Japan’s Technological Prowess Should Enable 2.3% Per Capita Growth, Part I

It Needs To Convert Technological Inputs Into Economic Output

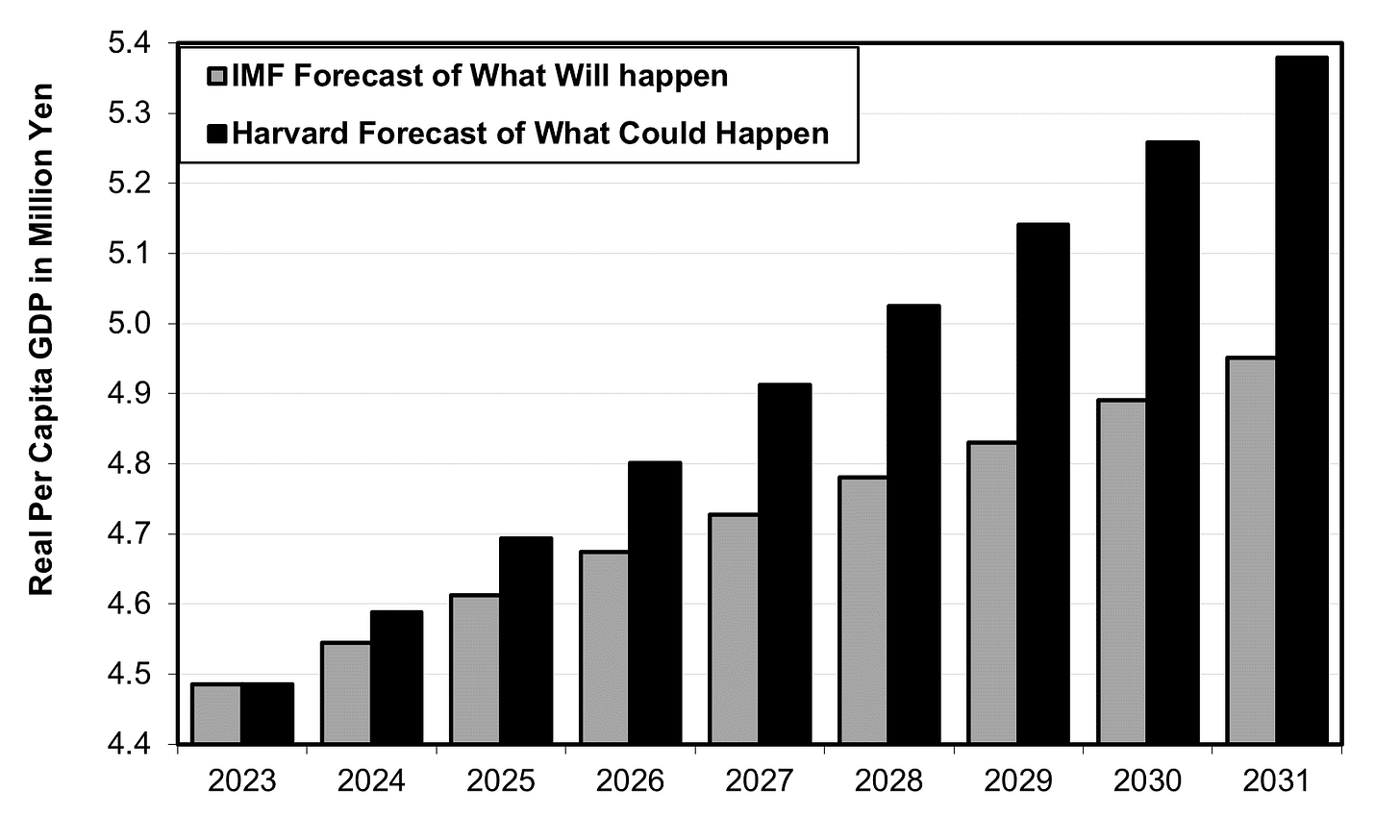

Source: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April/select-countries?grp=119&sg=All-countries/Advanced-economies/Major-advanced-economies-(G7) and https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/growth-projections Note: IMF projected growth rate extended two years by the author.

