=1

The problem is that nearly half of the service sector index consists of charges by public utilities and prices there have been increasing at a 9% annual rate over the past six months. That distorts the overall picture and I need to investigate this further.

Encouraging News On The Wage Front

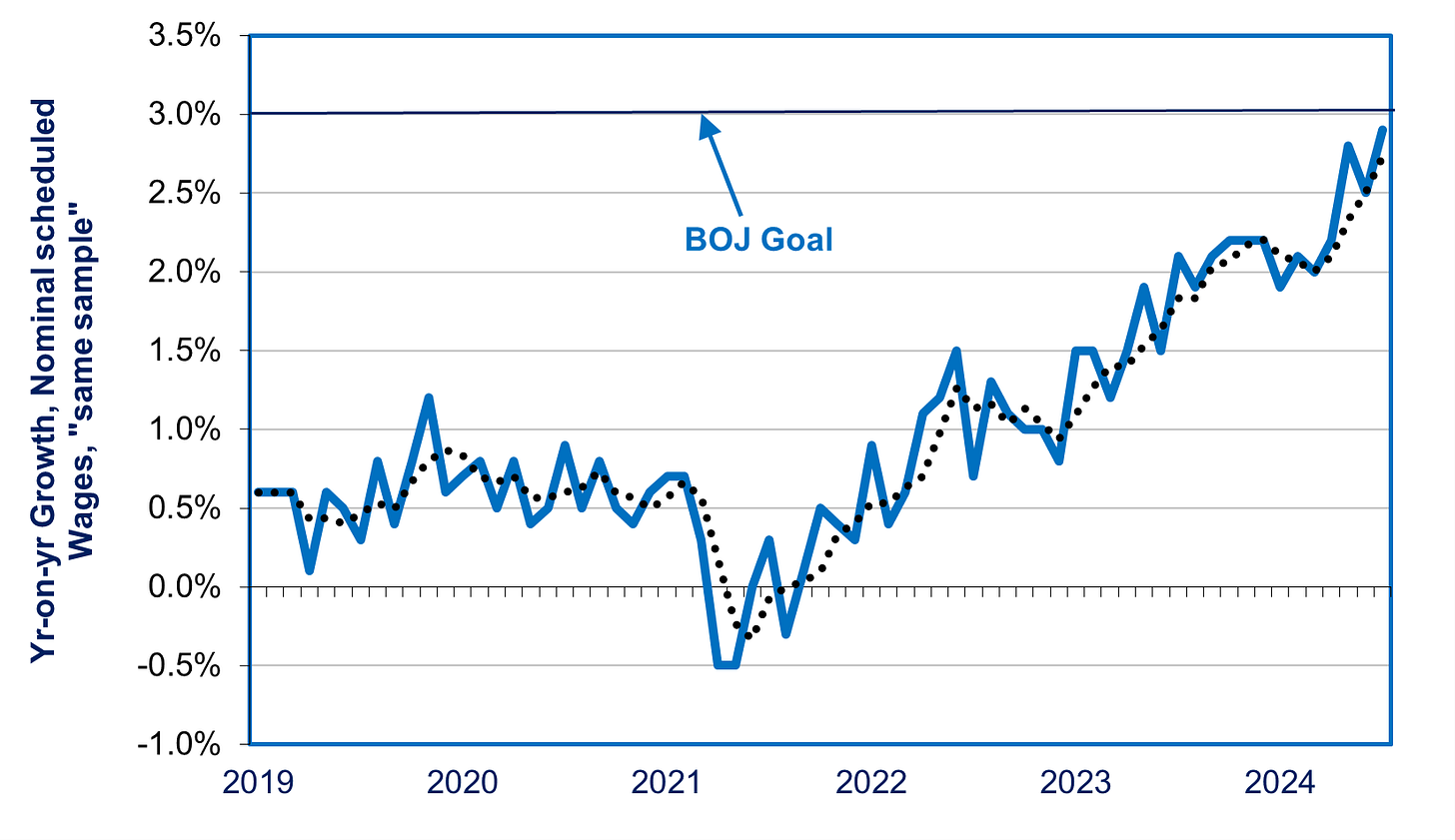

Another source of BOJ confidence is that nominal wages appear to be increasing at the desired 3% annual rate due to the big wage hikes in the spring. The BOJ’s preferred measure is something called the “same sample” index in that the same employers are surveyed each month. But this trend is also confirmed by the broader survey where we can look at wages per scheduled work hours. This measure avoids the distortions caused by bonuses and overtime pay. This, too, is now growing at around 3%. (see following two charts below).

