Mini-Post: December Headline Inflation at 2.1%; Ex-Food & Energy At 1.5%

Stagflation Still Posing Dilemmas for BOJ

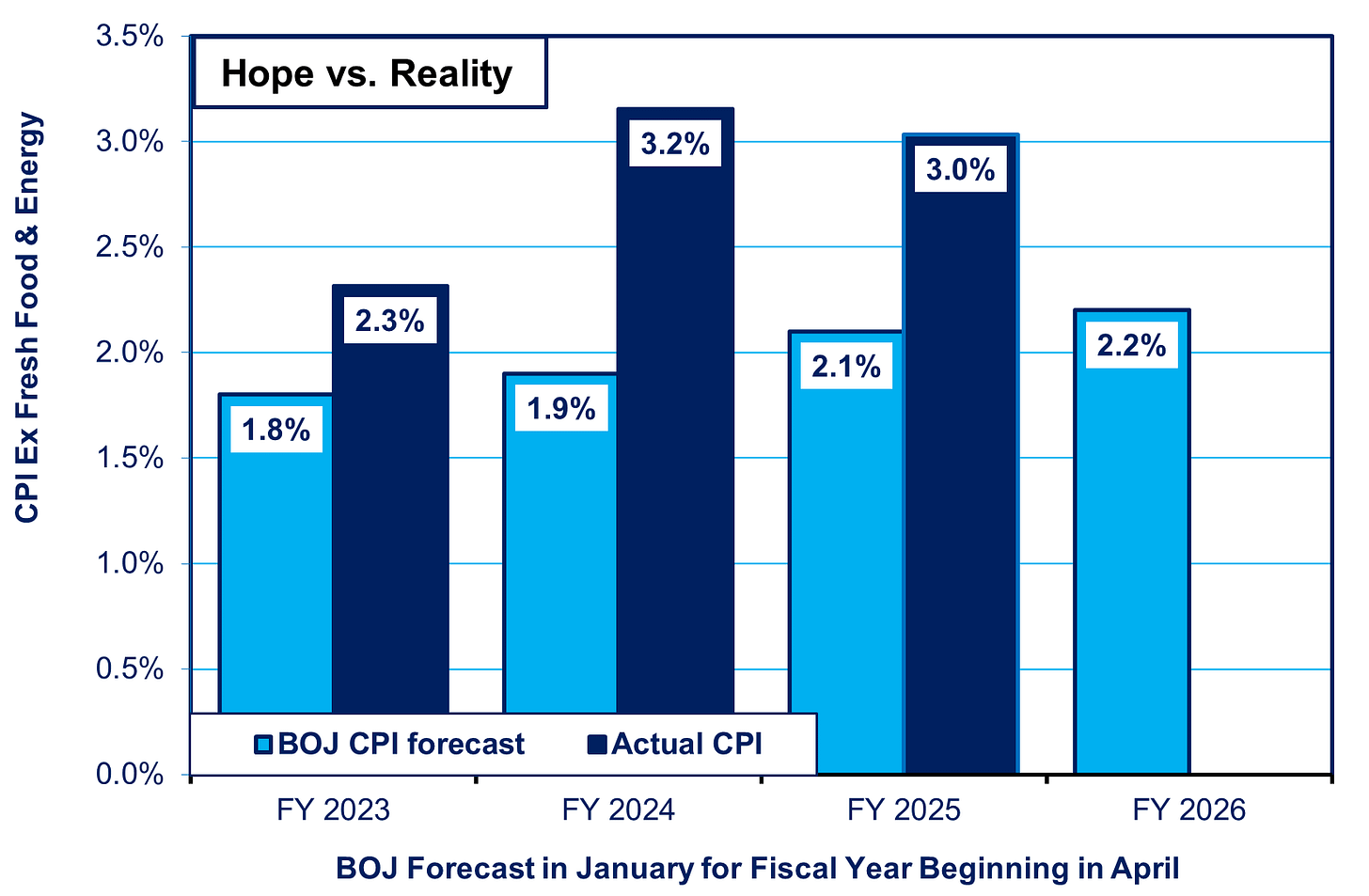

Source: Bank of Japan’s “Outlook For Economic Activity and Prices” and https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000032103932&fileKind=1 for inflation; fiscal 2005 is based on April-December; see text for further explanation

