METI's “2025 Digital Cliff,” Part II

Shortfall in STEM Students, Low Pay for ICT Pros

Source: OECD Education At A Glance 2011 Indicator A4.6 at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932460192

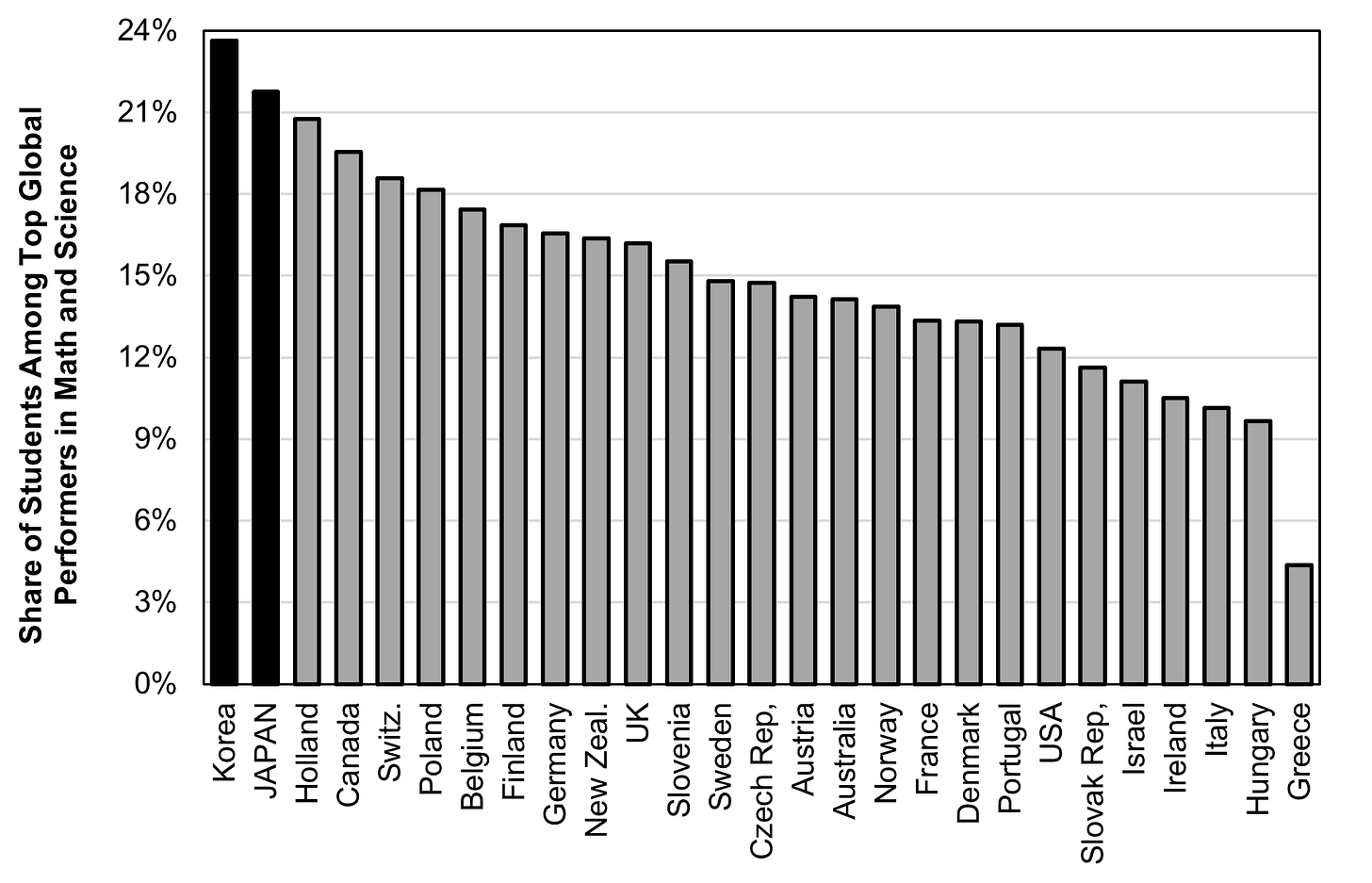

As early as high school begin the roots of Japan’s big shortage of professionals in information and communications technology (ICT), which is projected to hit somewhere between 450,000 and 800,000 by 2030. Even though Japan scores just below Korea in the share of high school students who rank among the top global performers in science and math tests (see chart below), Japan prepares its students poorly for working in ICT occupations.

