The Myth of Japan’s Missing Millionaires? Part 1

Both Too Few And Too Many Millionaires Hurt Growth

Source: https://wid.world/data/

It is commonly believed that Japan has way too few millionaires. In a recent discussion on LinkedIn, a few expatriates working in Japan asserted that the reason was cultural: Japan prioritized stability over allowing people to accumulate wealth. This, they said, was enforced by income taxes that penalized high earners. Before studying the data, I, too, presumed that millionaires were too scarce, but ascribed it to a different reason: pre-tax incomes that were too low for the very skilled, so they could not invest enough to accumulate serious wealth. As it turns out, the belief is wrong. Japan does not have a dearth of millionaires compared to other wealthy countries (although its pre-tax incomes for the highly skilled are too low).

Moreover, prior to the lost decades, Japan actually had a higher percentage of rich and super-rich than most other rich countries (details below). So much for the cultural argument. The misperception about wealth arose during the lost decades, when wealth in Japan flat-lined while it continued to grow elsewhere. So, in relative terms, Japan fell behind.

However, in recent years, as stock and real estate prices recovered, wealth has followed. A recent Nomura Research Institute report showed that, among 1.5 million households with ¥100 to ¥500 million in wealth ($1-5 million in Purchasing Power Parity* terms), total wealth more than doubled over the past decade to a total of ¥221 million per household ($2.2 million PPP). Among the 90,000 richest of the rich households, with more than ¥500 million in assets, wealth tripled during the last decade to an average of ¥1.5 billion ($15 million PPP).

*(PPP is the exchange rate for a currency that means X number of yen, Euros, or Taiwanese dollars, and one US dollar can each buy the same amount of goods and services. In 2024, the PPP value of the yen was ¥99/$. Some sources, like Wikipedia, count millionaires in market value terms. However, this means that, without anything changing in Japan, the number of millionaires in such a list can move up and down depending on whether the yen is at ¥125 or ¥160. To see why PPP can differ from market value, see this post.)

Bloomberg observed, “Real wages only grew in three of the 13 years through 2023. Meanwhile, in 2023, the top 3% of Japan’s richest households held 26% of the country’s household net assets.”