This is a “silver lining in the dark cloud” story. On the one hand, according to the Harvard Growth Lab, Japan’s per capita GDP could grow at 2.3% per year if it were as good as other countries in capturing the benefits of its technological prowess. That’s almost double the current rate of per capita growth.

Using a measure of technological strength called the Economic Complexity Index (ECI)—where Japan comes in first among 133 countries—the Harvard team projects that Japan’s real GDP could grow 1.8% a year between 2023 and 2031. While that would still leave Japan’s growth rate at a dismal 118th among these countries, it’s almost twice the 0.9% average pace Japan has suffered since 1991. Given Japan’s population decline of 0.5% a year, that translates into 2.3% per capita growth, a good rate for a rich country. In that scenario, average per capita GDP would grow 20% in just eight years.

The dark cloud is that no one really expects Japan to achieve that 2.3% pace under current conditions and policies. On the contrary, the IMF expects total GDP to grow just 0.7% a year through 2029, and per capita GDP to grow only 1.2% per year (see chart at the top).

The reason for the shortfall is clear. While scientists and engineers can produce new inventions, it takes companies to transform those innovations into economic value. Think of SONY and the transistor. But, these days, Japan’s companies come up short. For one thing, Japan’s financial and labor systems are so rigid that not enough capital and labor flows to the most innovative existing firms, let alone new firms with untapped potential. In the US, when the stock of patents held by a company increases by 10%, the financing (debt and equity) going to those firms rises by 3.5%. The comparable numbers in Sweden, Belgium, and the UK are 2-3%. However, in Japan, as well as Germany, Spain, and France, it’s just 1.5%. Due to lifetime employment, it’s far worse when it comes to reallocation of labor. Among American firms, a 10% hike in the stock of patents leads to a 2.2% hike in their labor force. It’s 1.5% in the UK, 1.3% in France, and 0.8% in Germany, but Japan comes in dead last at 0.5%. How are innovative companies to grow if they cannot get enough funding and talented, experienced staff? How are new companies to get off the ground? (For details, see The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future, Chapters 11 and 13.) Even when companies do get the necessary resources, they don’t always use them well. Japan throws a lot of money at digital technologies, but in 2023, it ranked a dismal 64th out of 64 economies in “digital agility of companies,” i.e., how much improvement it got in sales, profits, and productivity as a result of that investment.

The silver lining is that companies greatly improve their performance when they face fierce competition. More new technologies are deployed when new companies not anchored by old habits can proliferate. If Japan undertook the required business reforms, it could grow at a rate commensurate with its technological assets. It is not doomed to low growth by forces beyond its control.

Technology and Harvard’s High Projection

A country’s technological capacity is a major factor in how fast it can grow—once one factors in basics like a country’s level of per capita GDP, the growth rate of its labor force, the rate of investment in business and infrastructure, and the educational level of the population.

Japan comes in first in the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) for production and exports as measured not only by Harvard but also by the Global Innovation Index (GII) put out by The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The ECI measures how many different technologies are used to make a single product and how many countries are capable of using those technologies. Generally, the more complex the technologies and the greater the number of them per product, the fewer countries can master them and make those advanced, high-value products. Lots of countries can make steel; few can turn metals and other materials into a jet plane.

The Harvard Growth Lab contends that ECI predicts the growth of 133 countries five times more accurately than any other single measure, such as the World Economic Forum’s Competitiveness Index. If so, what does its failure in the case of Japan tell us about Japan?

Why The ECI Gets Japan Wrong

For one thing, ECI measures only one dimension of technological strength. WIPO’s GII, which examines 132 countries using more than 100 different dimensions, ranks Japan at only 13th among all the countries, not first as with the Harvard Growth Lab.

