Will Kuroda Blink This Week?

BOJ Has Spent 5% of GDP In Flailing Effort To Block Interest Rate Rise

Source: MOF at https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/jgbs/reference/interest_rate/index.htm

The market is upping the pressure on Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda to raise interest rates. The BOJ, in response, has spent 5% of GDP in so-far-unsuccessful efforts to keep interest rates down through massive purchases of Japan Government Bonds (JGBs). Despite this, rates are already above the maximum level the BOJ had said it would allow.

Consequently, there is a growing view that, sooner or later, the BOJ will have to yield. Some investors say the BOJ will make another “tweak” in raising rates as early as this coming Wednesday when the BOJ Policy Board finishes a two-day meeting. Others say it will take until March. Others think nothing will happen until after a new Governor replaces Kuroda in April. Still others believe the BOJ will move back to controlling only overnight rates and let the market determine longer-term rates. And, finally, there are those who think the BOJ can win, though not as many as a couple of months ago.

Even if the BOJ does decide on another “tweak,” some traders suggest it may do so in a surprise move, as it did on December 20.

BOJ Spent 5% of GDP In Losing Effort To Hold Down Rates

On December 20, the BOJ made its first tactical retreat when it raised the maximum rate on 10-year JGBs from 0.25% to 0.5%. However, it had spent a lot of money in its futile effort to hold the line at 0.25% and has continued to spend money in its equally unsuccessful effort to hold the new line in the sand. During December, the BOJ spent ¥17 trillion, or 3% of GDP. On January 12 and 13, it spent another ¥10 trillion, or 2% of GDP, a daily record. As a result, the BOJ probably owns around 55% of all JGBs.

This money is not working. The 10-year yield rose to 0.554% early Friday morning in Tokyo before settling back to 0.506%. And 8-year and 9-year bonds are fluctuating around an even higher level: 0.6% to 0.7% (see chart at the top).

The reason it’s not working is that, for traders, the risk is one-sided. It’s almost certain that the BOJ is not going to lower rates unless Japan’s GDP suffers an unexpected slowdown. So, if they sell JGBs “short” to the BOJ and the BOJ is successful in keeping rates at today’s levels, they will have lost nothing. On the other hand, if interest rates do rise, that means that the price of existing JGBs falls. Hence, these traders will make big profits. Such one-sided risk creates a big incentive to make the bet. (“Selling short” means selling a security you do not yet own in anticipation that its price will fall, and then buying it later (“covering your short”) when the price is lower. If, as you expected, the price does fall, you can make huge profits.)

The BOJ’s problem is not that it will run out of money. It can create all it wants. The problem is that its efforts are causing adverse side effects in the corporate bond market, something the BOJ does not want to see. Partly, this is due to the return of “the kink” in the “yield curve,” the line in the top chart showing the interest rate at various maturities. Normally, the longer the maturity, the higher the yield. But, these days, the rate on 8 and 9-year JGBs is higher than on 10-year bonds. That’s because most of the BOJ JGB-buying targets the 10-year bond. For technical reasons, a kink in the JGB yield curves causes serious distortions in the corporate bond market. A similar kink in December helped compel the BOJ to make its tactical retreat on December 20. A discussion of such side effects is on the agenda for this week’s BOJ Board meeting.

In any case, the steepness of the yield curve has increased greatly since the beginning of the year and even more so since December 20th. This is a de facto tightening, contrary to the BOJ’s intention. That is likely to raise the interest rates that banks charge on loans. As of November, 37% of all loans charged less than 0.5% interest, and half of these loans charged less than 0.25% (see chart below). Rates are likely to rise somewhat, putting a burden on companies with scarce profits. How much lending rates rise will depend on supply/demand conditions in the loan market.

Source: Bank of Japan

The Role Of Inflation

The one thing that could help the BOJ’s efforts is a decline in Japan’s inflation similar to the decline the US is already enjoying. But so far that has not happened. On the contrary, Japan-style “core” inflation (all prices except fresh food) rose 4% year-on-year in Tokyo in December, the most in 40 years. A similar rise is expected when nationwide figures are released following the BOJ decision.

The BOJ has consistently predicted that inflation would slow down this year as global prices for food and energy retreat. In its October Outlook report, the BOJ predicted that, after rising 2.9% in fiscal 2022, which ends in March, inflation would slow to 1.6% in fiscal 2023 and 2004. This is below the BOJ’s 2% target rate. A telling sign for future BOJ policy will be the prediction to be made in the Outlook report coming out of this week’s Board meeting.