Source: OECD PISA 2018 results, Table II.B1.8.22 at https://doi.org/10.1787/888934038723

Note: Top performers refer to students who achieve at least Level 2 in all three core domains and at Level 5 in mathematics and/or science

In several important categories of ICT training, Japan scores below the OECD average and, in some, Japan comes in last out of 29 countries. It ranks lowest in vital areas like teachers’ own ICT skills, their ability to teach such topics, resources to train these teachers, and even something so basic as having enough equipment and online learning platforms (see chart below).

Source: Source: OECD PISA 2018 results, Table V.B1.5.15 at https://doi.org/10.1787/888934132260

How is this possible? One big reason, explained Kan Suzuki, an advisor to the government on education reform, is that digital skills are not included in university entrance exams. So, high school teachers feel little need to teach them (minute 43:05 to 45:00 at the Japan Zoominar). It is progress that, beginning in 2025, according to Suzuki, the entrance exams will include ICT-related questions. But that still leaves the question: who will teach the teachers? And how long will that take?

No wonder, then, that Japan comes in below average in the share of high school students who expect to have a career in ICT (see chart).

Source: OECD Table II.B1.8.19 at https://doi.org/10.1787/888934038723

It’s not that Japanese high schoolers are uninterested in using computers and the Internet in their leisure time. Among high school boys, Japan ranks number one in using the Internet to search for information on a particular topic several times a day, and Japan’s girls come in second among OECD girls. Japanese boys also rank number one in single-player online games. On the other hand, these boys score at, or near, the bottom on other activities, such as multi-player online games or uploading their own content. Moreover, while some of these activities may contribute to a desire to seek a career in ICT and to develop the necessary skills to do that, they do not necessarily do so.

Dearth of Science and Engineering Students And Careers

Japan does even worse—third from the bottom—in the share of students who foresee having a career, not just in ICT, but in any area of science or engineering (see chart).

Source: OECD Table II.B1.8.19 at https://doi.org/10.1787/888934038723

What’s even more remarkable is that Japan’s top performers on the math and science tests come in dead last in the share who foresee themselves working in science or engineering. It also ranks last when only top-performing boys are considered.

