Japan’s Minimum Wage Miracle

Lifting Wages of 20 Million, But Without The Job Losses Business Lobbies Predicted

Source: OECD at https://tinyurl.com/5apy7r5h Note: The dark blue area shows the real minimum wage more than doubling in constant 2020 yen. The percentage numbers show the minimum wage relative to a median full-time worker. See text for further explanation.

It has taken a couple decades, but Tokyo has finally raised the minimum wage enough to lift almost 20 million workers above levels close to, or even below, the poverty level. The real (price-adjusted) minimum wage has doubled since 1978 and is up 31% since 2007, when the Minimum Wage Law was revised (see chart at the top). This has improved both lives and consumer purchasing power, the latter indispensable to economic recovery. Equally important, a higher minimum wage did not destroy jobs, as was inaccurately predicted by business lobbies. On the contrary, employers are hungry for job-seekers.

The law was revised due to public outrage that people on minimum wage still needed public assistance in at least 12 prefectures—including populous Tokyo, Osaka, and Kanagawa. Then, in 2010, the short-lived Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government proclaimed the goal of a ¥1,000 ($6.70) minimum wage by 2020 (it was finally reached in 2023). Someone working full-time at today’s minimum wage (¥1,054) would earn a bit more than ¥2 million ($14,000) per year, the level below which people are considered poor. Those earning below ¥1.5 million qualify for public assistance.

A higher minimum wage helps not only those below it but also millions who earn substantially above it. As the minimum wage rose, Japan saw a plunge in the share of full-time workers officially labeled low-paid because they earn less than two-thirds of the median full-time wage. In 2023, that meant those earning less than ¥1,460 per hour. As the minimum wage rose, the share of full-time women in the low-paid category plunged from almost half (45%) in 1985 to just 18% these days (see chart below).

Source: OECD at https://tinyurl.com/3rz9u7h4 Note: Low-paid workers are full-time workers who are paid less than 67% of the median wage for all full-time workers; i.e., women’s salaries are compared to the median among both sexes. These figures do not include part-timers. See text for further explanation.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a 2016 report, each 1% rise in the minimum wage should lift total wages in Japan by 0.5%. As I’ll explain below, this failed to happen because companies kept replacing regular full-time workers with much lower-paid non-regular part-timers and temporary workers. As a result, the median hourly pay of a full-time worker is no higher than in 1993 (see again chart at the top). The average real hourly wage of all Japanese workers—not just full-timers—is down 10% from its 1997 peak (see chart below).

Source: https://tinyurl.com/4safjz46 Note: This chart shows all workers; the chart at the outset showed just full-timers

The minimum wage has proven to be the single most beneficial step Tokyo has taken to improve income and consumer purchasing power. The benefits are so widely recognized that a couple years ago, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida called for raising the minimum to ¥1,500 ($10) by 2035 and now Shigeru Ishiba has proposed reaching that goal by 2029. That time horizon seems extremely unlikely. It was hard enough for Shinzo Abe in 2016 to create a consensus around raising the minimum by 3% each year (a standard that was only reached some of the time; see chart below). Ishiba’s schedule would require a 7.3% annual hike. In the summer, Japan’s biggest labor union federation, Rengo, called for ¥1,600 to ¥1,900 ($12.75) by 2035.

Source: OECD at https://tinyurl.com/5apy7r5h

Helping Nearly 20 Million

When Shinzo Abe called for a 3% annual hike to reach the ¥1,000 goal, 18 million Japanese earned less than ¥1,000. That equaled a full third of all non-executive employees. When in 2022 the minimum wage was raised to ¥961, 20 million were earning less than that.

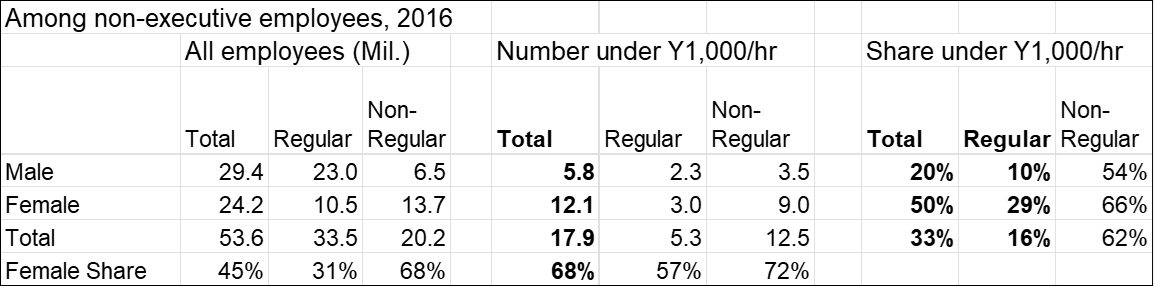

Two-thirds of these 20 million were women. Partly, this was because so many of the women were non-regulars, i.e., part-timers and temporaries, and partly because, even when women have regular jobs, i.e., job security, they are still discriminated against. But it wasn’t only non-regulars that were paid so little. In 2016, 10% of male regulars and 30% of female regulars earned under ¥1,000 (see table below).

