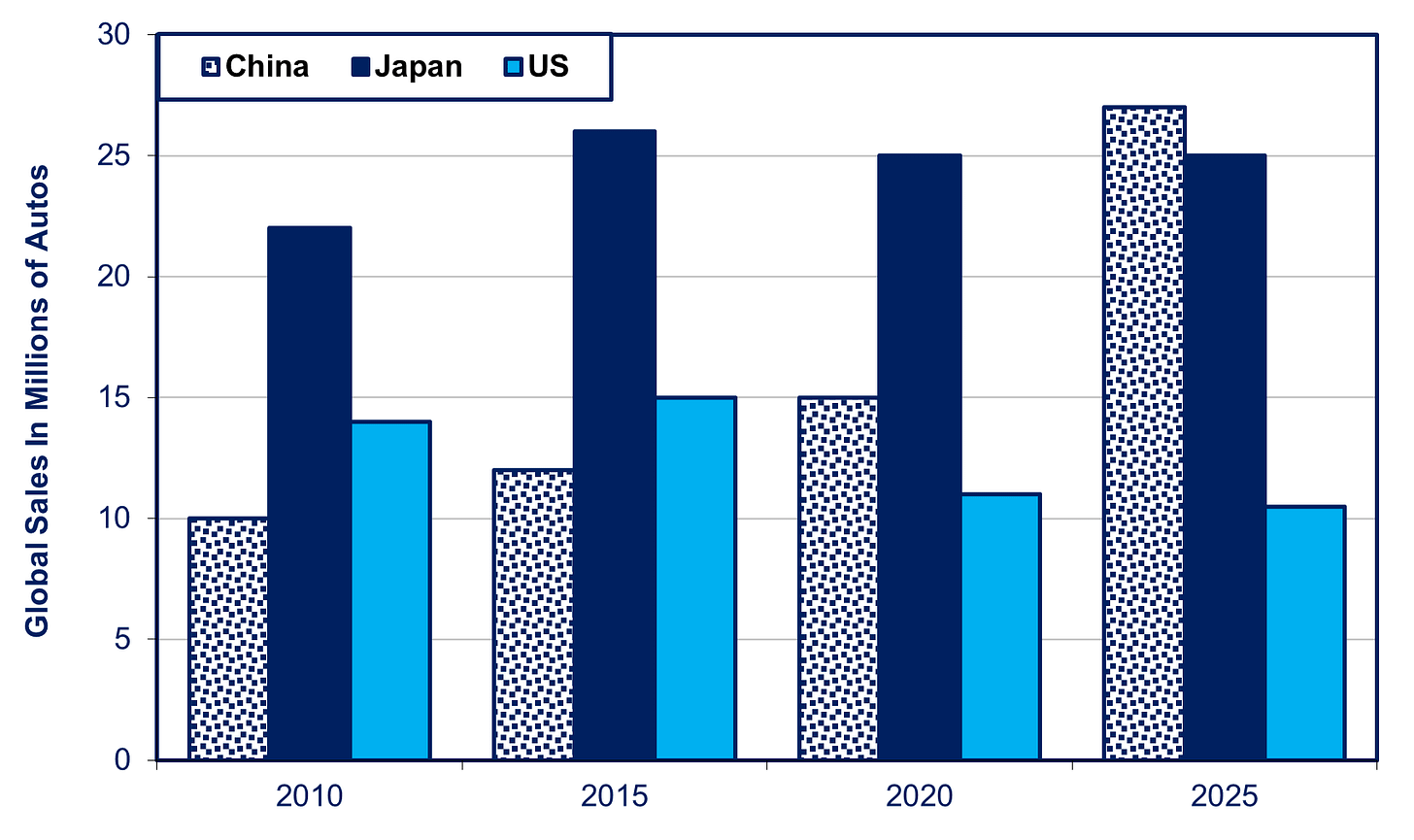

EV Revolution Helps China Replace Japan As Tops In Global Auto Sales

China’s Super Automakers And Its Zombies

Source: Nikkei at https://asia.nikkei.com/business/automobiles/china-auto-brands-to-top-2025-global-sales-overtaking-japanese-rivals

If you want to know why Japan was surpassed by China in 2025 as the world’s top seller of automobiles, consider willful blindness of Toyota Chairman Akio Toyoda. He says he cannot see a day when battery-electric cars (BEVs) surpass 30% of the market, no matter how much prices drop or technology improves.