What All This Means For The Yen

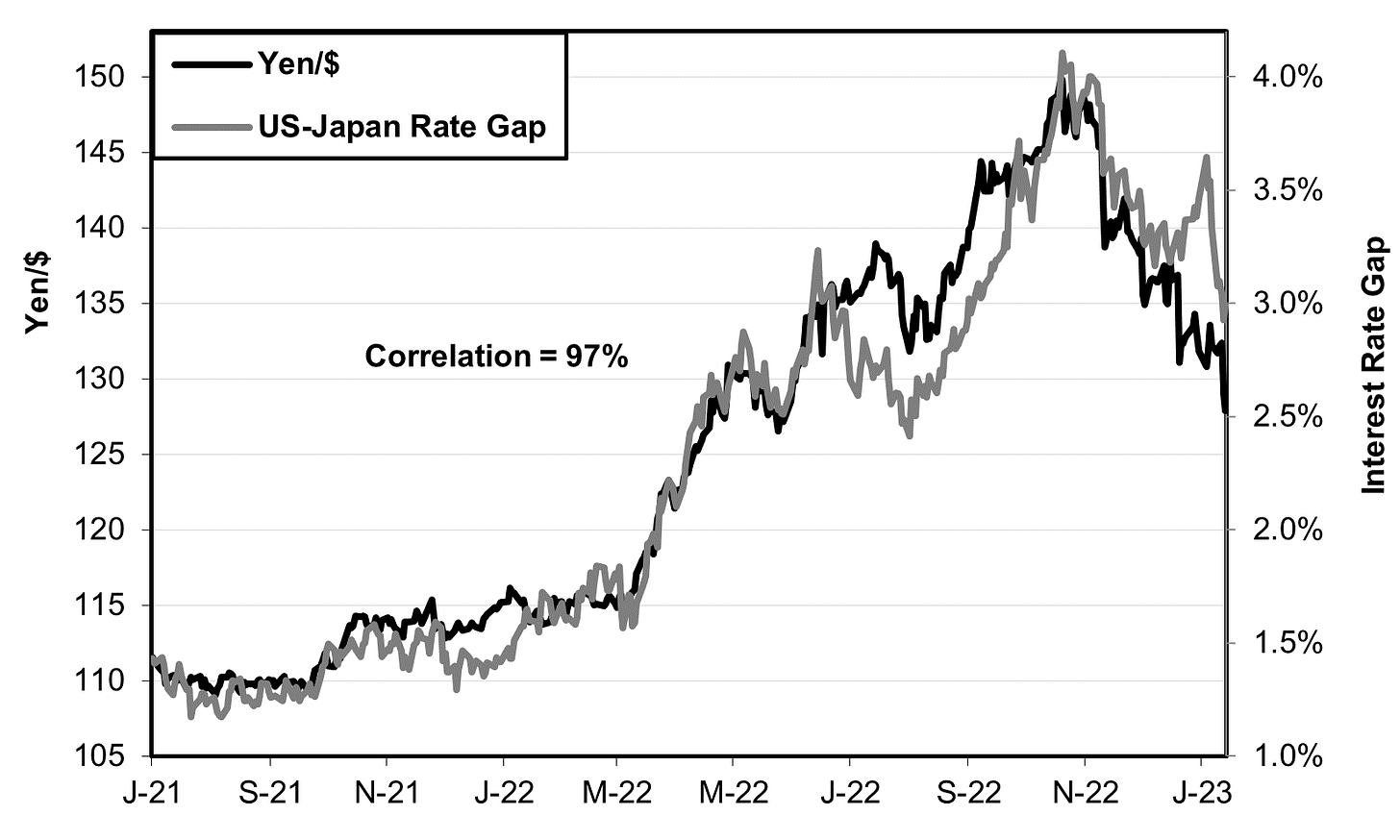

As we’ve repeatedly emphasized, the biggest short-term factor currently influencing the ¥/$ rate is the gap between 10-year government bond rates in the US and Japan. Not surprisingly, as the gap lessened—due to falling US rates and rising Japanese rates—the yen regained some of its losses (see chart below).

Source: US Fed, Wall Street Journal

As the chart shows, the yen is now becoming stronger somewhat ahead of the change in the rate gap. The reason is that the yen moves, not only in response to the current rate gap, but also in anticipation of future rate gaps. That anticipation can be significant during times when a big change in rates is expected, in this case, a rise in Japanese rates.

This pleases the Kishida administration since 90% of Japan’s inflation comes from the rise in prices of import-intensive items like food and energy. A weaker yen means even higher prices and inflation is a factor in Kishida’s weak approval ratings.

However, there is a limit to how much the yen can recover. Japan is fundamentally less competitive in international trade than it used to be. Its electronics companies, which used to run big trade surpluses, now run trade deficits. Its auto companies remain very competitive. However, the automakers now rely on overseas production, not exports, for 85% of their overseas sales.

