Overview

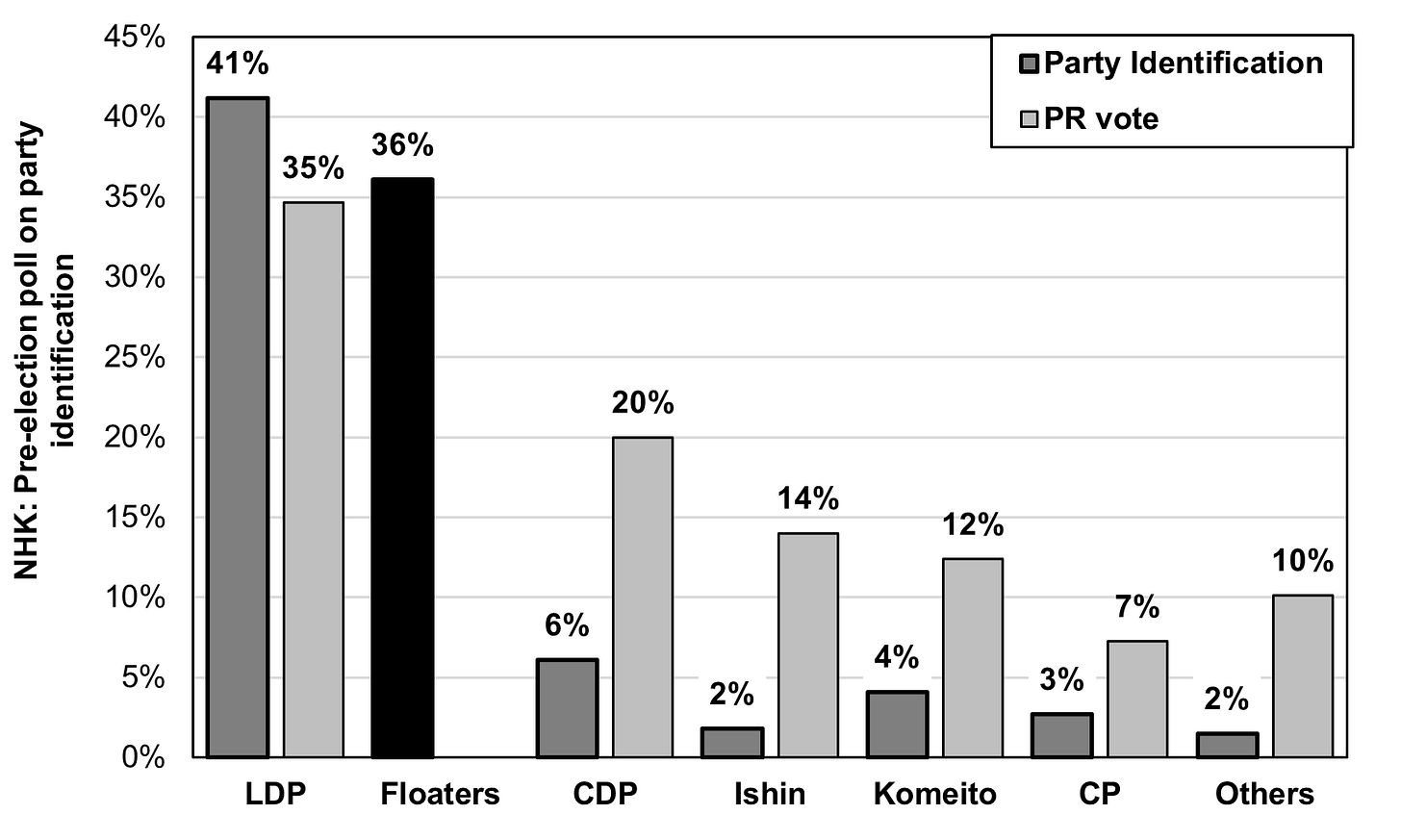

As we noted in our post two days ago, the majority of Japan’s “floating voters”—the 36% who are not loyal to any particular party—stayed home during Sunday’s election. Only 15% of those who did vote said they were floating voters. But what about that 15%? How did they vote?

The turnout rate and preferences of floating voters are pivotal if the main opposition party, the center-left Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) is to have any future viability. Only 6% of voters consider themselves CDP supporters. Yet, in the PR segment of the ballot, 20% of all votes went to the CDP.

