Can Japan Afford To Cut Consumption Tax If It Rolls Back Corporate Tax Cuts?

Corporate Tax Cuts Reduced Gov’t Revenue By A Few Percent of GDP

I received a question about my last post that is worth answering in public because others may have the same question. I had said that, to restore the balance to the division of national income between corporations and households, Japan could roll back its big cuts in corporate taxes and use the new revenue to reverse the big hikes in the consumption tax. Someone asked: can Japan really afford to do that, given its big deficit? The short answer is: yes, it can.

One reason is that the revenue impact from the corporate tax cuts has been far larger than I had suspected: an amount equal to a few percent of GDP. If Tokyo recaptured those lost revenues by restoring the rates of the mid-1990s, it could cut the consumption tax by an amount affecting the same level of revenue. All other things being equal, the impact on overall revenue and the budget deficit would be zero—in the jargon, it’s “revenue-neutral”—it would only affect the source of the revenue, not the total net amount. (In the real world, not all other things are equal, but it’s a close enough estimate to give a sense of the magnitude.)

The Big Loss Of Tax Revenue From Corporate Tax Cuts

Japan cut the top rate of corporate taxes (combined national and local) from 52% in 1994 to 30% these days. Meanwhile, pre-tax profits of nonfinancial corporations zoomed, from 4.5% of GDP in 1994 to a peak of 15% in 2017-18 before coming down in response to the most recent hike in the consumption tax and then COVID.

As a result, even though corporate profits almost tripled—in an economy where nominal GDP was flat—corporate taxes on all corporations were a bit lower in 2019 than in 1994 (see chart above). 2019 is the last year for which we have comparable data. (The tax data includes financial corporations but this is all the data we have available, so this is a rough estimate, but again close to enough to make the point.)

Suppose Japan kept the corporate income tax rate the same as in the mid-1990s. Instead of corporate tax revenue being just 2.6% of GDP as it really was in 2019, it would have been around 6.2% (see chart). That’s a difference equal to 3.6% of GDP.