Secondly, we have to look more closely at why Japan ranks #1 on the ECI. Economist Dany Bahar and his co-writers found that, paradoxically, Japan rose in the ranks as it became less competitive. Bahar et. al. report: “After growing at an annualized rate of 10.9% from 1962 to 2010, [the export] growth rate flattened to 0.26% from 2010 to 2021. In terms of exports per worker [emphasis added], they even shrank at an annualized rate of -0.32% from 2010 to 2021. Although export growth also slowed down in Germany and the United States...., they still grew by more than 2% yearly, on average.”

One reason exports slowed is that, by 2021, according to Bahar et. al., Japan had lost its comparative advantage in nearly half (190) of the 394 industries where it had previously enjoyed comparative advantage from the 1960s onward. Yet, the industries where it still enjoys high competitiveness are far more complex in their technological makeup. And having fewer, but more complex, exportable products has lifted Japan’s ECI score.

This calls into question Japan’s prospects. What happens when demand for certain important and lucrative products shrinks, or even evaporates? Canon and Nikon, for example, were high-flyers when film technology dominated cameras and they were masters of a host of complex technologies, which Canon exploited in a wide variety of office products. But when cameras turned digital and became part of cell phones, Canon and Nikon sales shrank. Nikon’s revenue peaked at ¥1 trillion in 2013 and was only ¥628 billion in 2023 (having dropped from $6.7 billion to $4 billion). Revenues for the more diversified Canon peaked in 2007 at ¥4.4 trillion ($28.4 billion) and are now just ¥4.0 trillion. So, these companies have to reinvent themselves, partly by moving into products that incorporate some related, but unfamiliar technologies. Companies in all countries face this issue.

But here’s the problem. While Japan ranks number one in the ECI index of current Economic Complexity, it has increasingly lost its previous stellar ability to incorporate and adapt new technologies. This is measured in the Complexity Outlook Index (COI). By the first lost decade, in 1995, Japan’s COI ranking was already a low 39. Since 2010, its rank has fluctuated around the truly miserable average of just 85 (see chart below).

Source: https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/rankings

Worse yet, if a product requires 100 complex technologies, and you can master only 98 or 99, you cannot make it. So, how well will Japan’s automakers do as Electric Vehicles increasingly replace conventional gasoline cars (even if it takes longer than previously hoped for)? How well will makers of all sorts of machinery and chemicals do as products increasingly incorporate software, an area where Japan is weak?

What About The Products Where Japan Dominates the Global Market?

There are those who claim Japan has terrific, and improving, competitiveness because there are more than 300 products in which Japan has a global market share above 50%, and 57 where Japan has a 100% share. Many of them are indispensable components or critical materials in a complex final product, like a cell phone. However, the total value of these products does not add up to very much in a $4 trillion economy. The median global sales volume among these 300 products was a tiny $206 million. In fact, Japan is most dominant in niches where total global sales are the smallest. So, while that dominance is great for the companies that produce these must-have items, it does little for either GDP growth or living standards. (See The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future, pgs. 82-83.)

Coming Up in Part II: Inputs Vs. Outputs, Declining Productivity of Japan’s R&D

When we talk of a country’s technological capacity, we must always be careful not to confuse inputs with outputs. Surely, it is meaningful to know how many researchers a country has or the ratio of R&D spending to GDP. But the story is incomplete until we know how many important patents are created by that R&D. And how many of these patents end up yielding lucrative products?

At the same time, we have to look at how many researchers and money it takes to come up with a meaningful invention. Across the rich countries, R&D is producing fewer important patents per researcher and dollar of spending. There are some signs that the decline in research productivity may be worse in Japan than elsewhere.

I’ll explore both of these issues in Part II.

On some days on amazon.co.jp

>in 2023, it ranked a dismal 64th out of 64 economies in “digital agility of companies"

When visiting the linked "World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2023" page, Japan is at 33 not 64. Is there a filter to apply, or a sub-page to visit, something like that?

Thanks for another interesting analyis. Where is the list of the "300 products in which Japan has a global market share above 50%, and 57 where Japan has a 100% share?"