How To Restore Japan As A Startup Nation

Will Kishida Offer The Measures Needed To Turn Rhetoric Into Reality?

“It is therefore my earnest wish to create the next startup boom in Japan,” Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced in his May 5 London speech. Past Prime Ministers have also offered lofty goals, but not the measures needed to turn their rhetoric into reality. Here are some policy proposals that will let us judge whether Kishida will prove to be different. Before getting to them, let’s see why this is so important, and why Japan lags.

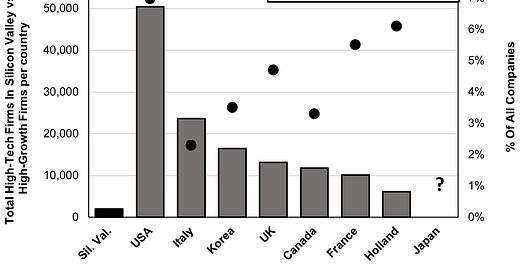

When people hear the word “startup” or “entrepreneur,” the image that often comes to minds is a high-tech, Venture Capital (VC)-financed enterprise in Silicon Valley. But there are just 2,000 high-tech firms in Silicon Valley. By contrast, in any year, according to OECD statistics, America is home to more than 50,000 high growth enterprises, i.e., those with at least ten employees and which grow at least 20% per year for three years in a row. The comparable number in Korea is 16,000; 13,000 in the UK, and 10,000 in France. Only a small fraction is in high-tech, and few get VC money. Since Japan does not measure how many it has, Tokyo’s startup policy is flying blind.

The continuous creation of high-growth small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is indispensable to growth in living standards. During the 1980s-90s in the US, a stunning 60% of the growth in factory output per worker came from the entry of firms less than five years old and the closing of less efficient older firms. That’s because new firms come up with fresh ideas and often force the corporate giants to up their game. Consider how Tesla’s success has compelled the auto giants to move more quickly to electric vehicles.

Unfortunately, Japan has too few high-growth SMEs, and that’s one reason real (price adjusted) family income has been stagnant since 1995. Among all OECD countries Japan’s SMEs suffer the slowest growth in their first ten years. The biggest hurdle is that ambitious young firms can’t get the financing they need to expand. Their growth is also hampered by issues related to two other problems that Kishida mentioned: technology and human capital.

Kishida Needs A Broader Vision

Regrettably, when Kishida talks of startups, it seems that he, too, may be excessively mesmerized by the glamour of VC-financed companies. For example, an LDP group created to push for Kishida’s program—named the Startup Parliamentary League —called for a tenfold increase in VC investment in to ¥10 trillion ($77 billion) by 2027. That would be terrific, but VC-funded enterprises should not be the sole focus. It’s therefore encouraging that League chieftain Takuya Hirai, the former Digitization Minister, told Pensions & Investments that Japan also needs increased tax breaks for “angel” investors. In 2019, angels in the US invested $24 billion in 64,000 companies, an average of $376,000 per company. That’s 20 times the number of superstars who received VC money.

In other countries, well-designed tax incentives have created a boom in angel investment, but Japan’s tax break is tiny: a maximum tax deduction of ¥8 million ($62,000) for an angel’s total investment in all companies. In the UK, by contrast, angels can deduct 30% of their investments up to £1 million ($1.25 million) and twice as much for “knowledge-intensive” companies. Despite efforts by METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry) to raise the ceiling, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) only agreed to add some benefits for the 3-to-10-year-old startups. This is shortsighted since more startups means more tax revenue. Will Kishida overcome MOF resistance?

Kishida may also be chasing glamour when it comes to technology. He proposed a “national strategy” in five areas, the first of which is Artificial Intelligence (AI). This is akin to proposals in the past that imagined superconductors or nanotechnology as magic bullets for growth. This seems a misguided priority when Japanese companies are not even using existing technologies well, partly due to insufficient human capital.

Out of 64 countries, IMD rated Japan 62nd in the digital skills of its population. One reason is that, among 80 countries, Japan’s schools come in dead last in teachers’ knowledge of digital technologies and their ability to teach it, and in resources to aid these teachers. Since these skills are not included in university entrance exams, teachers see no reason to teach them. In 2025, digital questions will be added to the exams, but who will teach the teachers? This is the kind of issue Kishida should prioritize when he says, “Investment in human capital is at the heart of the growth strategy.”

Measures To Overcome The Financing Gap

New companies have trouble finding customers. So, as Hirai noted, it would help if they could sell to the national and local governments, whose purchases of goods and services amount to 16% of GDP. In 2015, the government created a “set aside” that gave preferential treatment to companies under ten years old. However, the amount of procurement is trivial, in 2021 only ¥77 billion ($592 million), a negligible 0.8% of total national government procurement. A truly sizeable “set aside” would not only give startups more revenue, but also help them more sales to private firms and also get loans from banks who now lend very little to young companies, especially those founded by women.

Research and Development (R&D) is critical to growth among startups, but in Japan only 8% of financial aid goes to companies with fewer than 250 employees--the lowest share in the OECD. The reason is that all of Japan’s aid comes via a tax credit, and such credits can only be used by companies already earning profits. Startups takes years to become profitable. Other countries solve this dilemma with a “carry-over.” That means, if a company earns a tax credit but is not yet profitable, it can use that credit years later when it finally earns profits. In the UK, the carry-over is forever. In the US and Canada, it's 20 years. In Japan, it was a useless one year, until even that was eliminated by the Abe administration.

The Kishida team wants the enormous Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) to invest more in VC funding. That would help a great deal, as long as the GPIF does not invest on its own but rather through independent VC funds, foreign or domestic, and not via corporate VCs.

This is an abridged version of a Toyo Keizai article, available at https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/592735 in English and https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/591483 in Japanese.

Hi Richard

I always enjoy reading your thoughtful articles. Reading your book at the moment.

I strongly agree there is so much more the government can do to support more entrepreneurial activity in Japan. Question - how do you square this with the incredible startup activity in the restaurant industry in Japan. I don’t have data to support this but anecdotally I’ve met many salarymen who leave their corporate posts to start a little restaurant. Japan is clearly world class in this space. Why not in tech/bio etc? Perhaps the capital required is so much less than a new software business.

My view is - and you make this point in your book - the Japanese clearly have it in them to start new enterprises. Thank you

Thank you Richard! I learnt a lot from your articles!!