FLASH: This is the second in my new series of miniposts, which will soon be available only to paid subscribers and to those who contribute a substantial amount via “buy me a coffee.” This one is coming out today in response to just-released inflation data. My regular post, available to all, will come out later in the week. For a few more times, I will make these miniposts available to all subscribers so you can see what you’ll get if you upgrade.

At its meeting last week, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) once again decided to wait for more evidence before giving overnight interest rates another ratchet upwards. Stagflation—the combination of a weak real economy and rising prices—continues to create policy dilemmas, as I discussed recently.

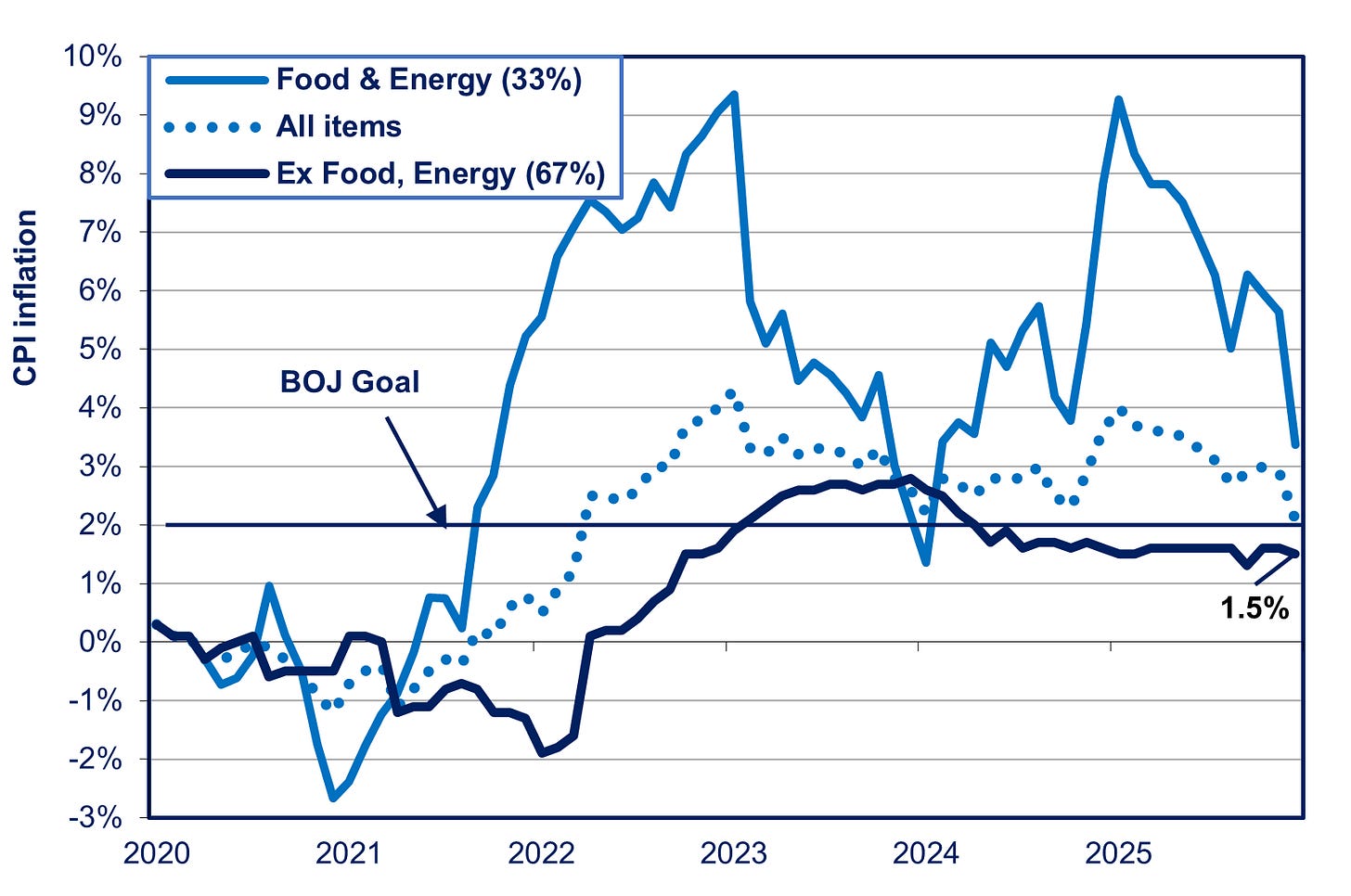

The inflation data released Friday shows the same pattern it has shown for months.