Source: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16232.pdf and https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000031831358&fileKind=0

Until the lost decades, a high minimum wage was not considered necessary. That’s because, even as late as the 1980s, Japan had an unusually equal distribution of wages. Consequently, in 1991, it seemed not to hurt that many people that Japan came in last among 16 wealthy countries with a minimum wage equal to only 29% of the hourly wage of a full-time worker. In the typical rich country, the ratio was 52%.

However, as the lost decades wore on, that equality disappeared. Companies increasingly hired non-regular workers whom they could lay off when necessary and pay much lower wages. Japanese law mandates equal pay for equal work between regulars and non-regulars, but the government does not enforce it. As a result, in 2019, while the average regular worker was paid almost ¥2,400 per hour (including bonuses), part-time workers were paid on average just ¥1,100 (female) and ¥1,200 (male) per hour. Non-regulars overall (temporaries and others as well as part-timers) were paid around ¥1,500 on average. Of course, millions of non-regulars were paid much less than these averages. By the 2010s, non-regulars had reached nearly 40% of all employees (see chart below).

Source: http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/lngindex.htm

While this raging inequality and genuine hardship created pressure to raise the minimum wage, as noted above, progress was slow (see chart higher up on annual percentage hike). Then, in 2016, when the Bank of Japan’s campaign to reach 2% inflation was floundering, and the BOJ decided that wage increases were necessary to achieve its inflation goal, Abe responded. He called for raising the minimum by 3% each year. Today, the issue is whether to aim for ¥1,500 and, if so, how long to take.

The Minimum Wage and Jobs

For decades, business lobbies and many orthodox economists argued that hiking the minimum wage would cost many jobs. However, lots of “natural experiments” showing insubstantial losses—along with less simplistic economic models—have changed the consensus. Most studies done after the year 2000 show that gradual hikes in the minimum wage cause a job loss close to zero, or even a small gain. (The reason for a job gain is that “monopsonistic” employers hire fewer people at a lower wage than would prevail in a more competitive market. In such a situation, a higher minimum wage can actually boost jobs.)

The US went through a similar experience. Beginning about a decade ago, many states and cities raised their minimum wage to $15 (¥2,200). Just 13% of American workers now earn less than $15, way down from 32% just a few years ago. Still, jobs are growing, and unemployment is still low—even among young workers who are often paid the minimum.

The above-cited IMF report recommending a hike in Japan’s minimum wage reflects the impact of the new research.

Why, Then, Have Average Hourly Wages Fallen 10% Since 1997?

If each 1% hike in the minimum wage is supposed to raise total wages by 0.5%, as the IMF calculated (see above), then why is the real hourly wage among all workers 10% lower than in 1997 (see again the chart higher up)?

The main reason is the rise in non-regulars from 15% of all employees in 1984 to 38% (see chart higher up). To see why, let’s consider the impact using the simulation in the table below:

To simplify, let’s pretend in this simulation that there was no change in either the regular or non-regular wage. Nonetheless, the average employee's pay fell by 9% simply because of the change in the ratio of regulars to non-regulars.

In reality, between 2009 and 2019, the real wages of non-regulars rose by almost 8%—largely due to the higher minimum wage—while wages of regulars have gone up by less than 2%. Still, due to the shift to non-regulars, the average fell.

Why Have Wages Of Full-Timers Been So Flat?

In the chart at the outset, we saw that the real wages of the median full-time worker today are no higher than in 1993. The main reason is wage and promotion discrimination against women (see Chapter 8 of my book, The Contest For Japan’s Economic Future). The average female full-time worker is paid 25% less than men. As with non-regulars, the law mandates equal pay for equal work, but it is not enforced. And so, just as companies switch to non-regulars to cut average wages, they do the same with women among regular workers. From 2013 to 2024, companies increased the number of male regular employees by only 3% (just 470,000). By contrast, they hiked the number of female regulars by 26% (2.67 million). In fact, companies have not increased the number of male regular employees since just before Covid (see chart below). The same arithmetic that we saw in the table above on regulars vs. non-regulars applies to gender pay.

Source: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000031831368&fileKind=0

What About Male Regulars?

Even full-time male regulars have found their wages suppressed by all this wage discrimination. From 2000 to 2019, their real hourly wages were flat (just 0.6% in total over 19 years).

For one thing, companies have used the threat of replacing male regulars with their lower-paid counterparts to exert downward pressure on wages. While the law prevents mass layoffs of male regulars, big conglomerates can switch them from the parent company, where wages are high, to some of their subsidiaries where wages can be much lower.

Beyond that, Japanese unions are not only weak but have declined in membership from a third of all workers during the high growth era to just 16% now, mostly at the very big companies. Throughout the rich countries, wages have suffered most where unions have gotten weaker.

Finally, while Japan’s lifetime employment system provides job security for regular workers, it also suppresses wages by hindering these workers from moving to another company in search of higher wages. Wages are higher in countries where companies have to compete to retain good workers. In fact, as I detail in Chapter 11 of The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future, the initial impetus for creating lifetime employment in the early 1910s was to stop workers from driving wages higher by shifting jobs. One positive sign is that increased labor mobility among younger, highly-skilled workers has improved their wages.

Conclusion

A steadily rising minimum wage has been of great benefit, but it is not sufficient. For a decade, economists expected a labor shortage to force salaries upwards. This, too, has not been enough despite some positive signs among the most skilled younger employees. Other steps are necessary, including the enforcement of equal pay laws.