In 2025, Japanese companies sold just 25 million autos globally, 5 million fewer than in 2018, slashing its share from 34% to 28%. Conversely, global sales by Chinese companies rose to 27 million, reaching a 30% share, according to the Nikkei analysis which used a common methodology for the US, Japan, and China (see chart above) Exports rose to 7 million, of which 37% were EVs. Japan’s exports languished at 4 million, with very few EVs.

(A reader questioned the 27 million number, pointing to a January announcement by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers that said production hit a much higher figure: 34 million. But this is a measure of how many vehicles were produced inside China in total, even if produced by foreign companies. Moreover, this figure does not include growing number of autos made by Chinese companies overseas, an amount predicted to rise to 2 million by 2027, the majority of them in Europe. Foreign-Chinese joint ventures (JVs) produce 31% of that 34 million, about 10 million, way down from a 64% share as recently as 2020. By contrast, to get an apples-to-apples comparison, the 27 million figure allocates a certain portion of that JV production to the foreign partner and the rest of the Chinese partner. It compares production/sales by the nationality of the companies, not the location of the production.)

The consequences of China’s rise for Japanese brands include hefty losses in market share and, in some cases, even declines in absolute numbers.

Japan Competing For a Shrinking Slice of the Chinese Auto Market

Within China, so-called New Energy Vehicles (NEVs), i.e., battery-operated EVs (BEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), now take up half of total light vehicle sales and in December reached 60% of passenger car sales. Conventional hybrids, on which Japanese companies have placed their bets, have a negligible share. Foreign brands still have a 67% share of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, but their share in the NEV segment is just 12%. Japanese companies have a 26% share of ICE vehicles but just 1% of the NEV segment. Given the rise of EVs, the foreign share of passenger car sales has plunged from 56% in 2017 to 31% in 2025. This leaves Japan struggling with other foreign brands over a shrinking slice of the Chinese pie.

Toyota’s 2025 sales in China were 1.78 million, down 9% from its peak of 1.94 million. Sales by Honda and Nissan have each suffered a catastrophic 60% plunge since 2020. Ironically, one reason Toyota has not done as bad as its compatriots is that it sells in China the BEVs that it disparages elsewhere, such as the $15,000 bZ3X. In 2027, it will open a factory to produce a BEV version of the Lexus.

Japan Automakers Losing to China In Their Former Asia Strongholds

Most of China’s auto exports, including EVs, go to middle-income countries. By contrast, Tesla and legacy automakers rely much more on expensive EVs aimed at affluent people in rich countries. The Ford EV pickup that it just abandoned at a great loss was priced at $70,000.

As a result, Japanese companies are struggling in countries where they used to be indomitable. In Thailand, the Japanese share has fallen from a stunning 80-90% to just 70%. In the ASEAN-6 countries (Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Singapore), the Japanese share fell from 70% in 2023 to 59% by the first half of 2025. During the same period, the Chinese share rose from 3% to 9%. In the first half of 2025, Honda sold 20% fewer autos in ASEAN’s biggest markets than the year before. Much of this is due to competition from Chinese brands.

One big factor is soaring market share for BEVs and PHEVs. By 2025, the EV share had reached 45% in Singapore, 38% in Vietnam, 21% in Thailand, and 15% in Indonesia. How can you succeed when you don’t even offer the product that customers increasingly wish to buy?

