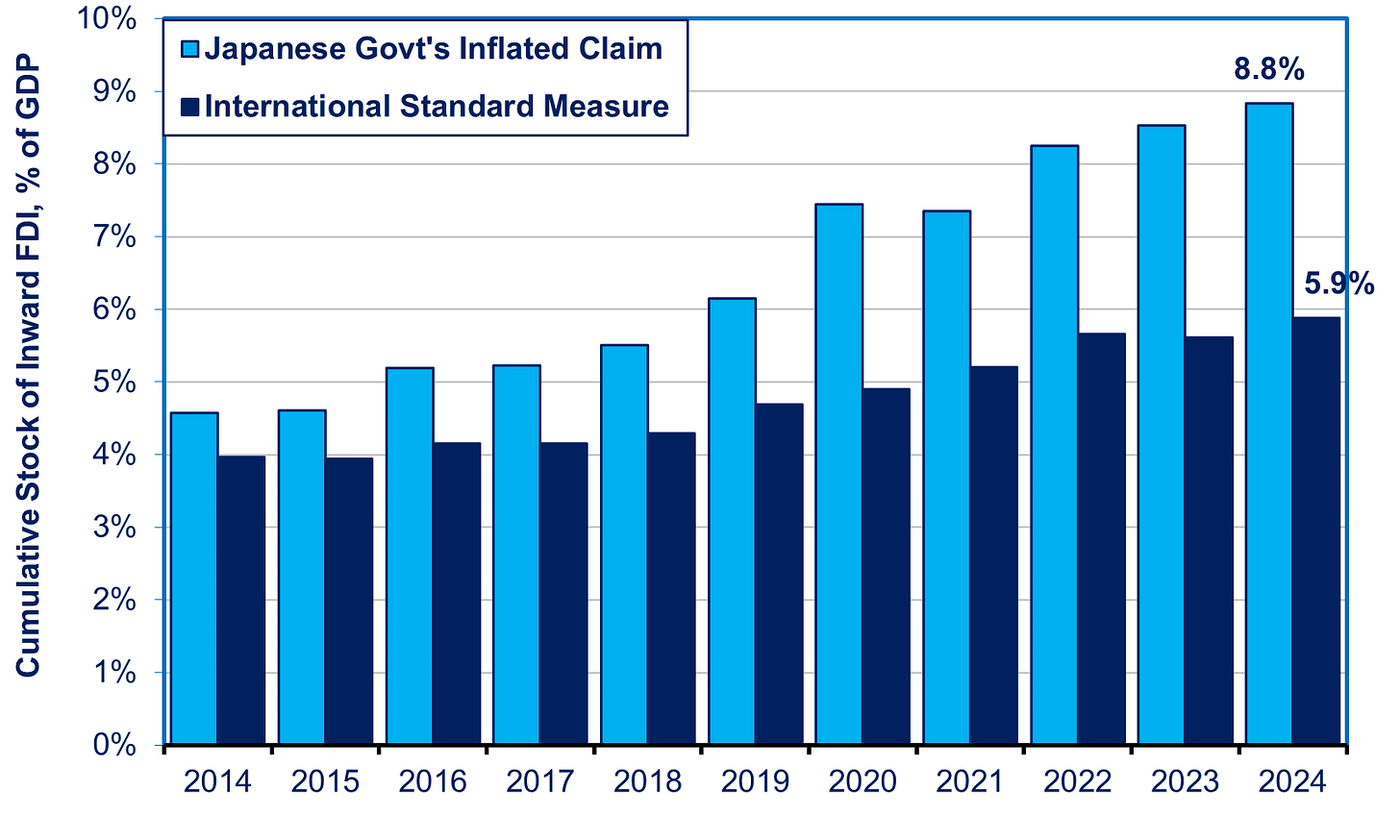

Source: https://www.mof.go.jp/policy/international_policy/reference/iip/qiipm6.xls and Note: The international standard measure is published by UNCTAD using standards set by the IMF and OECD. For further explanation, see the text.

Guess what, folks. Japan is still 196th, still behind North Korea.

Back in 2021, readers of this blog and Toyo Keizai were shocked when I ran a piece entitled Japan as 196th. The piece showed that, out of 196 countries tracked by UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) in 2019, Japan came in 196th when it came to the cumulative stock of inward Foreign Direct Investment as a percentage of GDP. FDI occurs when a foreign company either creates its own operations on Japanese soil or buys at least 10% of an existing Japanese company.

