Can Korea Teach Japan How to Grow Again?

How Korea Outstripped Japan in Per Capita GDP Despite Sharing So Many Structural Defects

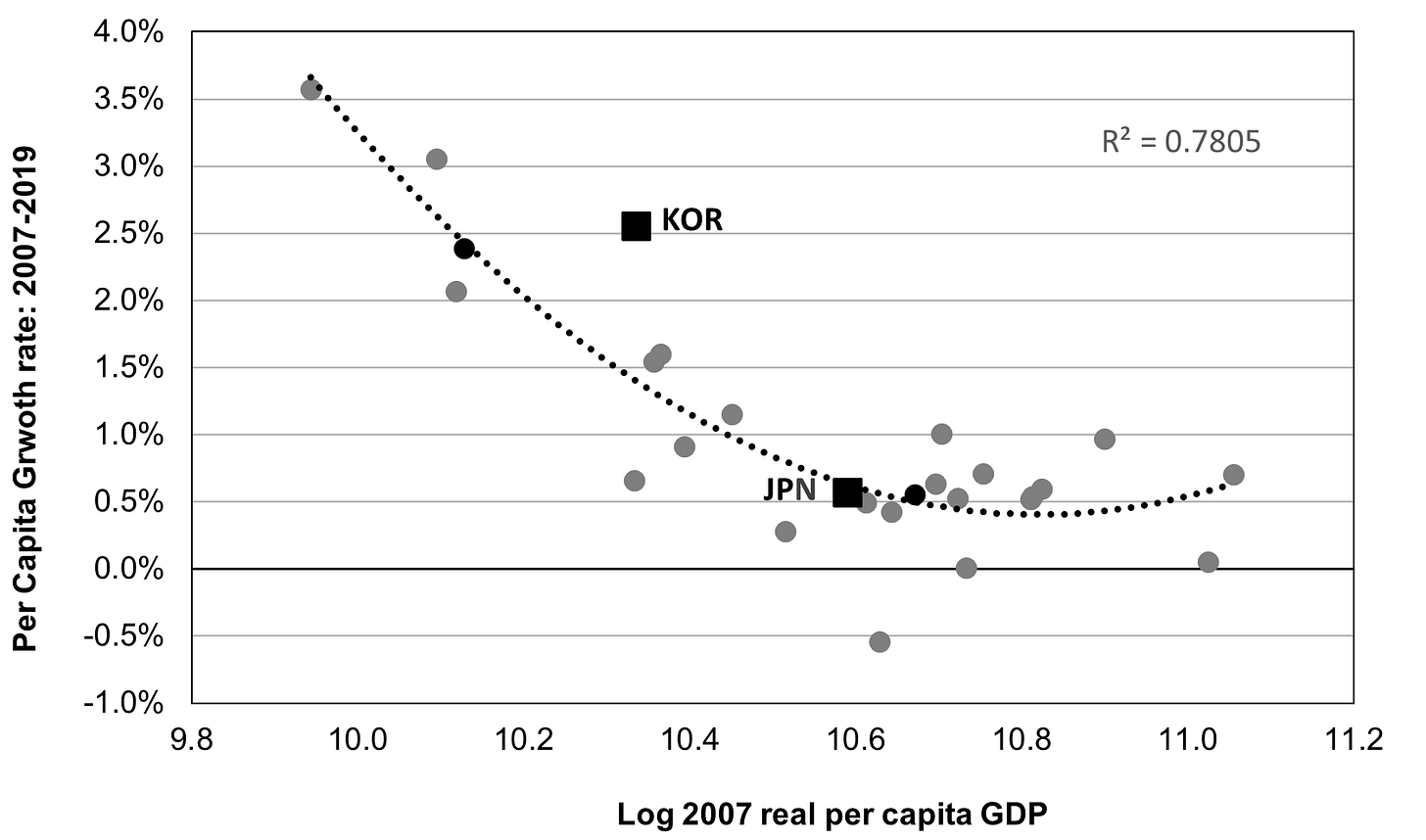

It’s a mystery. How did Korea surpass Japan in real per capita GDP—as shown in the chart below and detailed in a previous post—despite suffering from many of the same structural defects?

In fact, Korea resembles Japan so much that many experts have warned, in the words of the Washington-based Korea Economic Institute in 2015, that without enough reform, “We only need to look to Japan to see Korea’s likely future.” And yet, Korea has not only passed Japan, but is growing much faster than other countries at its level of development, as seen in the top chart (growth tends to slow down as countries become richer).

