June Wages and Consumer Spending Disappoint Again

Results Put Downward Pressure on Interest Rates and Yen

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/monthly-labour.html

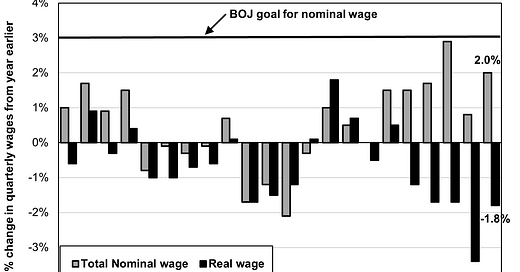

Wages in Japan disappointed again in June, rising less than economists had forecast. Moreover, real wages—wages adjusted for inflation—fell year-on-year for the 15th month in a row (see chart above showing year-on-year changes per quarter). As a result, real consumer spending fell year-on-year for the fourth month in a row, bringing spending during April-June 5% below its 2018 level (see chart below).

Source: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kakei/longtime/zuhyou/season.xls

These results have refuted the hope that the big pay hike in the spring Shunto negotiations between big companies and their unions would lead to a pay hike throughout the economy. That, in turn, means lackluster growth and a longer period before the Bank of Japan (BOJ) will feel confident that healthy 2% demand-led inflation will return to Japan on a sustained basis. The BOJ has repeatedly said that this outcome requires sustained 3% growth in nominal worker pay. Consequently, the BOJ will hold off even longer before letting interest rates rise. As a result, rates on 10-year Japan Government Bonds (JGBs) will not rise as much as the market had expected when the BOJ appeared to announce on July 28th that it would let the rate rise as high as 1%.

Wages Per Hour Sluggish; Minimum Wage Hike To Help 20 Million Workers

There are two ways companies can hike pay. The first and most impactful is raising “base pay,” i.e., wages per regularly scheduled work. The other is increasing overtime work and increasing the semiannual bonuses. The latter can add up to a few months’ pay. The latter are less impactful because there is no assurance that they will last. Overtime work depends on the state of the economy, as do bonuses. By contrast, when base pay is hiked, that is not only permanent but provides a baseline for further hikes. Consequently, workers are more likely to adjust their spending patterns in accordance with the base pay hikes.