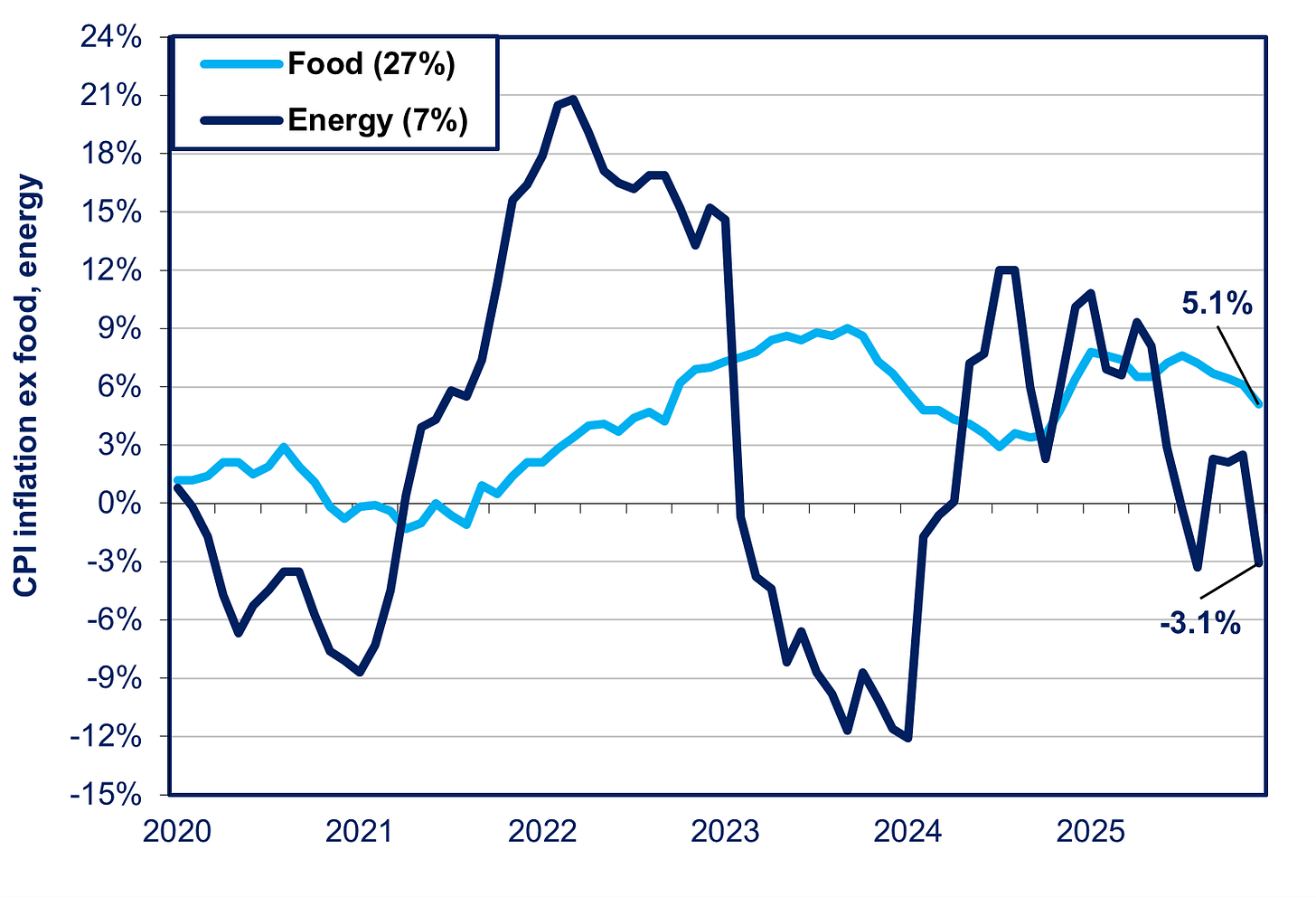

On the one hand, there has been a continued decrease in “bad inflation,” i.e., the unhealthy price shock afflicting the economy via price hikes in import-intensive food and energy (see the first of the two charts below). In December, the price of food, which comprises 27% of people’s budgets, rose 5.1% from the year before, while energy prices fell 3.1% (see the second of these two charts below). The symbolically and politically important rice inflation was 31% in December. It is regarded as “bad inflation” because it amounts to a transfer of wealth to foreign countries. It hurts growth by reducing real wages and raising costs for small- and medium-sized enterprises. It is determined by both global prices and the yen’s purchasing power. Food and energy accounted for 68% of the entire increase in prices over the past two years, and 74% over the past five years.

On the other hand, healthy inflation—price hikes caused by increases in wages and domestic demand—remains substantially below the BOJ’s 2% target. It was 1.5% in December. It has averaged 1.6% ever since mid-2024, with no sign of rising (see again the chart above with the dark line showing “ex food and energy”).