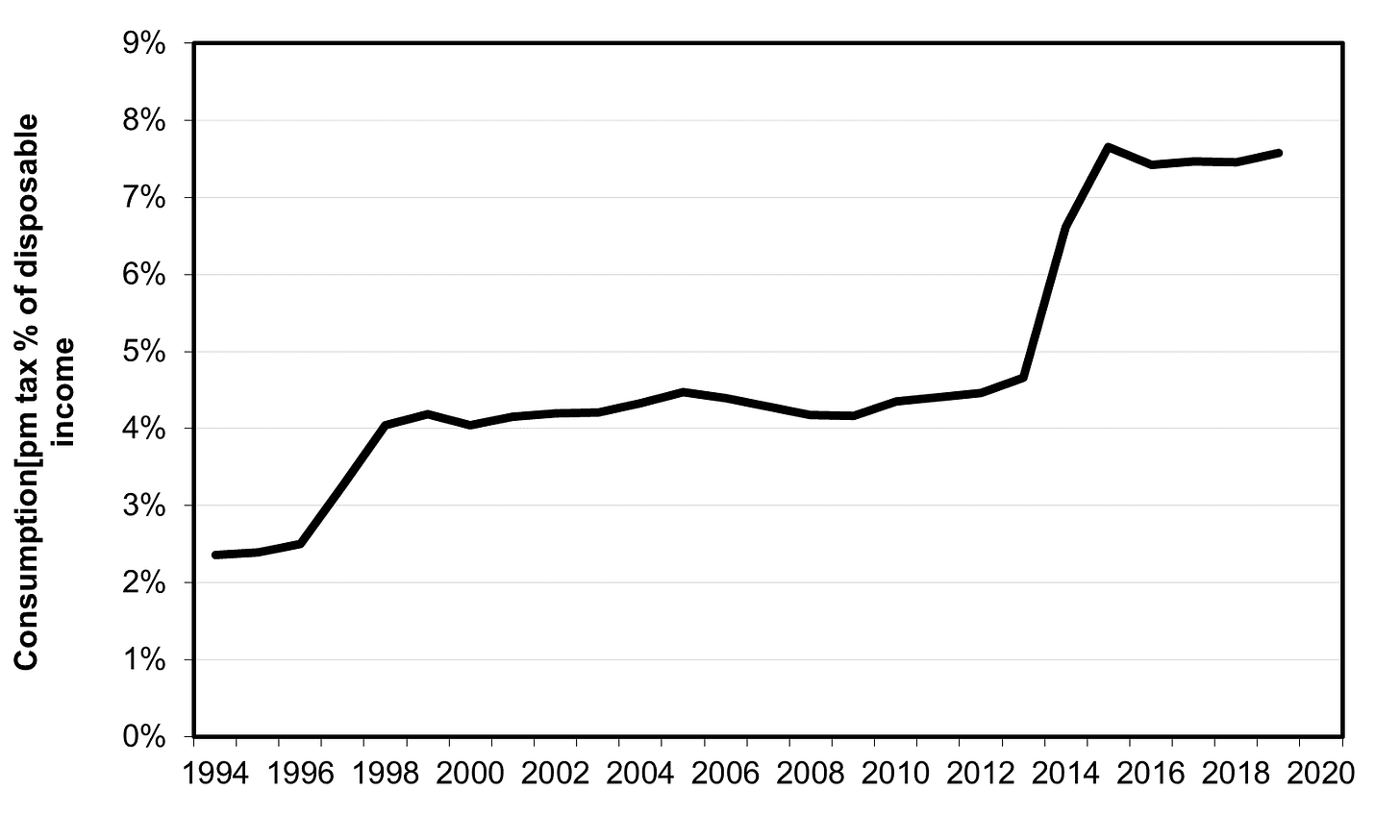

Conversely, the consumption tax, and related excise taxes, rose during 1994-2019 from 2.4% of disposable household income to 7.5% (see chart below). As a percent of GDP, consumption tax revenue rose from 1.4% to 4.1%, a rise equal to 2.7% of GDP.

In short, despite all the talk of the budget deficit, Japan’s leaders were willing to lose more revenue from cuts in corporate taxes than they gained via the hike in the consumption tax (3.6 percent points loss of revenue from corporations vs. a gain of 2.7% from the consumption tax). This, of course, worsened the deficit. No wonder there is so much public resistance to the consumption tax. A tax advertised as being necessary to finance the growing ranks of the elderly was instead used to cut taxes on corporations.

The big sponsors of the corporate tax cut did not expect this result. They believed that cutting corporate taxes would lead to more investment and more wage hikes, thereby increasing nominal GDP and the tax base. That, as we reported in our last post, did not happen. If a country wants to boost corporate investment, an investment tax credit is a lot more effective, at a lot lower reduction of revenues, than a general tax cut.

So, here’s the upshot. Japan is able to have a “revenue-neutral” change in taxes that would help households without raising the budget deficit. It could roll back the corporate tax to mid-1990s rates and use the gain in revenue to roll back the consumption tax just enough to have an equal loss of revenue. That would be a big hike in consumer income and therefore consumer spending. The data makes it clear that, when disposable income rises, people spend more. They do not, as the Finance Ministry sometimes claims, save it all.

Why Did Corporate Profits Rise So Much?

One final point. How did nonfinancial corporations triple their pre-tax profits in an economy where nominal GDP was flat? Hint: it was not from greater efficiency.