Precisely because Korea is both similar to, and different from, Japan, it’s a good mirror for Japan to see possible solutions to its own problems. Like Japan, Korea is a “dual economy,” i.e., a hybrid of extremely efficient exporting sectors and woefully inefficient sectors in parts of domestic manufacturing and most services. In addition, the productivity gap between Korea’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and its large firms is the third worst in the OECD. The economy is so lopsided that Samsung Electronics alone accounted for an astonishing 20% of all Korean exports in 2019, a very risky situation. Meanwhile, more than a third of its labor force consists of low-paid non regular workers and wage inequality is worse than in Japan. As a result, while Korea is doing very well compared to others, the OECD says its defects lower its growth rate by 1-2 percentage points below what it could be.

What distinguishes Korea from Japan is that it has gotten more of the “basics” right and it has made more serious efforts to address its defects.

To grow well over the long haul, countries need stability in macroeconomic demand to make them more resilient in the face of economic shocks, from global financial storms to COVID to Russia’s war. Workers’ wages have to rise in tandem with overall GDP so that households can afford to buy what they make. That eliminates the need for chronic government deficit spending and an ever-larger trade surplus to make up for shortfalls in private domestic demand, as in Japan. From 1990 through 2020, the average Japanese worker enjoyed virtually no increase in annual real wages, whereas the pay of Korean workers doubled, and the latter now enjoy higher real wages than their Japanese counterparts. Moreover, Seoul has raised the minimum wage to 62% of the median wage, the third highest ratio in the OECD. By contrast, in Japan, it’s only 45%.

As a result, Korea is far less vulnerable to global shocks, even though Korea’s trade:GDP ratio is twice as Japan’s. During the 2008-09 financial meltdown, Korea’s GDP rose by 4% even as Japan’s fell 7%. During the first two years of COVID, Korea’s GDP rose 3% while Japan’s fell 3.0%. Countries less vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks enjoy faster average growth over the long term. (While Japan looks in the top chart to be in the middle of the pack, “unhappy countries,” to paraphrase Tolstoy, are unhappy for different reasons. In the case of Europe, the problem was a self-destructive austerity campaign in reaction to the 2008‑09 global financial maelstrom and the consequent debt crisis.)

The main resource of both Japan and Korea is the skills of its labor force. Yet, Korea has built up those skills much more so than Japan. “Human capital” is measured not just by how much schooling each person gets but also how effectively that education and training contribute to growth. In 1960, Korea enjoyed only 70% as much human capital as Japan. By 2019, it had 5% more. Korea came in 5th among 31 rich countries while Japan came in 13th. Spending by Japanese companies on off-the-job training has dropped 40% since 1991.

Among rich countries, much of growth comes from consistently upgrading to the most modern technology, e.g., steel mills with electric arc furnaces. Since all rich countries have access to the same technology, one of main reasons rich countries differ in growth is how well they use that technology. Both Korea and Japan suffer from a big digital divide between the corporate giants and the SMEs. Still, those Korean companies who do invest in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) have done better job in exploiting its possibilities. The Institute for Management Development ranks countries on that sort of “business agility” in the digital area. Out of 64 countries in 2021, Korea came in 5th whereas Japan lagged at a dismal 53rd. When the World Economic Forum ranked 141 countries according to the digital skills of its labor force, Korea came in 25th but Japan a surprisingly low 58th.

Both countries talk about encouraging more entrepreneurship and helping SMEs grow. Korea, however, is turning more of its rhetoric into action. Investing in R&D makes a big difference in how many high-growth SMEs a country generates. In Japan, only 12% of government financial aid to R&D goes to companies with less than 250 employees, the least in the OECD. By contrast, half goes to SMEs in Korea. That’s one reason that 22% of all Korean business R&D is conducted by SMEs, more than either the US or France.

While all of this may look like a bad news story for Japan, there is a big silver lining in that grey cloud. Korea’s experience shows that, if Japan implements the right structural reforms, it too can have a bright future.

Toyo Keizai just published an expanded version of this story at https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/536058 in Japanese and https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/537393 in English.

Brilliant analysis!

I don't agree with saying that South Korea is all concentrated in Seoul. In fact, for example, cities like Ulsan have a higher GDP per capita than Seoul, which is not the case in Japan, where Tokyo has a much higher GDP per capita than the rest of the country. And in fact it should be just the other way around, being larger in population is an advantage in terms of economies of scale and by the way in Japan a higher proportion of people live in big cities than in South Korea. If Japan is not growing it is because it has adopted bad policies and decisions, not because of geographic, demographic or cultural reasons.