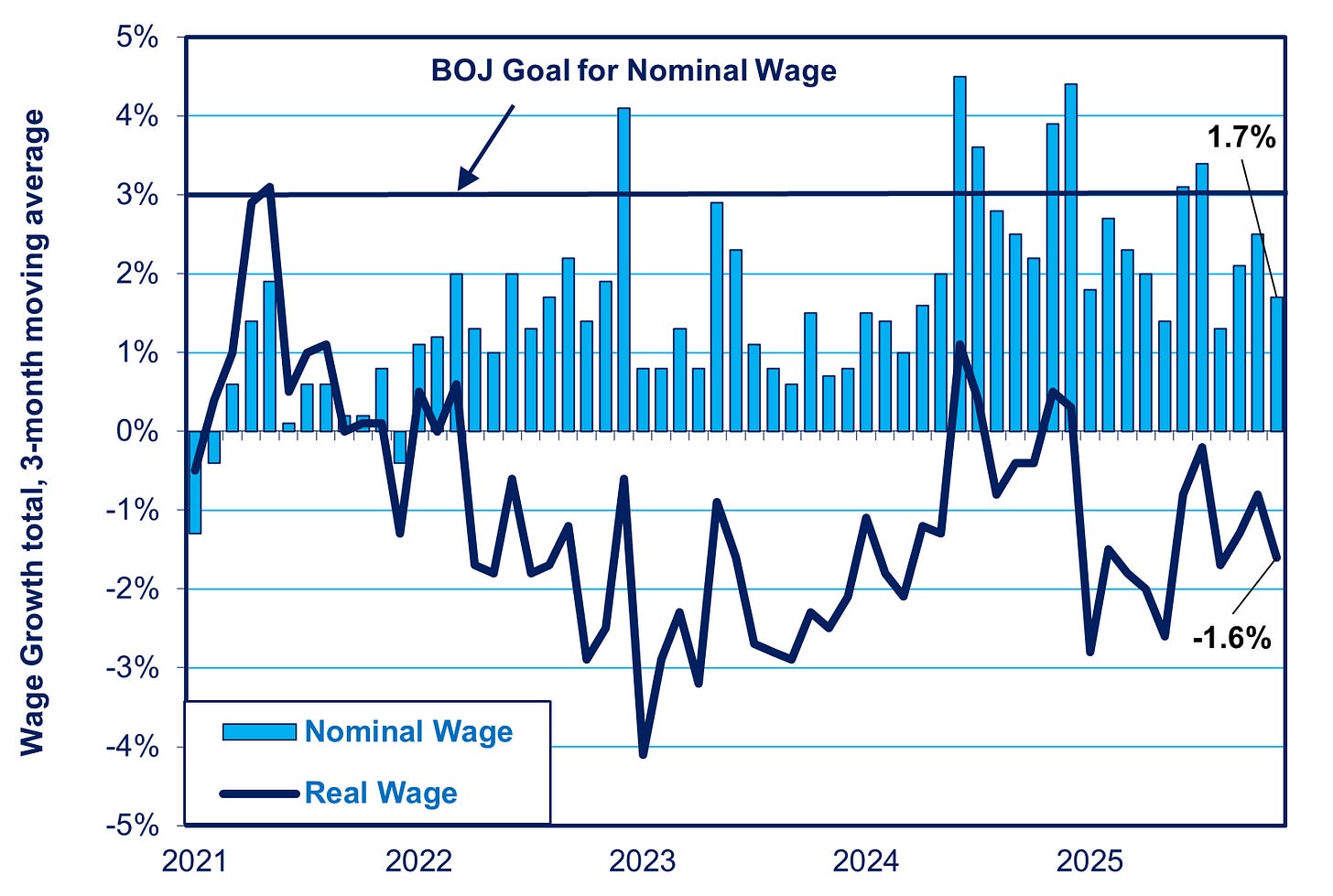

For the past decade, the BOJ has been saying that nominal wages need to rise 3% a year in order to produce 2% inflation led by private domestic demand. However, as of November, nominal wages remain far below 3% and real wages keep falling in the face of inflation (see chart below). That has suppressed the real consumer demand necessary for healthy inflation.

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/monthly-labour.html

All of this creates a real dilemma for the BOJ. Should it raise interest rates to fight its definition of “core inflation”—all items except fresh food and energy—which stood at 2.9% in December? Or, should it keep rates down to help stimulate consumer spending and business investment? See this post again.

One final note. The BOJ keeps saying it expects consumer inflation to settle at its 2% target within one or two years at most, and it keeps saying it’s getting close to the target. But as far as we can tell, the BOJ feels obliged to put out this forecast lest it appear to be telling the market that its policy is failing. Every January for the past four years, it has predicted that inflation excluding fresh food and energy would be around 2% in the fiscal year beginning three months later in April. Not once has the actual result come close. It has made the same forecast this year, and we’ll see what happens (see the chart at the top). But its forecast should be seen more as hope than expectation.

Support the Blog

If you feel you’ve gained insight from this blog, ever restacked it, if you ever subscribed to my previous publication, The Oriental Economist Report, and certainly, if you or your firm have gained insights that helped guide your investments, please support the blog with a subscription or by “buying me a cup of coffee.” You can buy a cup or two on a one-time basis, or once a year, or once a month.

As several economists, including Ryutaro Kono, have argued, the BOJ’s assumption that managing inflation expectations will change norms and automatically stimulate consumption and investment may now warrant closer scrutiny. In Japan, where wages and employment structures remain highly rigid, it is far from clear that expectation formation translates into behavior in the way theory predicts.

Rather, the core issue may be that Japanese firms continue to post record profits while failing to pass sufficient value added on to wages. In that sense, the 2% inflation target—originally a policy tool—appears to have become an end in itself.

While it is understandable that the BOJ cannot easily admit past policy failures given market sensitivities, this is precisely why a prudent course correction from the political side, following the recent election and while respecting central bank independence, would be welcome.