Was China’s Triumph Mainly Due to Unfair Government Aid

No one doubts that Chinese automakers produce quality products at affordable prices, but how are they seizing so much of the market? Some critics believe that China’s success relies on massive government subsidies that enable automakers to undercut foreign competitors by charging prices substantially below their real costs. This is the case in steel, but the situation in autos is more complex. This controversy reminds me of similar charges made in the 1970s-90s about Japan regarding steel, autos, TVs, semiconductors, etc., during the era of its dramatic rise. Some elements of the accusations were true, but if that was the whole story, Japan would not have posed such a challenge.

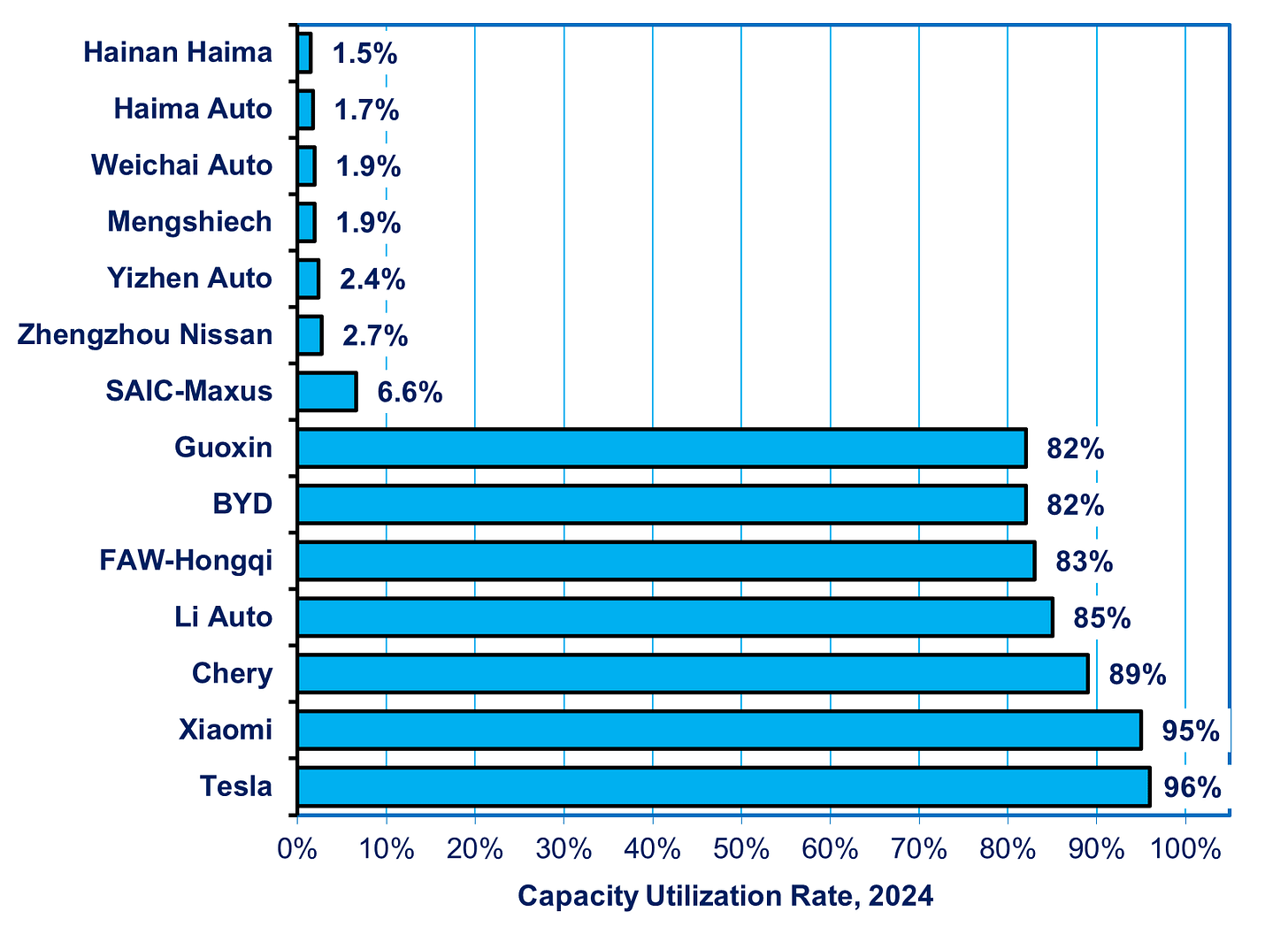

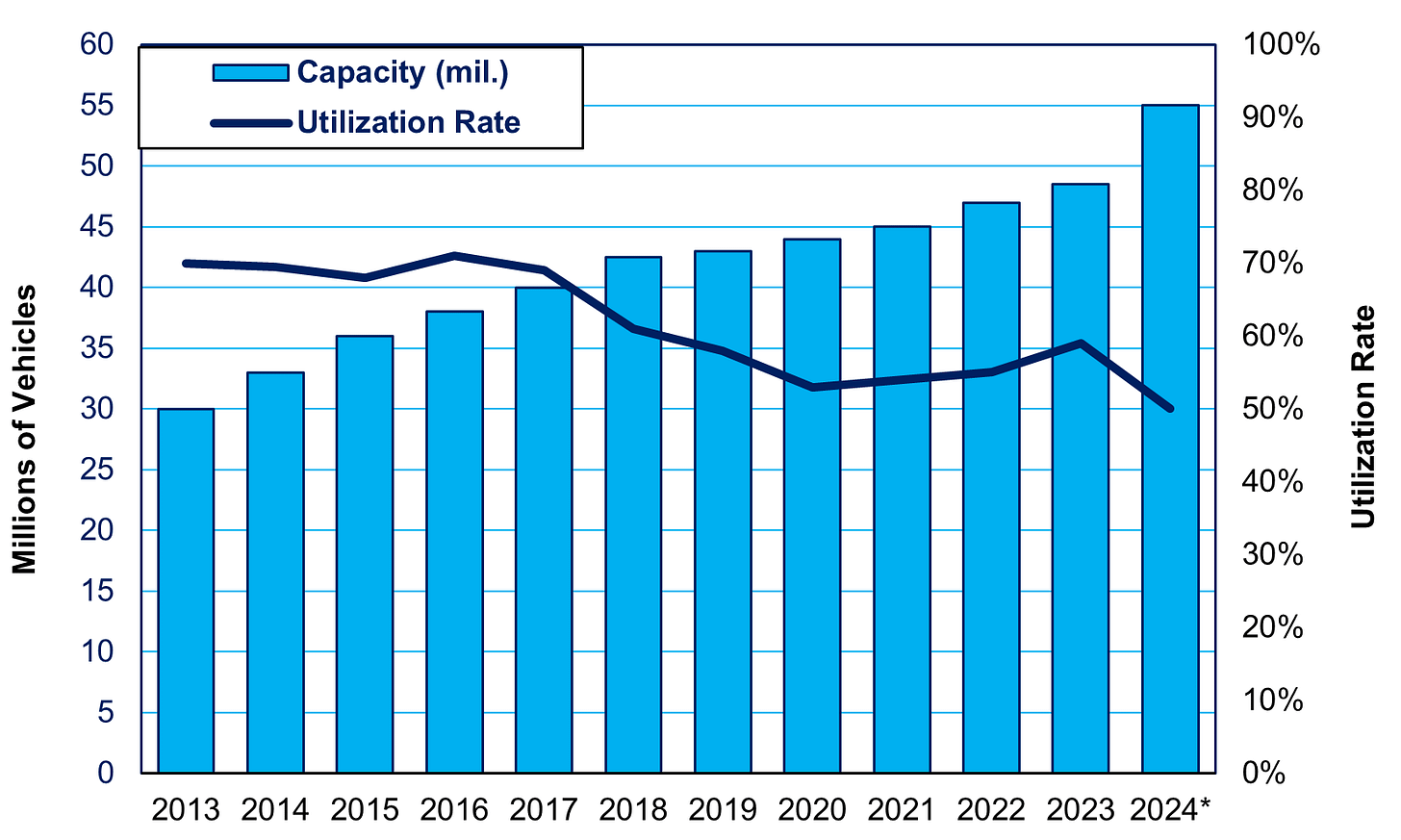

Here’s the picture I’ve been able to glean so far, one resembling Japan’s own “dual economy” of super-competitive companies and zombies. A dozen or so top Chinese automakers are spectacular in their technology, quality, market targeting, and so forth. While they once relied heavily on subsidies, that reliance is rapidly disappearing. On the other hand, a couple of hundred companies could not even still exist without excessive government aid. In a nation that can make twice as many cars as it can sell at home or abroad, many of them use only a few percent of their capacity. A 2023 study reported, “There are about 241 automobile manufacturers in China, of which about 20% are expected to produce less than 1,000 units in 2023, and about [another] 17% of them are expected to produce less than 10,000 units