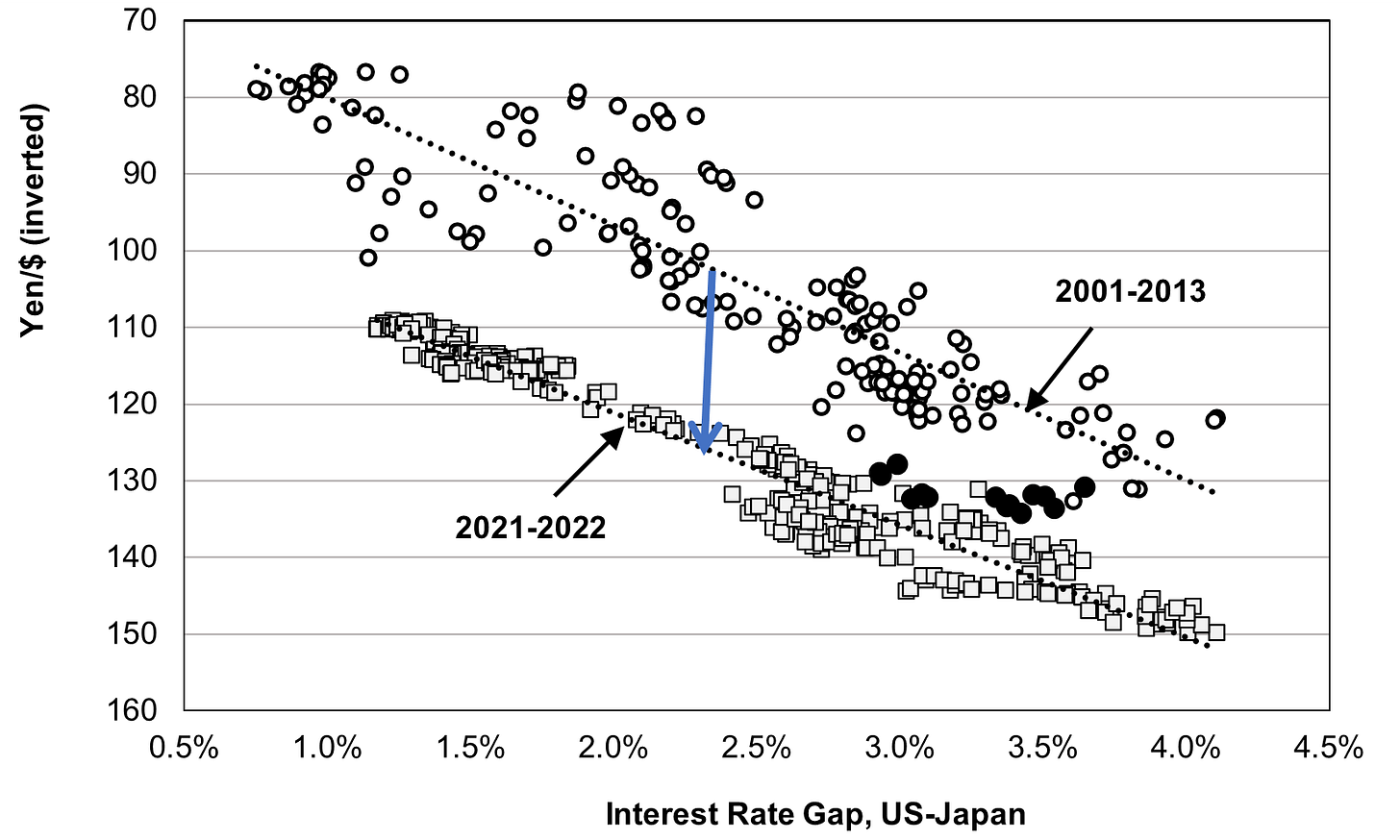

A nation that has become less competitive tends to suffer a weaker currency and that is the case for Japan. For any given gap between US and Japanese interest rates, the yen is about 20 points weaker these days than it was back in 2000-2013 (see chart below).

Source: Author calculation based on data from US Fed, Wall Street Journal

I will be watching closely to see whether anything changes in this pattern. The black dots in the chart show the linkage between the rate gap and the yen’s value since December 20. At today’s situation, with a rate gap of around 3%, the black dots are a lot closer to the 2021-22 trend line than the 2001-13 trend line.

The bottom line is that, even as the yen recovers from the nadir of ¥150/$, it will most likely remain a lot weaker than it has been during most of the past decade. That means Japanese households will continue to pay high prices for food and companies, as well as households, will continue paying high prices for energy. This is not a good sign for Japanese growth or well-being.

"For technical reasons, a kink in the JGB yield curves causes serious distortions in the corporate bond market."

Could you maybe elaborate on this or share a link with the explanation? I would be curious about the mechanism behind that.

This situation is not dissimilar to the issues in the US. The US has a federal government that has spent like crazy for the past couple of years -- this has caused significant inflation and the central bank has increased interest rates to pull that cash out of the system. Japan has an antiquated set of laws, rules and regulations that limit the opportunities of businesses and the BoJ is trying to offset these issues.

Richard has correctly pointed out that this is a very difficult problem to fix... especially if it is only the BoJ that is trying to do the heavy lifting. We aren't going to see prosperity return to Japan without significant changes in the legal system and regulation. Japan's issue are very long term.