Nonetheless, despite all the progress claimed by Japan, as of 2023, UNCTAD reports that Japan was still 196th. The stock of FDI stood at 5.9% of GDP. While that was up from 4.4% in 2019, Japan was chasing a moving target. So, like someone on a treadmill, Japan had to run fast just to stay in place. Scholars Takeo Hoshi and Kozo Kiyota calculated that, if Japan performed like other countries with similar characteristics, the ratio of inward FDI to GDP would have already reached a very impactful 35% of GDP by 2015, just from the six leading countries investing in Japan.

Six Impossible Promises Before Breakfast

Now, Japan promises to run even faster on that treadmill. In 2023, it projected cumulative inward FDI to reach ¥100 trillion ($700 billion) by 2030. Reportedly, the Ishiba administration may raise the target to ¥120 trillion ($840 billion). That would equal 17% of nominal GDP if the IMF’s forecast for 2030 GDP is correct. While 17% in 2023 would have put Japan at 175th among 199 nations, that is still a long way from the 1.0% level in 2000 and 6% in 2023.

But is that goal at all realistic? Or is it like so many other lofty goals set by the government that have little basis in reality? All too often, to borrow from Lewis Caroll, the Japanese government makes six impossible promises before breakfast. ¥120 trillion by 2030 would require six straight years of 14% annual growth. Japan has never even come close to that. While the MOF asserts that Japan did achieve 10% a year between 2018 and 2024, that claim is based on flouting international accounting rules and the misleading impact of a depreciating yen on FDI statistics. Before explaining that, let me first discuss why we care. At the end, I’ll discuss why inward FDI is so low.

Why Should We Care?

Decades ago, economists discovered that countries with more inward (and outward) FDI grow faster (see Chapter 15 of The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future for the sources for this information, as well as greater elaboration). A study of 19 OECD countries confirmed that FDI improved economic growth in rich countries, mainly by raising productivity.

Even the little inward FDI that Japan has done shows what Japan is missing by not having more. Compare, for example, the impact on Japanese companies when a foreign company bought a domestic manufacturer (a mere 67 cases during 1994–2001) versus an acquisition by another domestic firm (1,362 cases). The ones purchased by foreigners showed twice as big an improvement in Total Factor Productivity (TFP), i.e., productivity of both labor and capital. The greater the share of foreign ownership in a firm, the higher that firm’s spending on R&D, the number of patents generated, sales growth, exports, profitability (return on assets), and productivity.

What’s really important is that, when foreign-owned firms in Japan conduct R&D, they generate seven times as much spillover productivity benefits at other firms (suppliers, customers, even competitors) than do domestic firms spending the same amount. One scholar concluded that this is “probably because knowledge of foreign firms is often new to domestic firms.”

Bending the Rules To Inflate The Numbers

The MOF uses two tricks to inflate Japan’s FDI numbers. To see the first, look at the chart at the very top of this blog. The MOF claims that, in 2024, Japan’s stock of inward FDI added up to ¥54 trillion ($377 billion at current exchange rates), or 8.8% of nominal GDP. In reality, according to the accounting rules laid down by the IMF and OECD, and followed by UNCTAD, the stock was just ¥36 trillion ($248 billion), i.e., 5.9% of GDP.

What accounts for the difference? The MOF counts as part of FDI something that the IMF and OECD say should not be counted: loans to Japanese parent companies from their own affiliates overseas. These loans are counted when one is looking at financial flows in the balance of payments, but an OECD spokesman was very clear that they should not be counted when one is looking at FDI to look at progress over time or to compare one nation to another. FDI refers to injections of capital from foreign companies, not Japanese affiliates located overseas. The only items that should be counted are new money (equity) invested in Japan and reinvested profits from existing affiliates. Over time, such loans became an increasingly large share of alleged inward FDI as counted by the MOF: from ¥3.2 trillion ($22 billion) in 2014 to ¥18 trillion ($124 billion) by 2024 (see chart below).

As a percentage of total FDI alleged by the MOF, such loans rose from 13% in 2014 to 33% in 2024 (see chart below). In fact, just about half of the entire alleged growth in FDI from 2014 to 2024 came from such illegitimately counted loans.