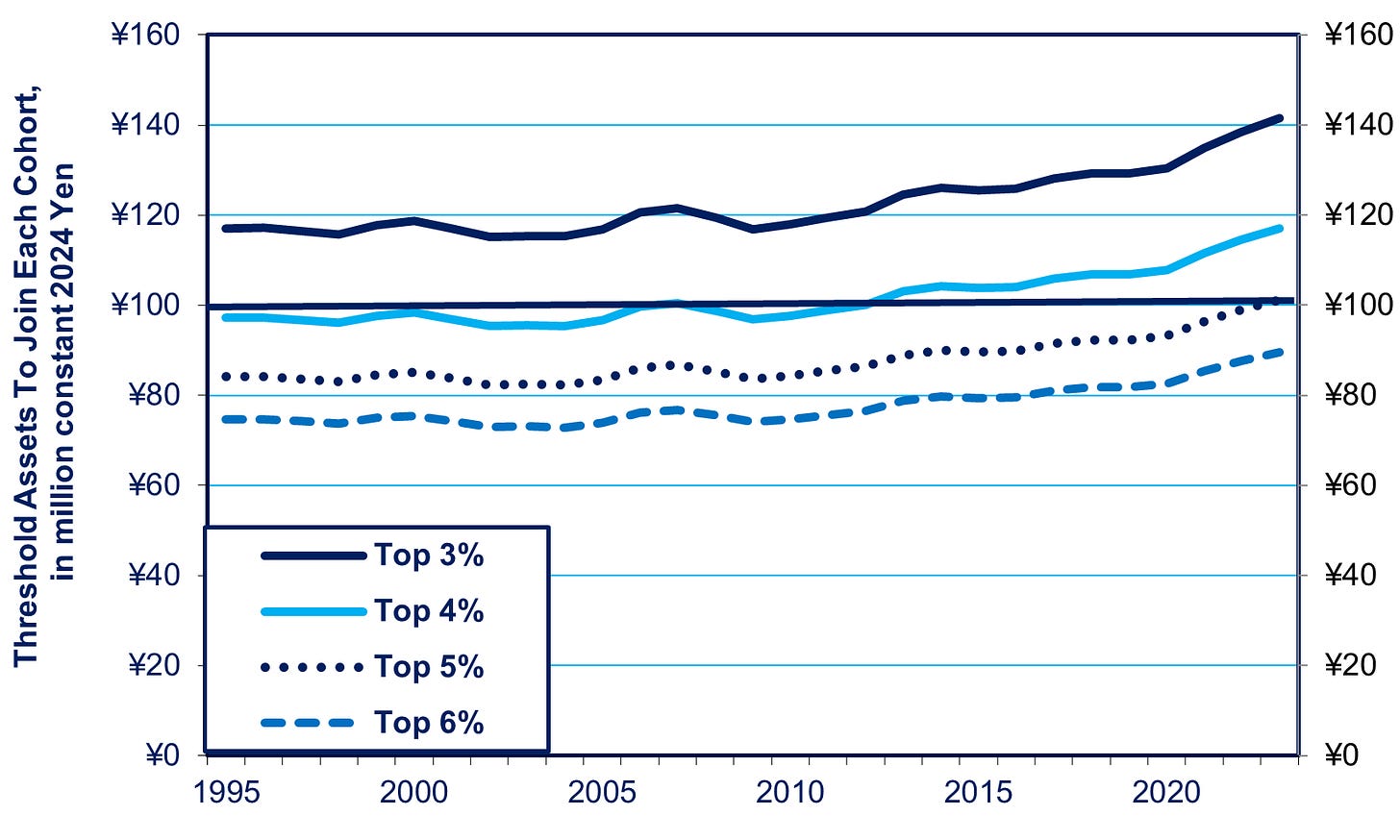

The recovery in property and stock prices over the last decade is increasing the number of millionaires, those with at least ¥100 million ($1 million PPP) in assets, including their primary home. In 1995 (the earliest comparable data available), the top 3% of adults (3.1 million adults) owned assets of ¥117 million in constant 2024 yen. It took until 2012 for the number of millionaires to expand to 4% (4.2 million adults) and remain stable. And in 2023, the millionaires club had reached 5% (5.2 million). If property and stock prices continue to rise at a healthy pace, 6% of Japan’s adults could become asset millionaires down the road (see chart below).

Why Should We Care?

Why should we care? The reason is that Goldilocks was right. When it comes to the number of millionaires (or billionaires) in a country, it should not be too few or too many, but “just right.” Countries with too few millionaires, especially self-made millionaires, often fail to provide sufficient incentives for individuals to start their own businesses or to become business executives or innovative technologists. Such an economy will grow more slowly and ultimately fail to provide a high enough standard of living for everyone. On the other hand, countries with too many millionaires or billionaires often have a skewed system that makes the richest even richer at the expense of everyone else. As the OECD has shown, that, too, can ultimately harm growth, not to mention contribute to the populist backlash. Talented but poor youth may be deprived of the best education, and the economy may be deprived of their talent. A working-class backlash may result in dysfunctional economic policies, something that’s been happening long before the rise of Donald Trump and his co-thinkers elsewhere, albeit in a much milder way. The OECD reports: "Between 1985 and 2005, for example, inequality increased by more than 2-Gini points [a common measure of inequality—rk] on average across 19 OECD countries....The average of cumulated growth rates across the same set of countries amounted to 28%....Had inequality not changed between 1985 and 2005 (and holding all other variables constant), the average OECD country would have grown by nearly 33%.” By contrast, in lands with the Goldilocks situation, a rising tide of millionaires and billionaires can potentially lift all boats, although it does not do so automatically.

If you want a higher living standard for the average person, it is necessary to give talented people the opportunity to become billionaires by, for example, creating companies that enrich the entire economy. In Japan, a third of the very rich—those with incomes above ¥100 million ($1 million PPP) per year—own their own business, some having created it and some having inherited it. Among Japan’s 11 newish billionaires in 2021, most had founded a company within the previous 25 years. One of them had created a web-based job matching service that enabled companies to find highly skilled employees and allowed the latter to move to new jobs where they could earn higher wages and take on more challenging work. For more on the new billionaires, see the “Introduction” to my book: The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future.

While having enough millionaires and billionaires can spur growth in per capita GDP, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the majority of the population will benefit. In neither Japan nor the US have they done so in recent decades, as noted in the real wage figures cited above. There is certainly no reason in any country why billionaires—no matter how beneficial the company they’ve founded—should pay a lower tax rate than their secretaries. I’ll discuss Japan’s “¥100 million income tax wall” in a later post in this series.

Does Japan Have Too Few Millionaires?

While the US exemplifies the defect of too many of the ultra-rich, Japan is commonly seen as exemplifying the “far too few” syndrome. But much of this is due to the impact of the lost decades.