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/30-1a.html

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/monthly-labour.htm

However, there are a couple caveats to be considered. Firstly, as Ueda rightly pointed out, only time will tell whether the big wage hikes seen this year will continue in the following years. “We are hopeful that next year's wage negotiations will be strong. But we must scrutinize how overseas economic developments could affect corporate activity and profits.” Secondly, for wage hikes to translate into the desired 2% inflation, higher nominal wages must translate into higher real wages, which would allow real consumer demand to increase. So far, however, real wage hikes have been rare (see chart below).

My Own Bottom Line

I am not claiming that deflation—or even inflation substantially below 2%—is baked into the cake. All I am saying is that the risks on the inflation front are not one-sided. An undershoot is also possible, and it is strange that Ueda refuses even to discuss the current evidence of softer core prices, even if only to explain why he believes this is just a temporary blip.

The American Economy: Soft Landing, More Inflation, or Lower Growth?

When economies are at turning points, as America’s is now, it’s virtually impossible for economists and policymakers to get policy “just right” in Goldilocks fashion. Even with the best weather satellites and most powerful computers, meteorologists cannot tell you whether it will or won’t rain; they can just say a 28% or 70% chance. And people’s reactions to economic events are far more complicated than the weather. So, the best that central bankers can do is make a judgment call on probabilities and try to balance the risks that they face. Is this a time to err on the side of tightening too much to fight inflation or easing enough to prevent a recession?

So far, the Federal Reserve deserves kudos for pulling off an extremely rare feat: bringing down high inflation without triggering a recession or even a decline in jobs: the so-called soft landing. At present, Fed Chair Jerome Powell says the economy is in good shape, that the risks of too much inflation or too much unemployment are evenly balanced, and his current task is to keep the economy in good shape. That judgment call lay behind his 0.50% cut in the interest rate. He has not made monetary policy “easy,” just less tight. According to the Fed, a neutral overnight interest rate—neither stimulative nor restrictive—is around 3%. Today’s rate after the cut is 4.75% .

Ueda is correct that no one knows for sure what lies in store for the US economy in 2025 and 2026. Some well-regarded US economists fear that inflation will rebound next year or the one after rather than continue to decline to 2% during 2025-26, as the Fed predicts. They contend that both Harris and Trump will expand the budget deficit and therefore upward pressure on prices, and that Trump will do so far more than Harris. These economists say the Fed cut too soon and/or too much and may have to raise rates again in 2025 or so. In contrast, others who are equally well-regarded fear the opposite danger: that the unemployment rate will keep on rising; it has risen from a low of 3.6% in January 2020 to 4.2% as of August. They worry that the Fed has started cutting rates too late.

For what it’s worth, the Fed’s forecasts are not that different from the typical view among private forecasters, as has been the case throughout the period since Covid and Ukraine. Let’s look at the forecasts among the 70 economists surveyed every quarter by the Wall Street Journal. Their latest forecast was in July and the next will come in October. The table below shows the average July forecast and, in parentheses, the range among the central two-thirds of all the predictions.

Source: https://tinyurl.com/bdzzt6xw

The average forecast is pretty much in line with the Fed’s own view, with GDP recovering to 2.1% growth, core inflation down to about 2%, and no further rise in the unemployment rate. Among central two-thirds of the forecasts, the low and high for inflation forecasts are also fairly close to the average, whereas there is a somewhat bigger range when it comes to GDP growth and the unemployment rate. In short, most forecasts see the Fed succeeding in reducing inflation via a soft landing, but some disagreement about how soft it will be.

There is also a market indicator of inflation called TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities). This is a Treasury bond indexed to the rate of inflation. The gap between TIPS bonds and regular bonds—also known as the breakeven rate—shows the market’s expectation of inflation. The market sees inflation for the next five years hitting the Fed’s goal of 2% (see chart below).

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T5YIE

This does not mean that either the forecasters or the markets are right. They can often be wrong, because they regularly extrapolate the future from the present and recent past and they gyrate more than the underlying reality. Still, it does indicate that the Fed’s judgment call is by no means an outlier.

Next Installment: What Does All This Mean For The Yen Rate

On some days on amazon.co.jp