Inflation: Japan Stands Alone, Part II

Kuroda’s Dilemma on Interest Rates and the Yen

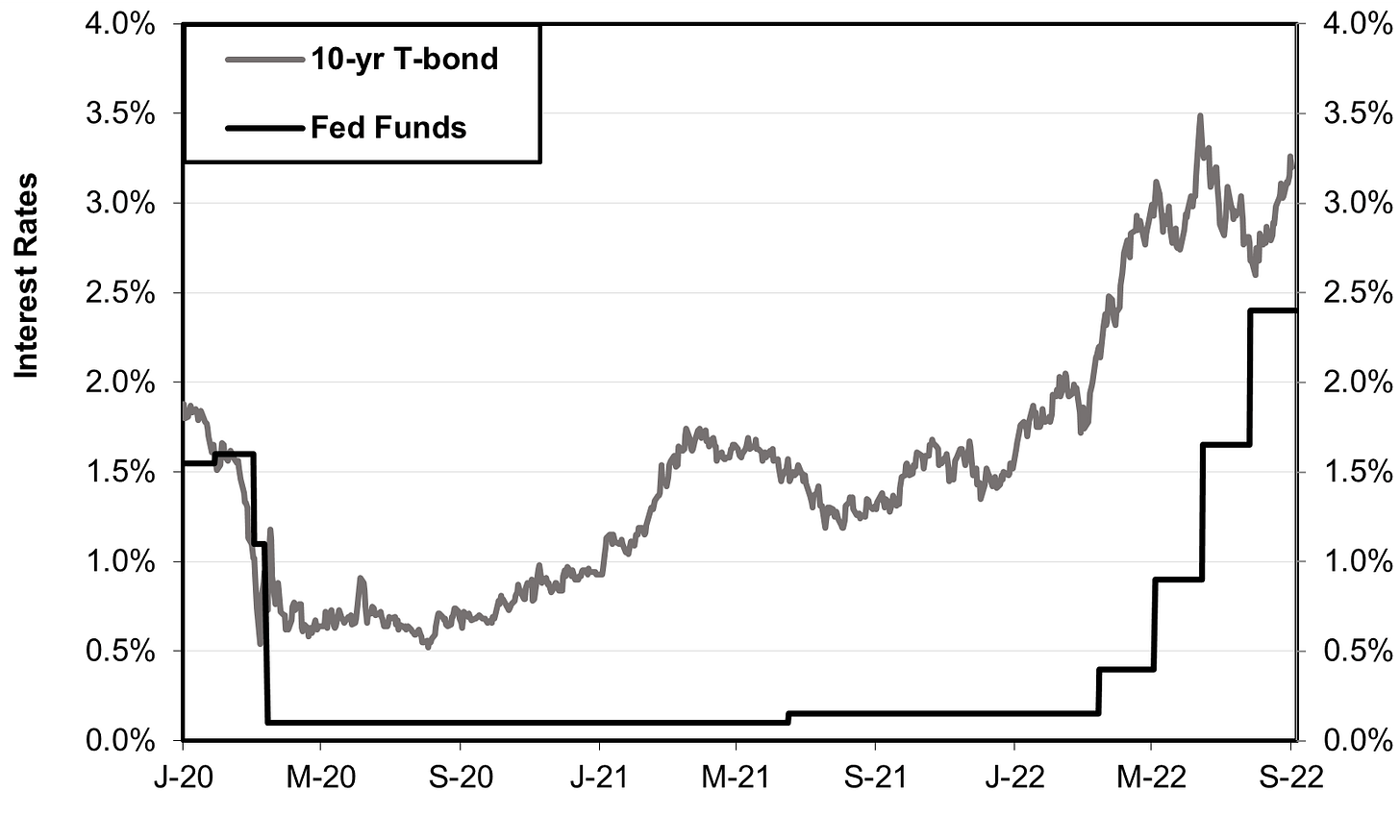

Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda faces a big dilemma. If domestic demand and inflation were the only considerations, his policy of keeping interest rates at near-zero levels would seem to make perfect sense. However, the side-effect is a steep plunge in the yen’s value. That is a direct result of the growing gap between interest rates in Japan and those in the US and Europe (see chart below). Kuroda asserts there is no dilemma, based on his claim that a yen this weak is still a net benefit for Japan’s economy because it stimulates more experts. But many economists say the costs are greater than the benefits. It is certainly causing more harm than good to Japanese households while forcing the government to hike deficit spending to make up for the loss of consumer purchasing power. Moreover, the boost to exports from a weaker yen is not as powerful as it used to be.

To begin, let’s briefly review the key points in Part I of this post. Japan’s inflation is very different from that in the US and Europe. Not only is Japan’s inflation rate far lower—just 2.4% headline inflation and 0.4% core inflation—but 88% of it comes from the food and energy sectors that are heavily influenced by global factors beyond the control of the BOJ. Moreover, compared to the US and Europe, most of Japan’s inflation is due to “cost-push” forces rather than “demand-pull.” The latter refers to the excess demand which prevails in the US and to a large extent in Europe. When inflation is a case of demand-pull, the clear solution to demand-pull inflation is for the central bank to reduce excess demand via higher interest rates. By contrast, the supply problems causing cost-push inflation—from rising energy prices to a shortage of semiconductors—can simultaneously raise prices and hamper GDP growth, a phenomenon sometimes called “stagflation.” That’s a far more thorny problem for a central bank to tackle.

