Source: https://www.mof.go.jp/english/pri/reference/ssc/historical/all.xls

Raise Japan’s corporate tax rate? Not so long ago, that would have been unthinkable. On the contrary, for the past few decades, Tokyo has steadily lowered the top rate on corporate income from 52% in 1994 to 30.6% at present (see chart below).

Source: National Tax Agency https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/corporate-tax-rate, OECD https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REVJPN

But the government did not get what it paid for: a hike in investment and wages. So, now, the notion of rolling back some of those cuts is being discussed internally by the Kishida administration, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Tax Commission, the Ministry of Finance (MOF), and even the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI). Previously, METI had been the biggest governmental booster of corporate tax cuts, so the mounting disillusionment is quite telling. The MOF, which tends not to like any tax cut, was never supportive but acquiesced in the past, partly in return for hikes in the consumption tax.

(Since I initially posted this, METI has come out firmly against a hike in the corporate tax, despite some dissent on this within the Ministry. This is based on a conversation with a senior official.)

While a corporate tax hike is now thinkable, it remains to be seen whether it is doable. Still, the fact that this option is even on the table is not only a big shift in governmental thinking but also a sign of the waning power of the big business lobby, Keidanren, on this issue. For a quarter of a century, Keidanren had successfully persuaded the government that, if taxes were lowered, Japanese companies would not only have the money and incentive to invest more, hike wages, and reduced offshoring, but that Japan could attract more foreign companies. As one previously-persuaded, but now chastened, official told me: Keidanren’s forecasts never panned out.

The Trigger Vs. The Cause

The immediate trigger for the rethink is the need to finance a doubling of defense spending from the longstanding limit of 1% of GDP to around 2% over the next five years. That amounts to about ¥5 trillion ($33 billion) each year in extra spending. The head of the LDP Tax Commission, Yoichi Miyazawa, told Nikkei that “If we expect a significant amount of revenue, then we need to consider a significantly large tax,” stressing that relying on bigger deficits would be “so irresponsible.” Miyazawa, it should be noted, is a cousin of current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, as well as a former MOF official, and a nephew of the late Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa.

Miyazawa stressed that (politically difficult) cuts in spending should come first, but, “If we are still short (of funds), we would have to tap tax revenue.” In a Reuters interview, he added, “I've heard various rumors about tax items, but I haven't made any suggestions...We must consider from scratch, including raising income [on more affluent individuals] and corporate taxes.”

Unfortunately, Miyazawa ruled out any hike in Japan’s extremely low carbon tax. It is possible but unlikely that Kishida will overrule him on this matter.

While defense spending is the trigger, the underlying factor is disappointment in the failure of past tax cuts to deliver promised results. At their November 26 meeting, members of Kishida’s New Capitalism Council were given materials illustrating the degree of failure. Between 2000 and 2020, the combined yearly profits of Japan’s 5,000 thousand largest corporations almost doubled (up ¥18 trillion or $120 billion), but their compensation to workers fell 0.4% and their capital investment fell 5.3%. Nor did the promise of more inward foreign direct investment pan out. So, raising the tax would be in line with Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s “New Capitalism” agenda. Back in May, an anonymous member of the LDP Tax Commission told Jiji Press, “While we won’t be able to drastically raise [the corporate tax], we need to implement a structural transformation that suits the current situation of Japan.”

Fallow Corporate Cash Follows Weak Shareholder Power

Let’s see how Japan’s mountain of retained earnings arose and how it’s linked to poor corporate governance. The MOF numbers in this post cover Japan’s 1 million incorporated firms, which employ about 35 million people, a bit more than half of Japan’s labor force.

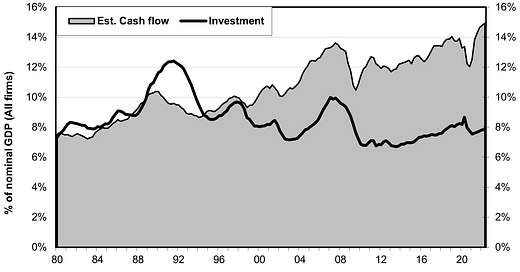

Current (recurring) corporate profits per year have more than doubled as a share of GDP from 7% in the early 1980s to 15% these days. A similar doubling has occurred in estimated cash flow (which equals half of current profits plus depreciation). However, companies are not plowing this cash back into the economy. Gross investment has stayed at 8% of GDP, the same level as in 1980. In recent years, the gap between cash flow and investment has amounted to about 6% of GDP (see chart at the top).