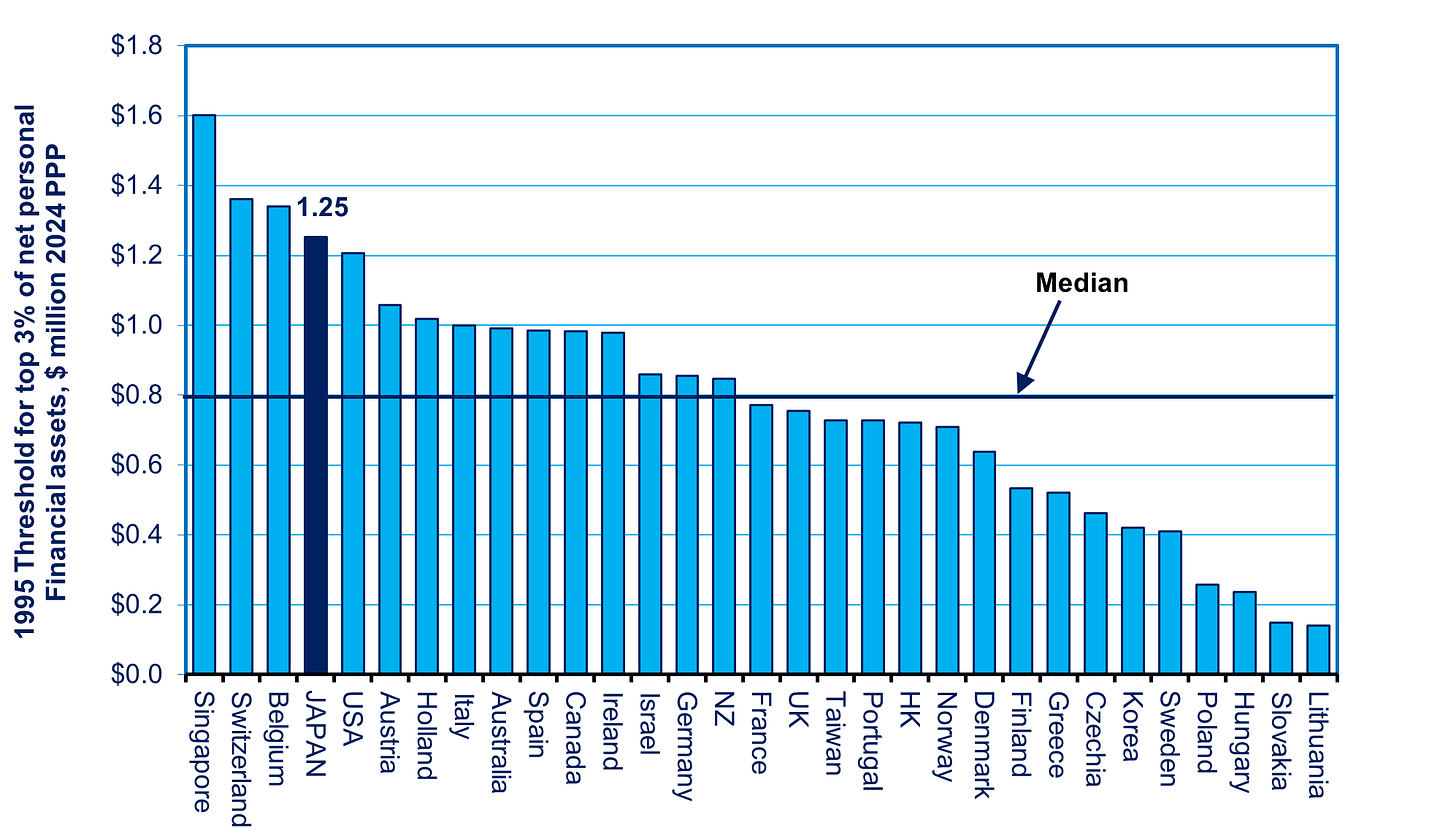

Yes, out of 31 wealthy countries in 2023, Japan ranked 22nd in terms of the threshold level of net personal financial assets needed to be among the top 3% of adults. This does not include one’s primary home, but it does include investments in real estate, along with savings deposits, stocks, etc. Japan’s threshold was $1.25 million. That’s 14% below the median threshold of $1.45 million exemplified by Hong Kong and Israel (see chart at the top).

Now, let’s see how different Japan’s situation was in 1995 (the earliest year for comparable data). Japan ranked fourth, with a threshold of $1.25 million, the same as in 2023. Back then, that $1.25 million put Japan’s threshold for millionaire status at a surprising 62% above the threshold in a typical rich country. So, Japan’s real problem is that, during the lost decades, wealth per adult in the top 3% stopped growing. Meanwhile, wealth continued growing in other countries. By standing still, Japan fell behind.