Kuroda argues that the cost-push factors behind Japan’s still-low inflation are temporary. Indeed, the BOJ predicts inflation next year will be lower than this year, at 1.2-to-1.5%. Therefore, says Kuroda, Japan has no reason to raise interest rates; on the contrary, doing so would undermine both GDP growth and the BOJ’s effort to attain healthy demand-led 2.0% inflation.

The predicament is that Japan is not an island sheltered from outside financial storms. As other countries raise rates and Japan refuses, the result is a mounting gap between interest rates in Japan and those elsewhere. In response, investors shift money from Japan to the US and Europe, and the yen plunges to levels not seen since the financial cataclysm of 1998 (see chart).

Weak Domestic Demand and A Very Weak Yen

By raising prices for essential import-intensive consumer items, like food and energy, a weak yen leaves consumers and domestically-oriented businesses with less money to buy other items, like those produced at home. Paying more for imports transfers income from Japanese consumers to foreign producers as well as to Japan’s multinationals, who make more profits on their exports and foreign assets when the yen is weak. The yen’s price-adjusted purchasing power on the international market for goods and services is the lowest it has been since 1971. It is one of the reasons that consumer spending has been stagnant for the past nine years and, with the additional factors of two hikes in the consumption tax, Covid, and war in Ukraine, is now 4% lower than it averaged nine years ago in 2013 (see chart at the top).

It’s not just consumer demand that’s weak. Business investment is already down 9% from its 2019 peak, and higher interest rates would add to the headwinds. Moreover, while the official unemployment rate in July was just 2.5%, an additional 3.7% of the labor force was listed as “employed person [but] not at work,” i.e., employees with no tasks who are kept on the payroll with the help of government subsidies.

So, it’s quite understandable why Kuroda opposes raising interest rates when private domestic demand is so weak and domestically-created inflation remains so low. However, the cost of this policy could be a continued nosedive of the yen, which will further weaken private domestic demand. Currency traders keep going back and forth on the trajectory of the yen based on their estimates of future US inflation and Federal Reserve policy.

Will Speculators Defeat Kuroda?

Because of the tumbling yen, many financial traders believe Kuroda will be forced to let 10-year bond rates rise above 0.25%. Back in June, the BOJ had to spend an unprecedented $80 billion in just one week to defend the 0.25% rate, and there will no doubt be further attempts to force the BOJ’s hand. However, that makes the BOJ even more determined. It worries that, if the markets breach its 0.25% line in the sand, where will it stop? The smart money points out that, for the past 25 years, those who’ve bet against the BOJ’s ability to control interest rates have repeatedly lost truckfuls of money. Those betting against the BOJ retort: past results are no guarantee of future outcomes.

The good news for Kuroda is that, even though the Fed is raising overnight rates, called Fed funds, such hikes do not move 10-year bond rates to the same degree. That’s because the hike in the Fed Funds is only temporary. In fact, when investors fear that a recession will result from the Fed’s attempt to cool an overheating economy, the market typically goes into a so-called “inversion” in anticipation. That’s a case where the interest rate on 10-year bonds is lower than overnight rates (see chart below).

Notice in the chart below that today’s 10-year bond rate is actually lower than it was in June, even though the Fed funds rate has been hiked from 1.65% to 2.4%. So, it remains to be seen where the 10-year rate will go when the Fed raises overnight rates yet again at its September 20-21 meeting and if, as expected, continues to raise them at subsequent meetings.

Fasten your seat belts; it’s going to be a bumpy ride, with enough back and forth in the mood of the market to cause whiplash.

Isn't the issue with the yen more about Japan's lack of productivity growth (both services and goods). If the economy had real potential we would see money coming in to take advantage of the fall in cost to buy Japanese assets. The fact that Japanese companies are not very efficiently run (from a financial perspective -- no debt on the b/s -- piles of cash on the b/s...) and don't produce above market returns keeps buyers away even at the lower prices. I don't have access to an ROE figure for the TOPIX, but I'm guessing it is still quite low...

Japan also has very poor demographics. There sill is no immigration and a birth rate the assures the country of a shrinking population.

I think any short term pain associated with food and energy prices is a reasonable price to pay for the decades of decay that needs to be reversed. Japan needs to rebuild/restart all the nuclear plants. They need to face the music and use one frequency (60 Hz) across the entire country. They need to focus on growing larger quantities of food and not having tiny "high quality" producers -- it is crazy that you can't sell a cucumber in Japan if it is too curved! I don't recall seeing a single large scale farm in my years living in and visiting Japan.

I couldn’t find the chart referenced by the line referring to 1998 cataclysm