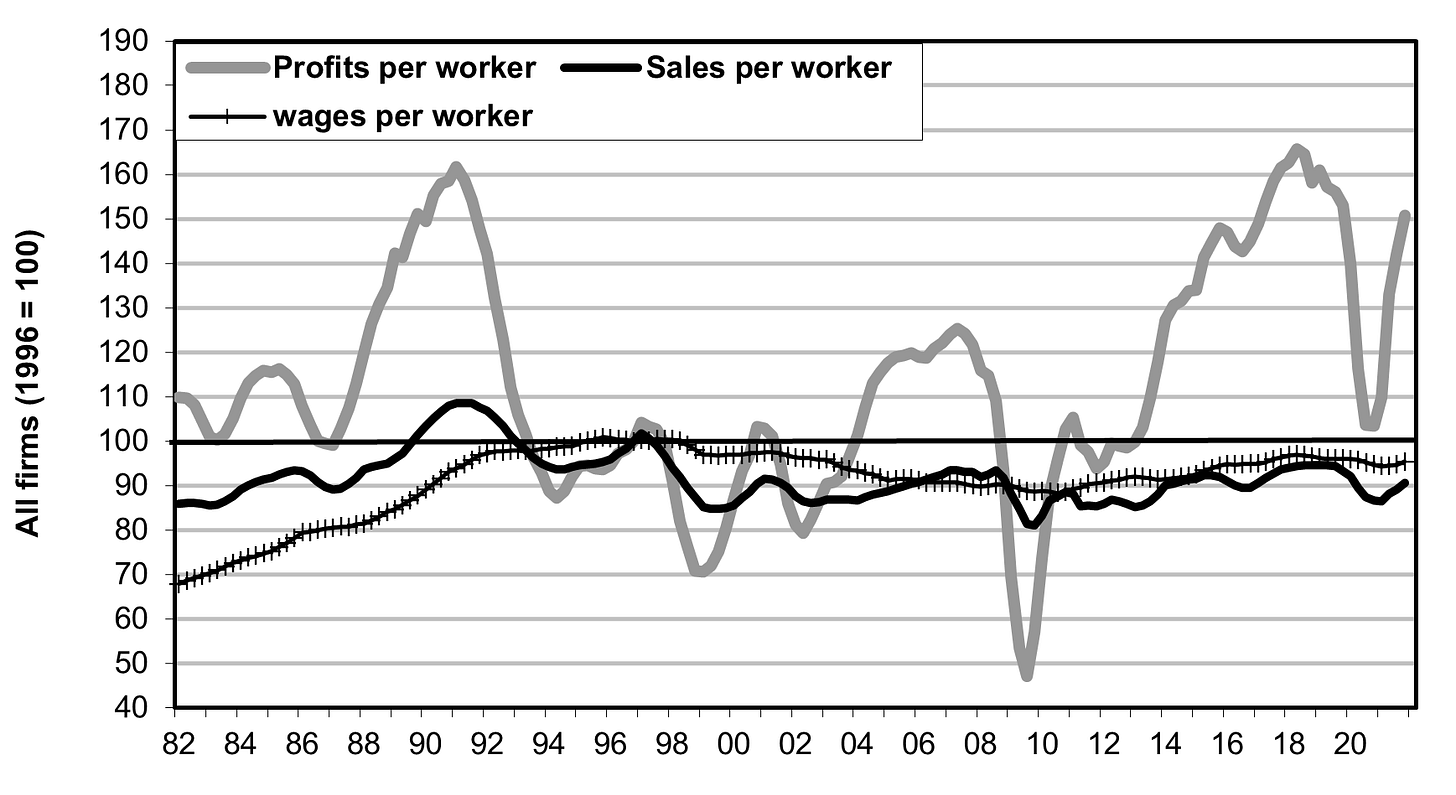

The biggest reason is wage austerity on the part of corporations. In the chart below, we can see that from 1996 through 2021, even though sales per employee fell by 10%, profits per worker rose by 50%. The reason? Corporations cut compensation per worker by 5%, largely by replacing regular workers with lower-paid non-regulars (see chart).

In addition, the big cut in interest rates meant that corporations could keep much more of the profits they earned from their operations rather than turn these profits over to the banks and bondholders. In 1994, the interest rate paid by nonfinancial corporations to banks and bondholders averaged about 4%. As of 2021, it was slightly less than 1%. This also means that households got a lot less interest on their deposits. As of early 2020, the average interest rate on time deposits was just 0.055%. So, if you are like the average household elderly household, you’ve got ¥14.9 million ($110,000) in bank deposits, but those savings bring you a meaningless ¥8,195 ($60)! per year. This is yet another transfer of income from households to corporations. Another hit to consumer demand.

There is no incentive for companies to invest. There is no incentive for companies to pay employees more. There is no incentive for companies to return cash to shareholder.

Until you change the incentives within the system you will not gain any of the goals you are seeking. Taxes are a dis-incentive (Laffer). You tax things that you do not want. That said consumers are not going to spend more if you drop sales taxes because they aren't paid enough to increase spending.

You need to start with the legal system. Japan has to have a more reasonable bankruptcy system. Without this you will never get new business development. Japan is way behind the rest of the world in many ways because too few companies are started.

Banking regulations have to change drastically. You have to promote earnings and risk taking at banks. If you are a loan officer and the company you are lending to goes bankrupt -- the banker's career is ended.

The pension system is owned and operated by the government. They are not risk takers. Returns for the funds is no longer the top priority of the fund managers. You are more likely to lose the business (as a manager) if you don't focus on ESG than is you lose money for the pension. This is stupid and means that there is no incentive for the largest investors to focus on earnings they are forced to focus on ESG. Note there is no good source of information on ESG.

How do you change Japan from a worker mentality to a owner mentality? Without this you will get nowhere.

By the way, Reagan's tax strategy came from President Kennedy... not Mr. Laffer.

First, why would you look at pre-tax profits from "non-financial" companies? I believe the financials pay the same tax rates as other companies. You are skewing the data from the start.

Second, there is no evidence that your plan would be revenue neutral. The great Art Laffer has stated (correctly) you tax things you don't want. If you want to limit consumption -- tax consumption. If you don't want corporate profits -- tax corporate profits.

Lowering corporate taxes encourages business expansion. It makes companies more competitive internationally. Increasing corporate taxes could be a disaster.

There is zero evidence backing your statement that corporate tax revenues would have increased if tax rates had remained at 50%. It is completely possible that revenues would have fallen because the onerous tax rates reduced the earnings of companies. Also, having the highest corporate tax rates in the developed world invites companies to do everything they can to move earnings off shore.

Businesses are very dynamic. You can't use cherry picked numbers and static analysis. You could be right, but it is highly unlikely.