Japan and Climate, Not As Bad As It Looks, Part II

We Have Japan To Thank for Solar Energy and Electric Vehicles

Source: https://nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/owid-public/data/co2/owid-co2-data.xlsx Note: Kilograms per kilowatt-hour of primary energy consumption

In 2010, the year before the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan’s energy and climate future looked encouraging. The country had some of the cleanest energy among advanced countries. Decades before people heard about global warming, Japan was pioneering solar power and electric vehicles—albeit for other reasons. Without Japan’s efforts, the world today would have far less potent technological weapons to defeat climate change. Understanding the pre-Fukushima situation is necessary for us to understand today’s policy battle.

The Revolutionary 2010 Strategic Energy Plan

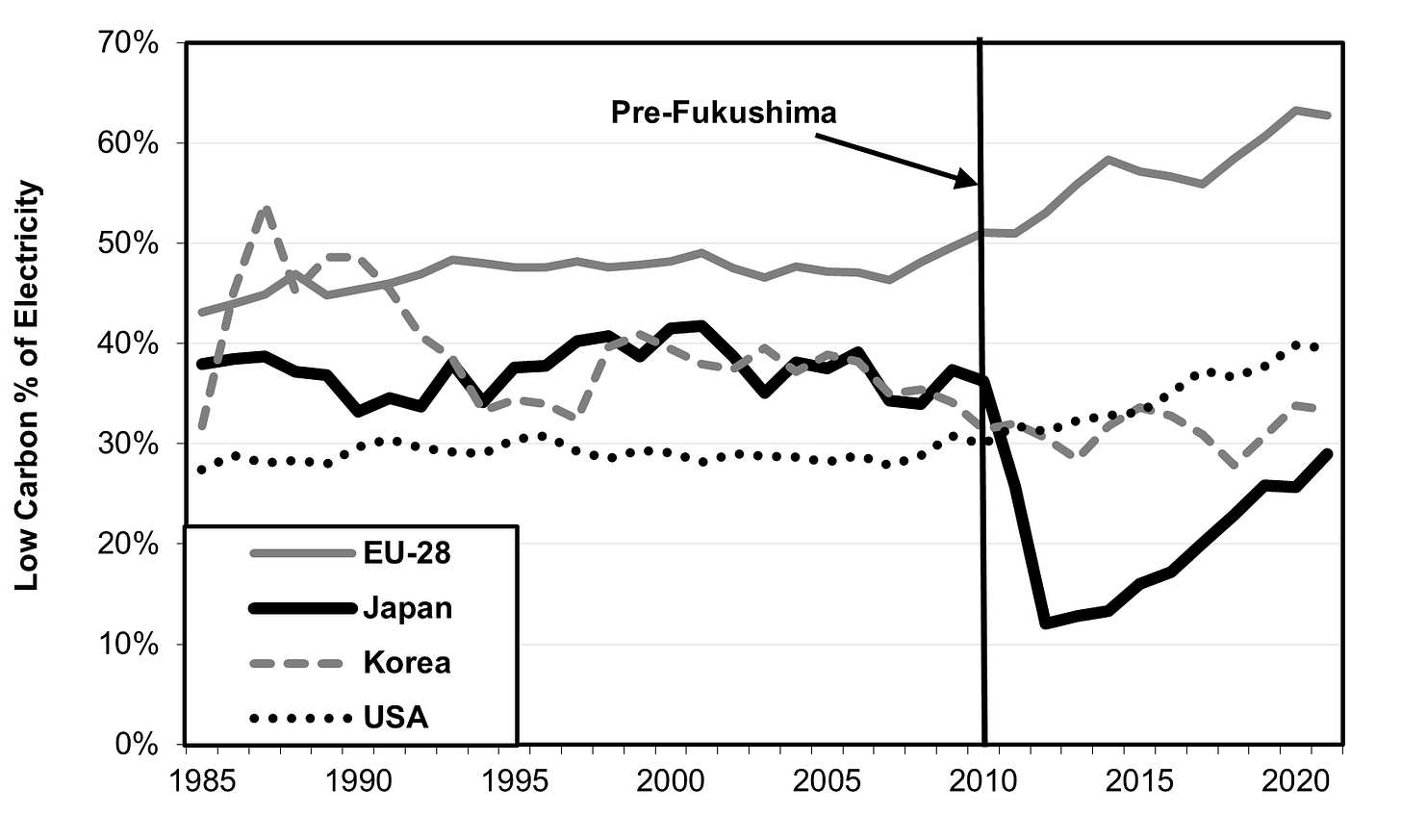

Until Fukushima, Japan’s energy was as clean, and for a while even cleaner, than in other rich countries, as measured by carbon emissions per unit of all energy (see chart at the top). Regarding electricity generation alone, in 2010, Japan was second to the EU in terms of low-carbon electricity (see chart below).

