Why Kishida Retreated From “New Form of Capitalism”

Can It Be Resurrected In “Five-Year Plan” Promised for December?

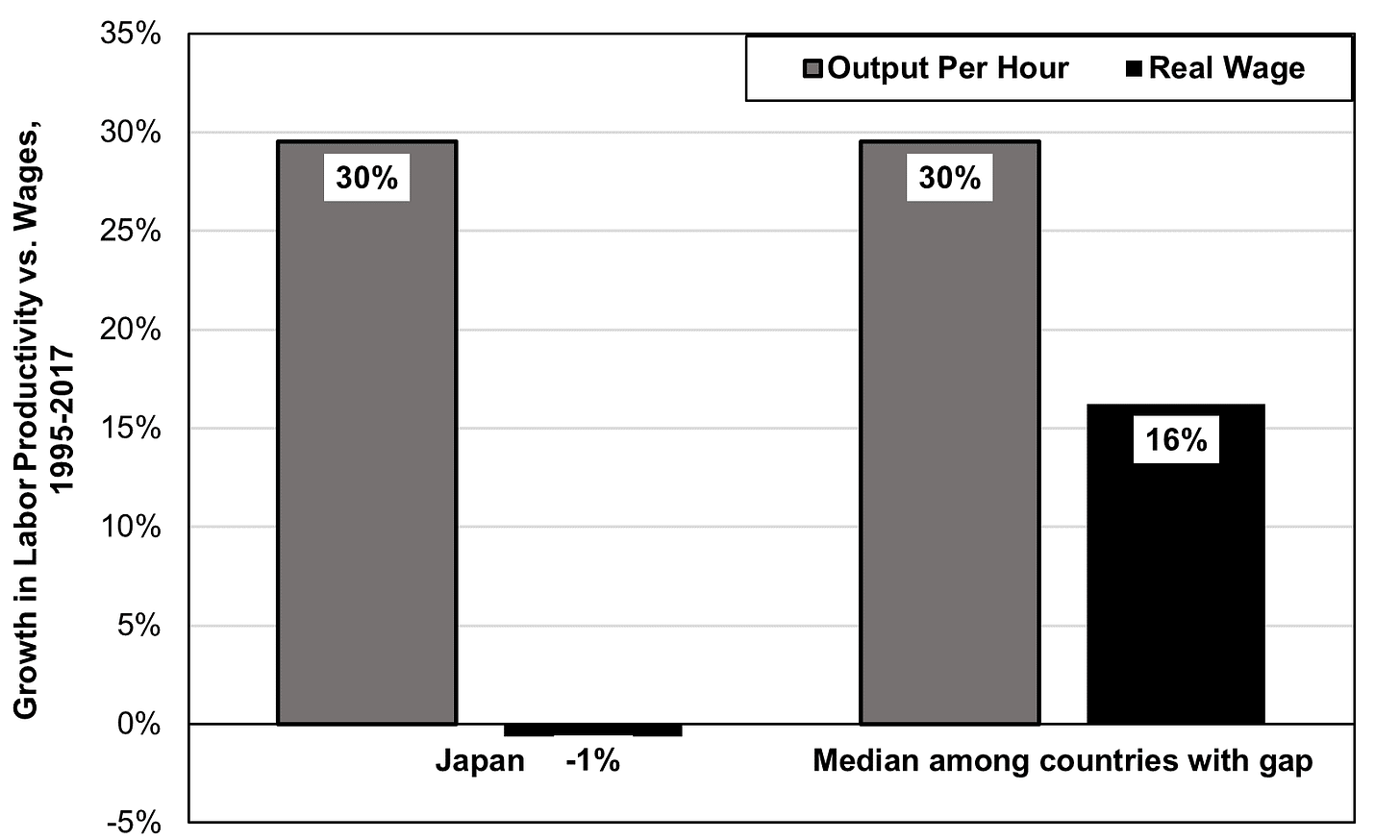

(For details behind the chart, see Why Wages Slowed More In Japan Than Elsewhere)

For six long months, the Kishida administration, aided by reform-minded outsiders from academia and new companies, toiled to translate Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s mantra of a “new form of capitalism” into concrete policies. The rather hollow end product approved by the Cabinet on June 7th was a big disappointment to many of those participants.

When it came to the foundational principle—that good growth and a more equal distribution of income needed each other—Kishida simply caved to critics in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and financial markets who falsely accused him of promoting socialism. It is not socialism to say, as Kishida did, “If the fruits of growth are not redistributed, consumption and demand will not increase.” It is a longstanding verdict of standard macroeconomics.