Source: OECD Table II.B1.8.22 at https://doi.org/10.1787/888934038723

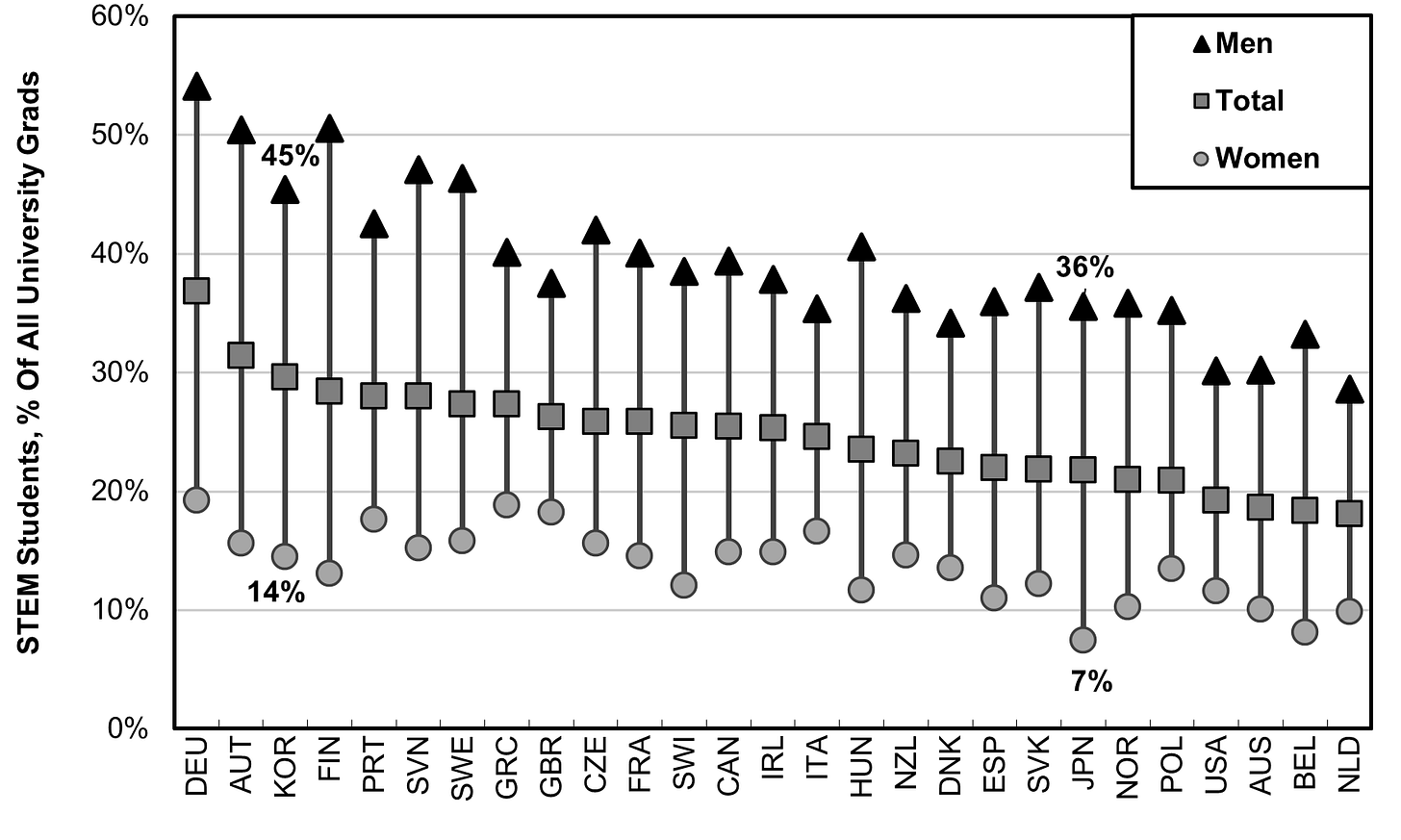

Low Level of STEM Major and STEM-Trained Employees

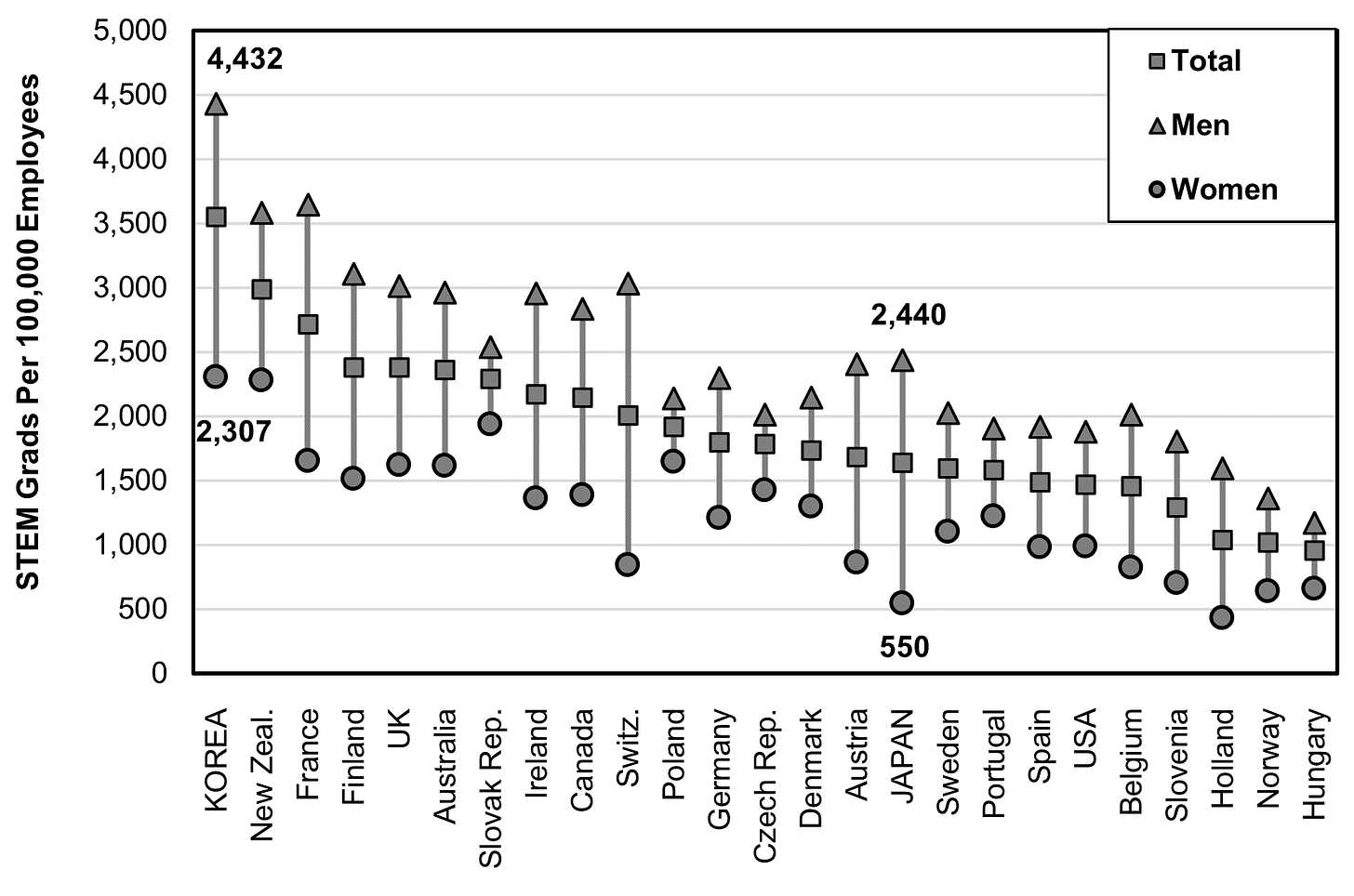

Low pay and other hurdles—to be detailed below—lessen the allure for careers in ICT or other STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, or Math) occupations. So, fewer university students see the benefit of majoring in a STEM subject. Japan ranks 22nd out of 27 countries in the share of university graduates who majored in a STEM course. Among women, Japan comes in last in the share of STEM graduates. But it also ranks low among men, at 21st. By contrast, Korea ranks third among all students and in the middle of the pack among women (see chart below).

Source: Figure 2.24 OECD Economic Survey of Japan 2021 at https://stat.link/snkrg6

The result of all this is that Japan has fewer STEM grads to fill jobs. In fact, it ranks below average in the number of STEM graduates per 100,000 employees in all business sectors, just 16th out of 25 countries (see chart at the top of the blog). Japan comes in second to last among women and 11th among men. By contrast, Korea ranks not only number one at 3,555 in total, but also first in the number of men and the number of women. In fact, the number of female STEM grads per 100,000 employees in Korea is almost as high as the number of males in Japan. This is just one of the major reasons Korea has surpassed Japan in per capita real GDP.

Pay Is Low For Hard Work

Low pay contributes to Japan’s shortfall in both STEM and ICT professionals. Companies complain that they cannot hire as many specialists as they like. The job-to-applicant ratio is 10:1 in ICT, compared to 2.8 for marketing jobs and 0.4 for sales positions. Yet, most companies are unwilling to offer the pay required to lure more of Japan’s smart students into the field. That’s largely because, in most companies, seniority counts more than occupation in determining pay. Attempts to alter this practice have run into resistance from unions as well as non-union workers who, based on experience, see such changes as attempts to lower the pay of workers without such special skills.

In 2021, the average annual income of a Japanese ICT staffer was just ¥4.38 million ($34,466), down 4% from 2019. That was 2% below the median salary in Japan, whereas in the US and China, ICT salaries are 8-10% above the median. Averages understate the gap because they hide the big differentials in American and European pay for the most highly skilled ICT pros and lower level technicians.