Source: https://nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/owid-public/data/energy/owid-energy-data.xlsx Note: Share of electricity generation from renewables and nuclear

Moreover, the 2010 Strategic Energy Plan (SEP) developed by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) projected further growth in low-carbon electricity via a substantial increase in nuclear and renewable electricity and a substantial drop in fossil fuels. Reducing energy imports, rather than cutting emissions, was METI’s primary motivation. That focus was a product of the two oil price shocks of the 1970s.

The 2010 SEP proposed to double Japan’s “energy self-sufficiency,” i.e., energy not imported, from its 18% level in 2007 to 40% by 2030. The share of electricity with zero emissions was to double from 34% in 2007 to 70% by 2030. Nuclear’s share would double from 26% to 50%, while renewables would double from 8% to 19%. Since hydroelectricity was already at its maximum, increased renewables would have to come from solar and wind. While reaching 19% in 2030 seemed very ambitious at the time, renewables have already surpassed that goal at 23%.

METI also wanted to halve Japan’s imports of oil, 90% of which came from the volatile Middle East. That required switching from gas-powered cars to hybrids and electric vehicles. So, the SEP set a goal to hike the share of low-emission vehicles in new car sales—hybrids, battery-powered EVs, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles—from 10% in 2007 to 50% by 2020 and 70% by 2030. That would reduce transport sector emissions per mile driven by 38% as of 2030.

At the same time, METI wanted the steel industry, which now produces about 15% of Japan’s carbon emissions, to switch from thermal coal to natural gas. It proposed reducing residential and commercial emissions by half by creating rules for new buildings. However, in these areas, because METI stuck to voluntary measures, little progress was made.

The plan projected a 30% reduction in energy-related carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 1990, the base year for the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Since Japan’s emissions had increased during 1990-2007, this would represent a cut of 40% from 2007 levels and would bring Japan halfway to its 2010 goal of an 80% reduction in emissions from the 1990 level by 2050.

DPJ vs. the LDP-METI-Keidanren Axis

Many of the proposals in the 2010 SEP emerged from a 2006 METI strategy document called New National Energy Strategy (NNES), but the NNES was focused more on energy independence than emissions reduction. The heightened attention to emissions by 2010 resulted in part from the victory of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in the 2009 Lower House election. The first DPJ Prime Minister, Yukio Hatoyama, announced that Japan would reduce carbon emissions from 1990 levels by 25% as early as 2020, a goal set out in the DPJ’s election manifesto. METI, the powerful Keidanren business federation, and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) all claimed that this goal was impossible to meet. The pledge of the previous LDP government was an 8% cut. As a compromise, the 2010 SEP announced a goal of a 30% reduction ten years later, by 2030, but METI did not really buy it.

When Hatoyama was replaced by Naoto Kan, the DPJ government stopped talking about the 2020 goal. Moreover, in a stunning move, the Kan administration renounced the Kyoto Protocol’s call for mandatory cuts in emissions during 2008-12. Another measure in the DPJ manifesto was a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions, something that has proved effective elsewhere. The Hatoyama administration tried and failed to include it in proposed legislation, and Kan dropped the idea. To this day, Japan still lacks any effective system for carbon pricing.

For details on assorted policy differences between the DPJ and the traditional policy-making elite, as well as within the DPJ, see this and this.

Despite the disagreements, a couple of lasting achievements emerged from the short period of DPJ rule. The most impactful was a “feed-in tariff” (FIT) for solar power plants. The FIT would guarantee purchases of solar power by the utilities at a high price, thereby incentivizing producers. The LDP had intended the FIT to apply only to surplus electricity, but the DPJ wanted it to apply to all solar-generated electricity. When the LDP returned to power, it adopted the DPJ’s formulation, perhaps because the Fukushima disaster made the need for solar power more urgent. The FIT is one of the biggest reasons that solar electricity has become a major power source in Japan over the last decade.

Japan Creates the Global Solar Power Industry

If not for Japan, solar power across the globe would cost much more and be far less widespread than it is. The road to commercial viability began a half-century ago with Japan’s Sunshine Project. The government supplied money, and worked with private firms, to make solar panels technically and economically feasible. Previously, solar cells were mostly known for their use in satellites and manned spaceships.

The Sunshine Project began in 1974, shortly after the 1973 oil embargo and quadrupling of prices, as part of Japan’s search for energy independence. The focus ranged from fundamental R&D to pilot projects, and various subsidies existed. As a result of decades of effort, Japan became the world’s biggest producer of solar energy panels, a status it held until 2008. Leadership passed to Germany and then China. One can only wonder whether Japan might have retained its leadership longer had Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi not ended solar subsidies prematurely in 2005. As the industry grew, learning curve effects and economies of scale sent costs plunging at a rate far beyond expectations. In a virtuous cycle, lower costs led to greater adoption by electric utilities all over the world, leading to even further cuts in cost. Within Japan, the subsidies resumed after Fukushima under the FIT scheme. That sent solar mushrooming from just 0.3% of electricity in 2010 to 10% in 2022 (see chart below).