If Japan’s shareholders in listed companies had more power vis-à-vis management, they could force companies with few profitable investment opportunities to return the excess cash via dividends. In healthy capital markets, it is primarily rapidly-growing companies that pay either no dividends or relatively low ones. That’s because they can provide even greater returns to shareholders by using retained earnings to fund expansion. Later on, as companies mature and their growth slows, they return more of their profits to the shareholders. The latter can then invest in other, newer companies with better growth prospects, which increases national GDP. Or else, they can spend the money as consumers, which also promotes GDP growth. In Japan, even though the First Section of the Tokyo stock exchange is dominated by older, slower-growing companies, payout ratios remain small, despite having increased somewhat in the past couple of decades. The 2012‑2022 average was 36% of net income.

Imagine what could happen if Japan had more high-dividend stocks and more dividend-oriented mutual funds (investment trusts). In that case, more of the middle class could use the stock market as their piggy bank rather than, as at present, the bank accounts on which they earn negligible interest. Investing to gain dividend income is far less risky than gambling on the prospects for capital gains in a market with a four-decade history of sharp booms and busts. This dividend income would boost consumer spending. (While not all the excess cash is held by listed firms, the 5,000 biggest companies own two-thirds of the excess cash.)

Japan charges a 20% tax on both capital gains and dividends, a rate higher than the marginal rate on the 70% of Japanese households with an annual income under ¥6.95 million ($63,000 during 2017-21). Tokyo ought to consider a graduated rate on dividends so as to make them a better deal for the middle class, make them lower than the rate on capital gains, and to incentivize companies to pay out their excess profits.

Coming Up in Part II

If companies are neither investing their excess cash, nor raising wages, what are they doing with it? That will be detailed in Part II, as will the consequences of all this for national growth and the budget deficit, as well as a potential remedy.

Again you are doing a great job at highlighting the major issues with business in Japan. And again the powers that be in Japan fail to address the real issues!

It would be very dumb for Japan to increase corporate income tax. Part of the reason that money does not flow into Japan is that companies are no longer internationally competitive. It makes much more sense to lower the tax on corporate investments, dividend income and capital gains. You tax things you don't want -- if you don't want companies to grow... tax them more.

There are so many things that have to change in Japan to move the country forward. The bankruptcy code comes to top of mind. The large companies don't have good domestic competition because it is too risky to start a new firm. All the major pension funds are run by the government -- these entities are not focused on maximizing returns! They are more interested in the environment and social issues! They should be mainly focused on long run returns and governance - You can't produce long run returns without taking care of your employees. A company that overly damages the environment will not succeed either.

It is vital that the BOJ meet their inflation goals. Japan needs to have an increased focus on dividend income and this will not happen with zero inflation or deflation. Deflation has been the norm in Japan for three decades and it has killed the focus on income investing.

Japan is desperate for a much higher GINI coefficient! Without a group of "winners" there is a lack of inspiration for would be entrepreneurs of star business leaders. Top pay for top companies needs to be much higher. "Company first" people are great, but they focus on keeping a company's status quo more then trying to make them better.

Japan needs to focus on promoting business. They need to break the remains of life long employment and utilize human resources better (people need to be able to move to companies that can utilize their skills and not flounder at the same company for life).

Increasing pay and investment is the proper focus. Increasing taxes will never be an incentive to do this.

Higher corp tax rate won’t save Japanese government unless they levy on revenue instead of profit (income tax is based on household’s revenue, not profit, hehehe). Corp Japan’s margin is too narrow. Same for the inheritance tax rate... it has almost no impact on the total tax revenue but it is a show of the government that the rich suffers first.