Because of Kishida’s retreat, the policy document is top-heavy with rhetoric about a “virtuous cycle of growth and distribution,” but very weak on any substantive measures to bring it about. Kishida’s surrender began just after his inauguration due to the so-called “Kishida shock” when stock prices fell in response to his call for higher capital gains taxes on those earning more than ¥100 million ($745,000) per year. He withdrew the proposal. The backpedaling continued, said a participant in the Council’s deliberations, when Kishida decided that he could not afford to offend Keidanren, the big business federation, on the eve of the July Upper House election. Kishida needs a solid victory to consolidate his clout within the LDP.

That left Kishida with nothing more than a rehash of failed measures laid down by predecessors like Shinzo Abe. On wages, for example, Kishida repeated past futile requests for companies to raise wages by 3% per year. He also repeated the longstanding goal of attaining a minimum wage of ¥1,000 ($7.40) per hour but gave no timeframe for achieving that goal. He proposed giving somewhat larger temporary tax breaks to companies that raise wages by a certain increment, even though history has shown that companies do not grant permanent wage hikes in return for temporary tax benefits. He promised wage hikes for certain people employed by the government, like nurses.

When it came to a key component of the growth strategy—a tenfold increase over the next five years in the number of startup companies—the results were even more frustrating to the reformers. A team of officials and outsiders under the aegis of the Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation produced a first-rate analysis of the key issues that keep Japan’s startup rate so low—even though they left out some vital issues like banking. Just a few examples are tax incentives for “angels” that provide early-stage funding, government procurement that gives startups much-needed revenue and credibility, and the use of stock options to enable cash-strapped new companies to attract top talent. However, the final document studiously avoided specific proposals on these issues. (For a detailed discussion of these issues see my previous post, How To Restore Japan As A Startup Nation, as well as the link to longer pieces at https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/591483 in Japanese or https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/592735 in English.)

When some participants expressed frustration, they were told, “Wait until after the Upper House elections.” The Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office) feared positing specific remedies, particularly those involving taxes or labor issues. Doing so might have brought to light controversies among Ministries and interest groups, and that could hurt the LDP in the election. The Ministry of Finance (MOF), for example, has repeatedly objected to the kind of tax breaks needed to nurture new startups. The Kantei promised that, by year’s end, it would present a “five-year plan” loaded with powerful specifics. However, conversations with several participants revealed lots of hope, but little confidence, that the plan would be truly substantial. One official worried that Kishida would spend his limited political capital on a hike in defense spending and not have enough capital left for controversial economic measures. Several stressed that Kishida’s own faction within the LDP is relatively small and he therefore could not afford to alienate the much stronger, and more conservative, factions led by Abe and former Finance Minister Taro Aso.

Kishida’s leadership style adds to the backsliding. For one thing, noted a couple sources, while Kishida has long been interested in wage issues he has never really thought out in detail what it would take to create “a new form of capitalism.” Moreover, Kishida is not the kind of Prime Minister who can operate in a top-down basis in imposing on the LDP and bureaucracy a few key priorities, as Abe did on collective security, and Yoshihide Suga did regarding decarbonization. Instead, Kishida is a consensus-builder who styles himself a “good listener.” When various power centers differ, he tries to get them to work out a compromise rather than imposing a solution himself. That style may be productive in some situations, but it cannot produce the big economic “course correction” that Kishida claims to be making.

Toyo Keizai will publish in Japanese and English my analysis of Kishida’s retreat as well as some proposals on what could be done to catalyze a virtuous cycle of growth and distribution. I will post that when it appears.

Surely that is now standard macroeconomics as a result of socialists and social democrats in general pushing for it to become standard. And that it was not so up until the 1920s and 1930s in many countries. For example the 'Share Our Wealth Society’ of Louisiana Senator Huey P. Long, who in 1935 was assassinated for his plan to, indeed, share the wealth. Or the capitalist and conservative, The Liberty League, which also attacked the New Deal as a form of socialism, using weak points very similar to those being made now.

So, essentially, plans to redistribute wealth ARE from the left, and its a very good thing too... we would be in a far worse world now if it was not for all these left wing folk pushing for that since the early 19thC. Most of what we like about society is largely the result of previous socialists, unionist and liberals pushing for it. Such a low cost national health system or pensions for those injured in war. And almost all these things were strongly resisted by capitalists.

And this watered down policy of the LDP is a good example of how its very difficult for capitalists to reform capitalism to the extent that is no longer an abusive system. It's like asking school bullies to police other school bullies.

Nowadays the common push in many countries for 'a new form of capitalism' is, i think, a positive sign. At root it shows that more and more people see that capitalism doesnt work well. The problem is a lack of vision and courage to take the action that will actually establish a decent system for all. And the powers against fundamental change are still strong. Still, since the various wishy washy reforms are very unlikely to make much difference we may yet see a majority of people come to think what we really need is to 'reform capitalism completely out of existence', and organise ourselves in a different and better system. Which is possible.