annually. On the other hand, nearly 15% of factories will have a capacity utilization rate of more than 95% in 2023, and their total output will account for 47% of [China’s] 2023 total output.” Some of the zombies are owned, in whole or in part, by national or local governments (see chart below).

National-Level Subsidies Are Shrinking

In looking at subsidies, we must distinguish between national-level overt subsidies and other subsidies, many of them local and hard to measure, e.g., underpriced land, continuous loans at sub-market interest rates, subsidies to other parts of the supply chain like mining and batteries, etc.

Scott Kennedy of CSIS has calculated that the BEV and PHEV auto segment received a total of $230 billion in various sorts of national-level overt subsidies during 2009-2023. In a classic “infant industry” policy, subsidies were initially high and then steadily reduced as the industry became more able to compete on its own. In 2023, subsidies totaled $4,700, less than the $7,500 price subsidy set by the Biden administration and not including its aid to charging infrastructure. The Chinese subsidy fell from 42% of total sales value in 2009-17 to 11% in 2023 (see table below), and it’s going to almost disappear. Industrial policy is not just about promoting an infant industry but also knowing when to stop.

This year, China removed the exemption of EVs from the 10% sales tax—which accounted for 87% of all subsidies in 2023—and put the tax on EVs to 5%. The tax rate will go to the normal 10% in 2028. Neither ICE autos nor conventional hybrids have received equivalent subsidies since Beijing began promoting EVs.

