Japan Unlikely To Meet 2030 Goal For Emissions Reduction

On Climate Change, Economic Fundamentals Are Necessary But Not Sufficient

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-electricity-coal

Necessary but not sufficient. That’s the key phrase describing the relationship between economic fundamentals and achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Without economic growth and tumbling prices for renewable energy, green policies would face extremely severe headwinds. Fortunately, these economic forces are already promoting some decarbonization. Nonetheless, “business usual” is nowhere near strong enough to reach net zero. Government measures are needed. Unfortunately, the current 2030 goals of many governments, including Japan—even if fully implemented—are not ambitious enough to meet the 2050 deadline.

Consider the case of coal. The low prices of solar and wind power should induce utilities to phase out the existing coal-fired plants at a rapid pace. That is happening in the European Union, which is halfway toward a government-mandated shutdown of all its coal plants by 2030. In the US, where there is no federal mandate, companies are shutting down many plants on their own. However, under current trends, there will still be a substantial number in the 2040s. In Japan, it’s even worse. The government and the Keidanren business federation are trying to maintain coal indefinitely under the rubric of energy stability and dreams of carbon capture. Consequently, while the terawatt-hours of electricity generated yearly from coal are far below their 1985 level in the US and Europe, they have tripled in Japan (see chart above).

While Japan is phasing out some of the most polluting coal plants, it is currently building and/or planning to build new coal-fired plants equal to 8% of existing capacity. As detailed below, there’s a good chance that Japan will not even be able to fulfill its extremely modest plan to reduce coal’s share in electricity generation from 30% to 26% by 2030.

Meanwhile, at the May 2022 Group of Seven meeting, Washington and Tokyo together blocked a proposal to set a 2030 date to phase out all “unabated” coal plants. Consequently, the G7 pledged a phase-out but with no deadline. The term “unabated” allows Japan to keep running plants it calls ultra-critical in terms of emissions and would also allow plants with carbon capture technology. The latter is not economically feasible and may never be. To make matters worse, US Supreme Court has severely restricted the ability of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate carbon emissions.

Economics And Politics In Reaching Climate Goals

To reach net zero emissions, two big trends are required. The first is reducing the amount of energy it takes to produce a dollar of GDP. This comes automatically with economic development. The second requirement—reducing and then virtually eliminating the carbon content of energy—is far from automatic. Let’s look at the data.

Once poor countries reach a certain level of development, as real per capita GDP goes up, the amount of energy per dollar of GDP goes down (see chart below).

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions

However, as poor countries become richer, per capita GDP rises faster than energy-intensity declines. Consequently, per capita energy consumption—electric lighting, heating and cooling, modern appliances, cars, modern industry—rises rapidly and that’s part of the rise in living standards. Once a country becomes rich enough and services rise as a share of GDP, per capita consumption of energy decelerates, then flattens out, and eventually declines (see chart below). America’s energy use per capita topped out in 2003 and fell 15% by 2019. Japan, too, is down 15% from its 2005 peak.