The floating voters are also pivotal to the future of the rightist Ishin (Innovation) Party’s ability to expand beyond its regional base in Osaka. While just 2% of all voters regarded themselves as Ishin supporters, it garnered 12% of the PR vote.

The fact is that no party other than the LDP has loyalists in the double-digits, and the floaters are almost as big as the LDP.

Fortunately, Tokyo University professor Kenneth Mori McElwain analyzed how the floaters voted at the post-election Zoominar hosted by Ulrike Schaede. While the details can cause the eyes to glaze over, what emerges is a picture of disenchantment with the major parties. In the Proportional Representation (PR) segment of the ballot—in which voters select a party, not an individual candidate—34% of the floaters selected a party other than the top four. That’s way up from 21% in 2017.

Going Deeper Into the Weeds

To analyze the vote, we are forced to keep two complications in mind:

1) Of the 465 members of the Lower House, 176 are chosen via the PR segment. The other 289 are chosen in Single Member Districts (SMD), in which voters select an individual. For reasons detailed below, floating voters often for a candidate of one party in the SMD segment but choose another party in the PR segment.

2) There has been a somewhat confusing series of party realignments over the past few years. This is important for understanding the 2021 behavior of floating voters. In the 2017 election, there existed an important, but short-lived, party that no longer remained in 2021. It was called the Party Of Hope and was led by then-Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike. It regarded itself as a center-right party although some of its leaders, including Koike, were very nationalistic. In 2018, it merged with some other center-right Diet members to form the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP). Then, in 2020, the new DPFP merged with the center-left CDP. More than a dozen of the more conservative members refused to merge and kept the name DPFP.

With this in mind, we’re ready to look at how the floaters voted this year compared to 2017.

First, let’s look at the SMD segment, seen in the chart above. In these districts, 13% of the floating voters selected a CDP candidate in 2017, a number that soared to 41% in 2021. Where did those votes come from? Mainly, it seems, from the 26% of floating voters who had chosen a Party of Hope candidate in 2017 (13% plus 26% equals 39%). In other words, regardless of all of splits and mergers and further splits and mergers, those floating voters who turned out remained loyal to the same individual Diet member regardless of that person’s party label. (The speculation in this and the following paragraphs is my own, not McElwain’s.)

(Note: McElwain’s data doesn’t cover all 289 SMDs, just the 217 of them where the CDP coordinated with a couple tiny center-left parties as well as the Communist Party.)

In the PR segment, however, the same floaters voted very differently. While these floaters remained loyal to an individual Diet member in the SMD segment—even when that member switched parties—they have no loyalty to any party. That’s what makes them floaters. What the data shows is tremendous disenchantment and fragmentation.

As we can see in the chart above, the LDP share dipped only a couple percentage points. On the other hand, the CDP share of the floaters’ vote fell by 8 percentage points from 29% in 2017 to 21% this year. The difference seems largely accounted for by the 8% who voted for the DPFP in the PR segment this year (the DPFP didn’t exist in 2017). Had the DPFP not refused the merger, the CDP would have done much better. This is part of the fragmentation of the non-LDP field.

Most interesting is the fragmentation of the 20% who had voted for the Party of Hope in 2017. Where did their votes go? The data seems to indicated that perhaps half went to Ishin, whose vote share among the floaters doubled from 9% to 18%. Ishin did well, not just in its home region around Osaka, but also fairly well in the PR blocs around Tokyo, the regional base of the Party of Hope.

Even though Ishin is a rightist party that combines nationalism, populism, and neoliberal economics, it gained credibility from its handling of COVID in Osaka as well as the personal chemistry of its leader, the mayor of Osaka. McElwain commented that, in this election, “Ishin may have successfully positioned itself as a viable or ‘realistic’ centrist alternative to the LDP on the right and the CDP-Japanese Communist Party [alliance] on the left, leaving aside the question of whether they are, in fact, centrist.”

What about the other half of floaters who had voted for the Party of Hope in 2017? That appears to have gone to a variety of minor parties.

In fact, 34% of the entire independent vote went to the minor parties this year, way up from just 21% in 2017.

Bottom Line

The bottom line is a great disenchantment among floating voters. Not only did less than half of them bother to come to the polls, but, those who bothered to vote turned away from the leading parties. It remains to be seen whether that portends the continued ability of the LDP to rule with a minority of the vote or some further realignment that eventually turns the LDP out of power again. The future of the center-left also remains uncertain. As the Japanese expression goes: in politics, six inches ahead lies darkness.