Source: https://www.csis.org/blogs/trustee-china-hand/chinese-ev-dilemma-subsidized-yet-striking

On the other hand, anecdotal evidence suggests that provinces and localities continue to provide vast subsidies to keep zombie automakers going.

In 2024, the EU contended that, without the subsidies, Chinese auto prices would be 45% higher and thus applied a 45% tariff. In any case, the EU and China just reached an agreement this month to replace the tariffs with minimum price agreements for each model. There is also talk of “voluntary” company-by-company caps on the number of cars sent to Europe. That would help European companies like VW that import cars from their Chinese factories.

High Prices For Some Exporters; Dumping Prices For Others

As with the subsidies, the price picture is bifurcated.

On the one hand, the top companies, especially those in the EV segment, charge up to twice as much in the export market as they charge at home. Profits earned abroad help cover losses at home, where a fierce price war is driven by enormous overcapacity. Beijing is trying to rein in the price war. Even in the ICE segment, where domestic overcapacity is the worst, Chinese exporters still charge much higher prices in overseas markets than at home.

This practice is not limited to Chinese companies. Volkswagen’s made-in-China ID.4 BEV SUV carries a 50% higher price in Europe than in China. For its comparable Seal U Comfort, BYD charges 93% more in Europe. Yet BYD can underprice VW: $42,000 vs. $46,000 in Europe and $22,000 vs. $31,000 in China and still make big profits in Europe, as can other leading Chinese companies.