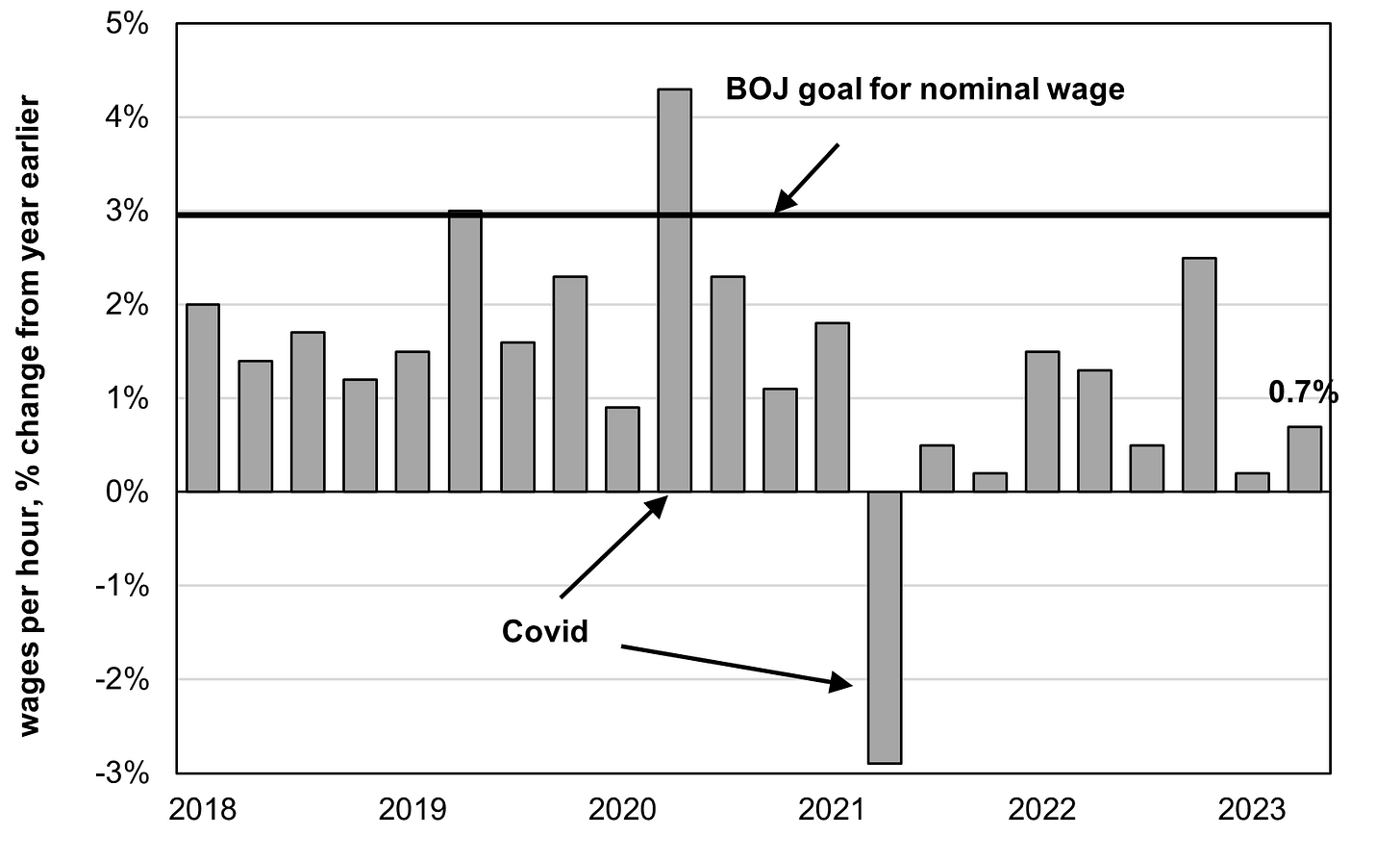

The chart at the top is a measure of total pay in any given month or quarter. In the chart below, by contrast, we can see hikes in base pay. In April-June, the period in which most of the Shunto negotiations’ impact would manifest itself, base pay per hour increased a measly 0.7%. It was not only far from the BOJ’s 3% goal, but also far below the 1.8% average seen during 2018-2019, i.e., prior to Covid. Barring some unlikely occurrence in the next couple of months, this data discredits the wishful thinking that this spring’s Shunto wage negotiations marked a quantum leap in worker pay.

Note: Nominal base pay per hour for regularly scheduled hours, not including overtime or bonuses; the big rise in April-June 2020 and a big dip in April-June 2021 reflected the Covid-caused dip in hours in 2020 and then recovery in 2021.

Fortunately, there is some good news. The government raised the minimum wage for the coming year by ¥41, the biggest hike since records began, thereby raising the minimum to ¥1,002 per hour ($7) on a national average (rates differ by prefecture). The latter was a goal set 13 years ago. The hike, which will go into effect in October will boost pay for 20 million workers who now get below that new minimum, or somewhat above it, according to JP Morgan.

Impact On BOJ Policy, Interest Rates, and The Yen

The BOJ has been quite clear on its strategy, even if it likes to surprise the market when it makes its tactical moves. (The US Fed and European Central Bank do not think such surprises help them.) The BOJ has repeatedly said it will not abandon its ultra-easy monetary policy until the data is clear that healthy 2% demand-led inflation is going to be sustained. Wage data is particularly important. Nominal wages have to rise 3% per year because, given a 1% annual hike in output per worker, costs to employers will rise 2% and they’ll pass those costs onto consumers. Moreover, Governor Kazuo Ueda has said he believes that it’s more harmful to ease too early than too late.

Sometimes, the BOJ makes tweaks to maintain its policy without causing too much stress and, in that effort, it has often confused the market. On July 28th, in a move that surprised 80% of market forecasters, the BOJ announced that, while it wanted the interest rate on the 10-year JGB to go no higher than 0.5%, it would not apply that policy too rigidly; it would not let it go any higher than 1%. The market inferred the BOJ to mean it would not interfere if the rate did indeed go to 1%. Within a couple days, the rate jumped to 0.65% (see chart below). But the BOJ had muddled its message. And so, on August 2nd and 3rd, the BOJ intervened to buy JGBs and send the rate back down again. The JGB closed on August 8th at 0.589% (again see chart below). So, now, market traders don’t know whether the BOJ will allow the rate to hit 1.0%, but not too quickly, or if it wants to keep it closer to 0.5%. But since market players now know that the BOJ is, at the least, not going to tolerate a rapid move upward it rates, the latter will likely be lower in the next few months than they otherwise would have been.

Source: https://www.wsj.com/market-data/quotes/bond/BX/TMBMKJP-10Y

In a move that goes against precedent, Ueda indicated in his July 28th press conference that one reason for the tweak regarding 10-year JGB rates was to moderate “volatility” in the currency markets, a codeword used by the Finance Ministry (MOF) only when quick moves go against the level it would prefer. Ueda’s statement went against precedent because currency policy is under the purview of the MOF, not the BOJ. But four weeks before the BOJ moved, the MOF had threatened to intervene in the currency markets when the yen weakened to nearly ¥145/$ (see chart below). In the next few weeks, the yen did weaken even though the threat was not carried out. It is not known whether the MOF and BOJ coordinated on the BOJ’s JGB tweak. By the way, ¥145/$ is also the rate at which the MOF heavily intervened last fall to little avail.

In any case, the gambit does not seem to have worked, at least not so far. The yen has weakened again and, as I write this, the yen stands at 144.44, closer to the level at which the MOF had previously threatened to intervene (see chart below). One reason is that the yen/$ rate depends on the gap between American and Japanese rates. A more rapid rise in Japanese rates would have narrowed the gap and thus given the yen a boost. Now that this expectation is postpone, this suggests the yen will be a bit weaker than it might otherwise have been.

Some European subscribers asked me about the yen/euro rate. Arithmetically, of course, the yen/euro rate equals the yen/$ rate divided by the euro/$ rate. The question is whether the number or denominator is more influential. As it turns out, the yen/euro rate is better predicted by changes in the yen/$ rate. So, those interested in the yen/euro rate should find the discussion of yen/$ moves helpful.

It is sometimes said that Japan is experiencing a labour shortage (or at least tightening). In such circumstances, one might expect that workers would move to better paid jobs and force employers to raise wages in response. (This is certainly what has been happening recently in the UK - one of the top news stories this morning is that basic pay growth has risen to 7.8%.) But given the anaemic pay growth in Japan, this doesn't seem to be happening there. I wonder why not? Is it because the relative lack of external labour markets prevents it? In the case of precarious workers (agency etc), is there no labour shortage in this sector that might force up wages? What is going on?