Weaker Yen Creates Statistical Illusion

There is another element that has made the growth in FDI appear larger than it really has been. That is the depreciation of the yen. Investors in Japan use dollars, euros, etc., but change those dollars into yen. UNCTAD, the IMF, etc., measure the dollars invested. When the yen is weakening, this distorts the apparent growth when measured in yen. For example, from 2020 to 2023, UNCTAD figures show that the amount of stock of FDI actually fell slightly (about 1%) from $250 billion to $247 billion. However, due to the depreciation of the yen during that period from ¥107 per dollar to ¥141, each dollar coming in bought 31% more yen in 2024 than it had in 2024. Hence, in yen terms, inward FDI appeared to rise from ¥27 trillion to ¥35 trillion. We can see the impact in the chart below when we see the emerging big gap in the last few years between the black line (showing FDI in yen) and the blue column (showing FDI in dollars).

Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.FdiFlowsStock

What would the picture have looked like if the yen had not been deliberately weakened under the policies of Abenomics from 2014 through 2024? In 2024, inward FDI, as measured properly under the international rules, equaled 4% of Japanese nominal GDP. Due to the yen’s depreciation, inward FDI appeared to rise to 6% of GDP. Suppose, however, that the yen had not depreciated. Then the amount of dollars coming in would have translated into yen terms to just 4.4% of GDP, not 5.9%. That’s not much above the 4% figure for 2014 (see chart below)

.What will happen if the yen recovers some of its past value? In that case, the opposite impact will occur; dollars coming in will translate into fewer yen and, when measured in yen, FDI’s share of GDP will not grow as much. It could even fall, even if it is still growing in dollar terms.

Bottom Line

So, here’s the upshot when we eliminate these two distortions. The MOF claims that the stock of inward FDI in 2024 equaled ¥54 trillion, 8.9% of GDP. Eliminating the improper accounting rules shows the stock at ¥35 trillion, or 6% of GDP. Adding in the elimination of the impact of yen depreciation shows the stock at ¥26 trillion, or 4.4% of GDP. The net result is just half of what the MOF claims.

Tokyo’s “Action Plan” Leaves Out the Most Important Factor In Making Japan 196th

In 2023, the government issued its latest “action plan” on attracting more inward FDI. Like its predecessors, it omits the most crucial factor: most companies foreigners want to buy are not for sale. When Tokyo thinks of inward FDI, it primarily desires foreign companies setting up new operations in Japan, like TSMC’s semiconductor plant in Kumamoto. However, in rich countries, over 85% of inward FDI is foreign companies buying healthy domestic firms. Such acquisitions are rare in Japan.

Japan is clearly attractive to foreign businesses, due to its large, affluent market, a very well-educated workforce and customer base, and high technological capacity among potential suppliers and partners. In a 2025 “FDI Confidence Survey” of senior executives around the world, Japan ranked the fourth most attractive place to invest.

The press is filled with instances of gigantic rescue purchases, like Renault’s investment in Nissan and Foxconn’s takeover of Sharp. However, the usual Japanese target for foreign acquisition is not a company needing rescue. On the contrary, it is companies with higher profits, better technical capacity, and a greater willingness to adopt new practices than the typical firm in its industry. Foreign firms also select fairly sizeable companies. During 1996-2020, foreigners paid $112 million for non-group companies on the stock market.

Unfortunately, the most attractive targets are out of reach because they belong to corporate groups, the vertical keiretsu. Japan’s 26,000 parents and their 56,000 affiliates employ 18 million people, a third of all employees in Japan. During 1996-2020, foreigners were only able to buy a trifling 57 members of corporate groups, whereas they were able to buy around 3,000 unaffiliated companies (see chart below). I’m trying to get updated data but I doubt it will change the picture.

Source: https://madb.recofdata.co.jp/

Since 2020, the government has tightened its regulations for investing in companies deemed critical to national security and it has sometimes abused the regulations, e.g. an attempt to buy a convenience store chain on a security pretext. Still, the main impediment is not government action but keiretsu refusal to unload affiliates even if selling would improve performance.

See this for more details on this story and what it means for Japan.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To provide more support, donate several subs at $50 each. You do not need to name the sub recipients, just how many. This is a one-time contribution; it does not repeat automatically. Please click the button below.

Katz is out of his mind. Why does he want Japan lists offers its jewels for sales to patented predators and "extortionists" ? Doesn't he realize the world has changed since he went to school?