On the other hand, zombies can sell excess cars to bulk buyers like Zcar, which exports them as “grey market” zero-mileage cars at cut-rate prices, with no warranties or after-use service. Reportedly, 80% of China’s export of 500,000 “used cars” in 2024 were such zero-usage cars. While they are often priced thousands of dollars lower than official exports of new cars, sources are unclear on whether they are being sold below production cost. In any case, Beijing recently began cracking down on these grey-market sales because they were hurting the reputation of Chinese autos.

A Coming Shakeout?

While Chinese automakers sell 30 million vehicles per year, they have the capacity to make 56 million. That’s not only almost twice Beijing’s sales goal, but also 60% of all global sales by all companies. S&P Mobility doubts China will ever use that capacity, saying that a decade from now, it will produce only around 35 million. Most of the excess lies in ICE autos that customers are abandoning. As in other sectors, Beijing has set in motion something it seems unable to control. The wasted money put into these factories is dragging down GDP growth.

Of the 129 companies now making EVs, consulting firm AlixPartners predicts that only 15 will remain in 2030. In 2025, the top ten companies dominated the domestic EV market with a 95% share, up from 60-70% just a few years ago.

It is not unusual for an economy to spawn a huge number of companies when a product is new and then experience a shakeout. Each new company is an experiment, and no one can foretell which strategy or technology will succeed. In the US, 1,300 automakers rose and died between 1895 and the early 1930s, some of them running on wood, steam, gasoline, or even batteries. Much the same occurred in the dot.com bubble. Just as it is necessary to give free rein to all these experiments, it is essential to let those who cannot pass muster die. Will China’s central, provincial, and local governments allow the necessary shakeout and capacity reduction?

The good news is that at least some companies are being allowed to die, albeit too slowly. The majority of the 500 EV startups in 2018 no longer exist.

The bad news is that, despite talk of capacity reductions, as of 2025, governments and companies have kept adding even more wasteful capacity, and the industry-wide capacity utilization rate has halved (see chart below). The size of the excess shows that something has gone seriously wrong. Once the national government made EVs a national priority, each province, and even localities, competed to create their own auto majors to create jobs and tax revenue from sales of land. It parallels the real estate boom. This is the kind of spree that drags down growth.

Source: https://www.just-auto.com/analyst-comment/the-polarisation-of-chinas-automobile-production-capacity/ Note: 2024 numbers are from press sources and may use a method inconsistent with the previous years.

In the words of Dickens, they are the best of companies; they are the worst of companies.

Paid subscribers will be eligible for my new mini-posts (see this for more info). Beyond that, if you feel you’ve gained insight from this blog, ever restacked it, if you ever subscribed to my previous publication, The Oriental Economist Report, and certainly, if you or your firm have gained insights that helped guide your investments, please support the blog with a subscription or by “buying me a cup of coffee.” You can buy a cup or two on a one-time basis, or once a year, or once a month.

Thank you for your wonderful newsletter. A small correction below:

Unlike the Chinese OEMs, Japanese vehicle assembly is highly localized (e.g. millions of Japanese vehicles are produced each year in US, India, thailand, etc) accounting for perhaps more than half of total production. Indeed this is one of their sources of competitive advantage. The number of vehicles exported from Japan is therefore not a reliable indicator of much at all. (Chinese OEM production localization is happening also but still limited compared to the Japanese. )

Therefore when comparing production levels of different countries car companies, this must be taken into account in order to avoid materially wrong conclusions and also to avoid embarrassing yourself unnecessarily.

Akio Toyoda is such a symbol of this generation of dummies incapable of doing basic physics or even sums to see that their bet on hydrogen was doomed. Putting lawyers/MBAs at the helm where engineering decisions are vital --> same results in the U.S. (Boeing) or Japan (Toyota).