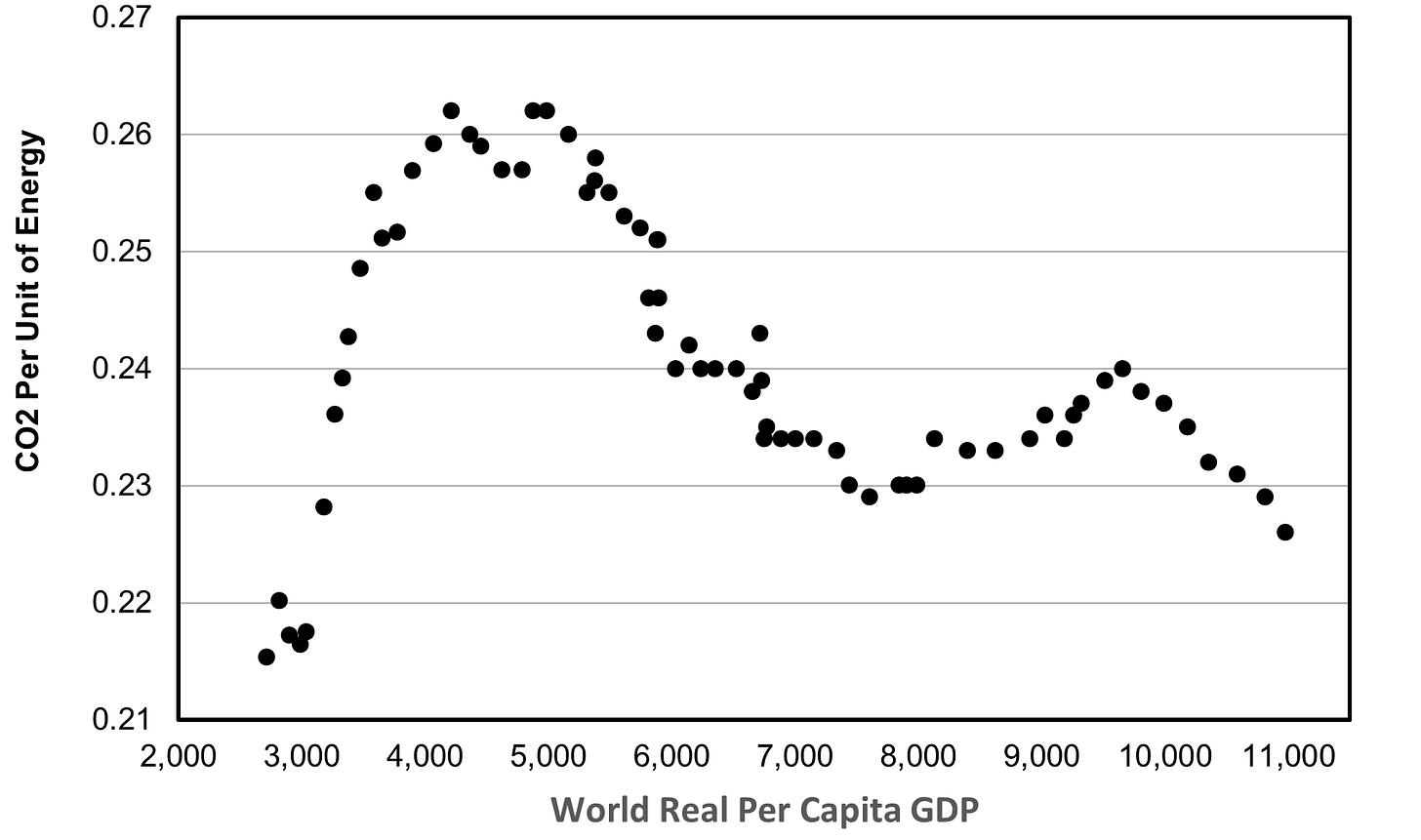

By contrast, decarbonizing energy is more problematic. As poor countries develop, CO2 per unit of energy rises, then tops out and declines as they reach middle-income status. Finally, as they approach affluence, further declines come harder (see chart below).

Some progress is being made in the richest countries, but the pace depends less on economics than on interest group politics. From 2012 to 2019, Japan reduced emissions per unit of energy by 10% while in the US it’s down 14% from 1981. By contrast, in the European Union, which is more committed to decarbonization, it’s down 40% from 1965.

Once a country has hit a certain level of per capita GDP, additional progress on emissions has very little linkage to per capita GDP. Japan in 2018 ranked 14th among 30 countries in per capita GDP in 2018, but 4th in CO2 per unit of energy (see chart below).

Note: The trend line does not include two outliers Poland (very coal-dependent) and Sweden (very dependent on hydro and nuclear)

Japan Passes Up Low-Hanging Fruit

Japan is not likely to meet its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 by 46% from the 2013 level. Even if it could, experts say a 62% reduction by 2030 is necessary to be on track for net zero by 2050. Japan could meet its goal if it stopped passing up opportunities to grab the low-hanging fruit.

Japan’s 2021 Strategic Energy Plan hinges upon reviving nuclear power to 20-22% of all electricity generation by 2030, up from just 6% in 2019. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has vowed to have 9 nuclear plants operating this winter and 17 by next summer, up from just six now. However, for years, Japanese local governments have been able to block reopening most of the plants shut down in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima catastrophe—even the 17 approved by the Nuclear Regulation Authority. Kishida’s call will test whether the Ukraine war has changed their minds. While some more plants are likely to be reopened, hitting 20-22% of electricity is not realistic. What then will fill the gap? Coal and natural gas. That jeopardizes the goal of reducing coal’s share to 26%.

Tokyo plans to raise renewables (including hydropower) to 36-38% of electricity. That is realizable since the country is already on track to bring it to around 34%. To achieve the 2030 emissions goal, renewables would have to hit 40-50% of electricity generation, a feasible goal according to a 2021 statement signed by nearly 100 leading Japanese corporations affiliated with the Renewable Energy Institute.

Steel production alone accounts for a stunning 17% of all carbon emissions in Japan when the emissions involved in electricity production are included. The reason is simple. Japan’s old-fashioned blast furnaces emit four times as much CO2 per ton of steel as more modern electric arc furnaces (EAFs). Yet, only 25% of Japanese steel is made with EAFs, compared to 43% in the EU and 77% in the US. As a result, out of 17 countries, Japan comes in fifth in CO2 per ton of steel. Since EAFs need scrap steel, not all the world’s steel could be made with EAFs, but there is enough scrap to substantially increase the portion in Japan and elsewhere.

Autos account for 20% of Japan’s carbon emissions (not counting emissions created in manufacturing the vehicles). Unfortunately, powerhouses like Toyota have not only dawdled on producing electric vehicles, but have actively lobbied against them in both Japan and foreign markets. On Sept. 29, Akio Toyoda stated that, “Realistically speaking, it seems rather difficult to really achieve” California’s new requirement that bans sales of gasoline vehicles and regular hybrids after 2035 (plug-in hybrids are permitted). If Toyota sticks to this stance, it would be giving up a huge market since as many as 15 American states automatically follow California’s regulations on emissions. Ford, by contrast, applauded the new regulations.

While EVs are expected to increase from a measly 1% market share in 2021, Japanese automakers talk of reaching just 20-40% by 2030, compared to 50‑70% in the US and 75-85% in Europe.

Japan and the US could achieve much more progress using existing, financially feasible technologies. So far, domestic politics in both countries limits this.