Source: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Mar/Renewable-capacity-statistics-2023; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_power_in_Japan

To be sure, less successful attempts in other energy areas were also part of the Sunshine Project, but only governments have the wherewithal to fund a variety of such risky experiments, of which only some will succeed. Private finance could never have taken the risk of funding a technology that took four decades to pay off. This is not a case of the government fighting the market, but of leading it until costs become so low that government aid is no longer needed.

EVs Pioneered in Japan

Just as the 1973-74 oil shock spurred Japan’s efforts in solar power, it also spurred METI to develop battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs), seeing them as the best alternative to gasoline autos. METI (then known as MITI) began financing R&D for BEVs as early as 1976. Progress was slower than expected, and a series of plans evolved. In 1997, MITI added efforts in hybrids and vehicles powered by compressed natural gas, methanol, and hydrogen fuel cells. Hybrids were added partly in response to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate change, possibly because emissions reduction could be achieved more quickly. Previously, “the main ambition [was] replacing petroleum with electricity, hydrogen or natural gas in order to ensure energy independence.”

Unbeknownst to METI in 1997, Toyota was already working on the Prius and would put it on the market two years later. Perhaps Toyota stayed away from the METI efforts because it did not want to share its knowledge with competitors.

As early as the late 1990s, consumers were eligible for hefty subsidies for purchases of various low-carbon autos, including EVs. When Nissan (then under the leadership of Carlos Ghosn) came out in 2010 with the world’s first mass-produced BEV, the Nissan Leaf, Japanese consumers were given sizeable incentives, up to a maximum of ¥780,000 ($5,400) at today’s exchange rate). These days, the maximum is set at ¥650,000 $(4,500) for a BEV, ¥450,000 ($3,100) for a plug-in hybrid (PHEV), and a whopping ¥2,300,000 ($17,000) for a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle (FCEV). The size of the incentive depends on the range of the car: and its ability to pump excess electricity back into the home or office. Until 2019, the Nissan Leaf was the world’s top-selling EV; then, it was overtaken by Tesla.

In 2021, electrified cars accounted for more than 40% of Japan’s 3.67 million car sales, not that far from METI ’s 2010 goal of 50% by 2020. 97% of them are traditional hybrids, and most of the rest of either BEVs or PHEVs. Despite the gigantic incentive, consumers bought only 2,464 FCEVs. Continuing to throw money at FCEVs is not a case of catalyzing the market, but of trying to defy it, as are fossil fuel subsidies all over the world.

Because of the shift to hybrids, as well as increasingly stringent fuel mileage standards on gasoline cars, a new Japanese car has among the lowest emissions per mile of driving among rich countries. Progress in Japan and Europe have moved more or less in tandem (see chart below), while US emissions per mile are far higher.

Source: https://tinyurl.com/2p92stm5

The problem is that, as the cost of driving goes down—because people buy less gasoline per mile—many people drive more miles per year, sometimes because they’ll choose driving over using public transportation. Consequently, overall emissions may not go down. That happened in both Japan and Europe. In Japan’s case, total emissions from cars rose rapidly from 1990 through 2000 and then fell back afterward, leaving emissions in 2019 a bit higher than they were in 1990.

The answer is to move to BEVs and renewable electricity. Look at Norway, where, in 2022, BEVs comprised 30% of all cars on the road and 80% of new car sales. Emissions per mile are less than half of the rest of Europe. Whereas Norway’s total road transport emissions rose 7% from 1990 to 2012, after that, the spread of BEVs sent total auto emissions downward by 9%.

Fukushima Topples the Chess Table

The Fukushima nuclear disaster was a completely avoidable, self-inflicted calamity. Not only was Japan not following the world’s best safety practices, but also the electric utility at fault, TEPCO, had been falsifying safety records for years, while METI regulators turned a blind eye. The alliance of utilities, METI, and the LDP, nicknamed “the nuclear village,” destroyed nuclear’s credibility.

That changed everything. All nuclear plants shut down for a while, few have been restarted due to public opposition, and it remains unclear how many will ever restart. In response, Japan turned to coal. Emissions rose (see first two charts again).

It also changed the policy battleground. In some ways, METI, the LDP, and Keidanren moved backward. For example, the government now favors a “go slow” policy on fossil fuel, refusing even to phase out coal. Instead, it dreams of “clean coal” via carbon capture. In other areas, like the FIT, the government has shifted in the right direction. Equally important, hundreds of climate-friendly corporations outside of heavy industry formed new organizations to spur decarbonization, e.g., the Japan Climate Leaders Partnership. For the first time, they have gained seats, and some real influence, on governmental advisory panels.

This post-Fukushima political shift will be detailed in the next installment.

"Because of the shift to hybrids, as well as increasingly stringent fuel mileage standards on gasoline cars, a new Japanese car has among the lowest emissions per mile of driving among rich countries."

Here, I'd like to add that having around a third of newly sold cars in Japan being kei cars also helps on the emissions front.

you really outlined the scale of the missed opportunity...