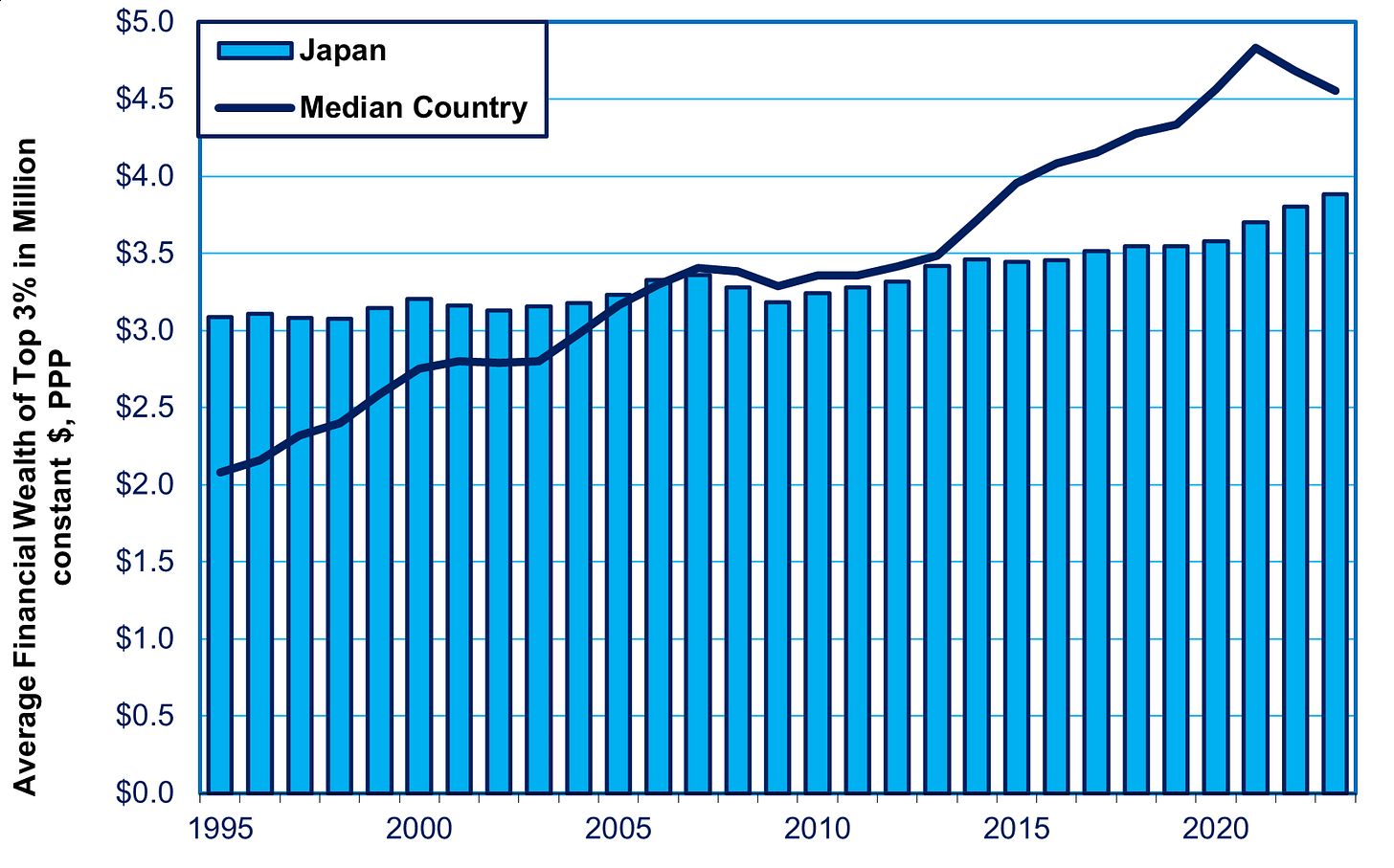

The top 3% of Japanese adults add up to around 3.1 million people (out of 104 million total) these days. While the charts above showed threshold numbers to join the 3% club, let’s look at what happened to the average financial wealth among all those in the top 3%, from millionaires to billionaires. During the three decades from 1995 to 2023, the average wealth grew just 26% in Japan but more than doubled in the typical rich country. So, back in 1995, the average among Japan’s richest 3% was 50% higher than in the median country. By 2023, it was 15% lower (see chart below).