Meanwhile, to be qualified to get even a basic job ICT in Japan, one must often attend a three-to-six-month course at a vocational school at a cost of ¥300-600,000 ($2,300 to $4,600). Moreover, lab fees and other fees mean science majors pay more than others. Many students decide it’s not worth it to spend the time and money if it doesn’t boost their pay.

It’s hard to get an apples-to-apples comparison in salaries between Japan and other countries since sources give different numbers as a result of the wide variety of occupations within the ICT field. But all sources show that pay is low compared to salaries in many other places. For example, the median pay for software developers in Japan was $100,000 in Japan, less than in Beijing or Singapore. A cybersecurity consultant is likely to earn no more than $120,000 in Japan, compared to $228,000 in Hong Kong and $181,000 in Singapore. One survey says 65% of ICT staffers earn ¥3.9-to-5.4 million ($30,000-to-$41,000) per year, while just 5% earn more than ¥6.15 million ($47,000), and a sliver can earn as much as ¥10 million ($76,000). Another survey says that, in recent years when the yen was valued at around 100/$, an IT technician in Japan earned an average of $42,400, which put it at the 18th highest salary in the world, and about half the US level.

Some large companies, like Fujitsu and NTT Data, are reportedly becoming more flexible in their pay for ICT workers at the highest skill level and paying more than $100,000 per year. So far, they remain an exception. One can only hope they’ll become harbingers.

In the concluding part III, I’ll discuss some of the remedies being discussed.

This sequence has been riveting. Looking forward to part 3.

"Yet, most companies are unwilling to offer the pay required to lure more of Japan’s smart students into the field. That’s largely because, in most companies, seniority counts more than occupation in determining pay. Attempts to alter this practice have run into resistance from unions as well as non-union workers who, based on experience, see such changes as attempts to lower the pay of workers without such special skills."

So basically the two major issues blocking this are (i) the 年功序列 system; and (ii) a culture of wanting to get promoted into higher-paying management positions which are less technical (i.e. the "real work" is done by harder working, lower paid juniors, just like ものづくり職人 are respected for their art but ultimately not well paid)

I cannot see how this will change given the mass consent required to change, and resistance to giving special treatment to certain groups of people