Despite Japan’s relative decline, the wealth of most of Japan’s wealthy is not that far behind the median country. In Japan, it took $673,000 to enter the tribe of the top 10%, about 10 million adults. That’s 86% of the median country level. To enter the club of the top 0.01%, the 10,000 richest, it required assets equal to 95% of the median country level. On the other hand, to become one of the richest 0.001%, just 1,000 adults in Japan, it took $426 million. And that is just 66% of the median level, the only level at which Japan fell substantially behind (see chart below).

Note: The height of the bar and the percent number in the label show the ratio of Japan’s threshold relative to the median country at each level of income; the number in millions shows the threshold wealth needed to enter each level, e.g. $673,000 to enter the top 10%. All in 2023.

How About the Billionaires?

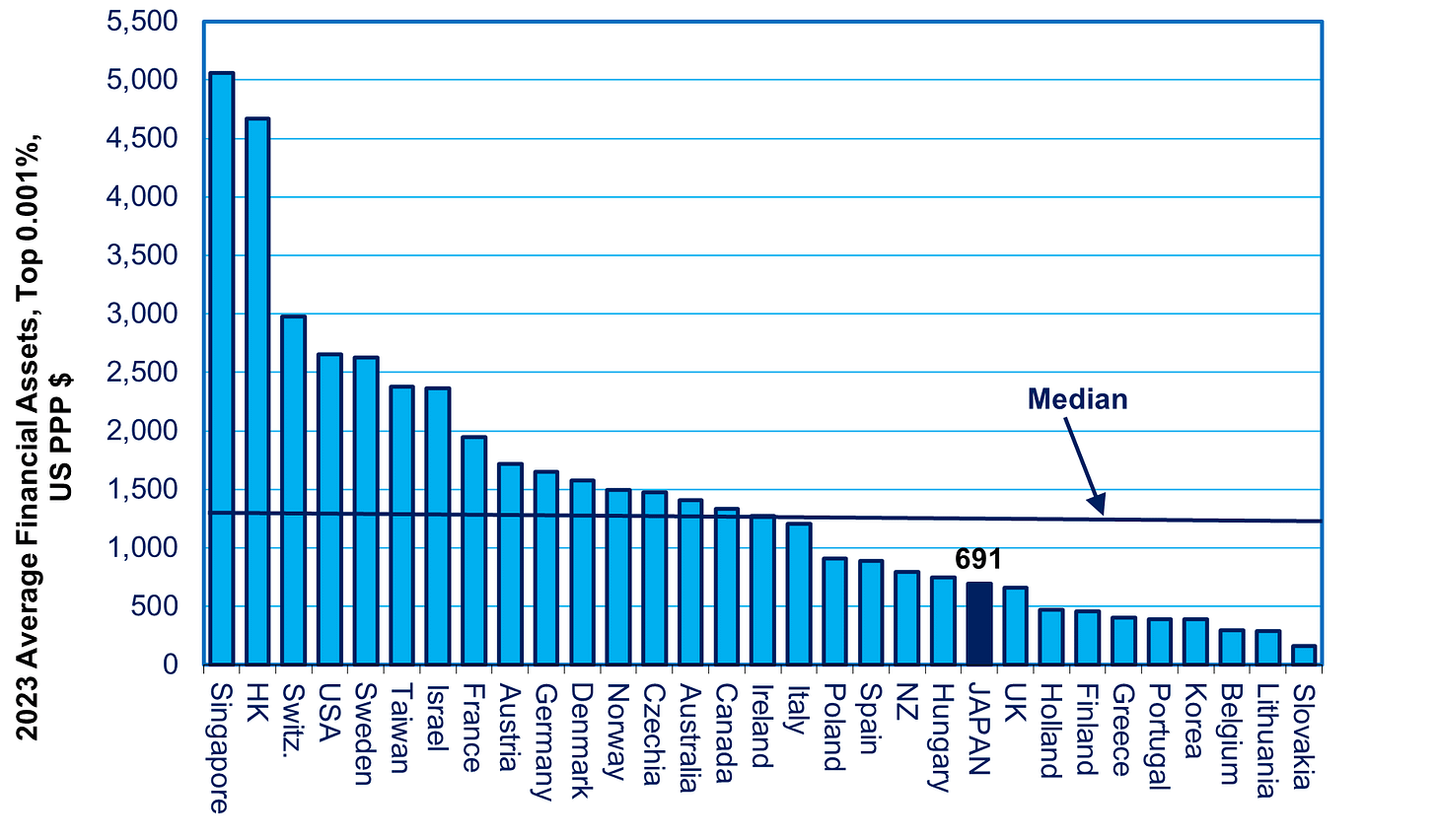

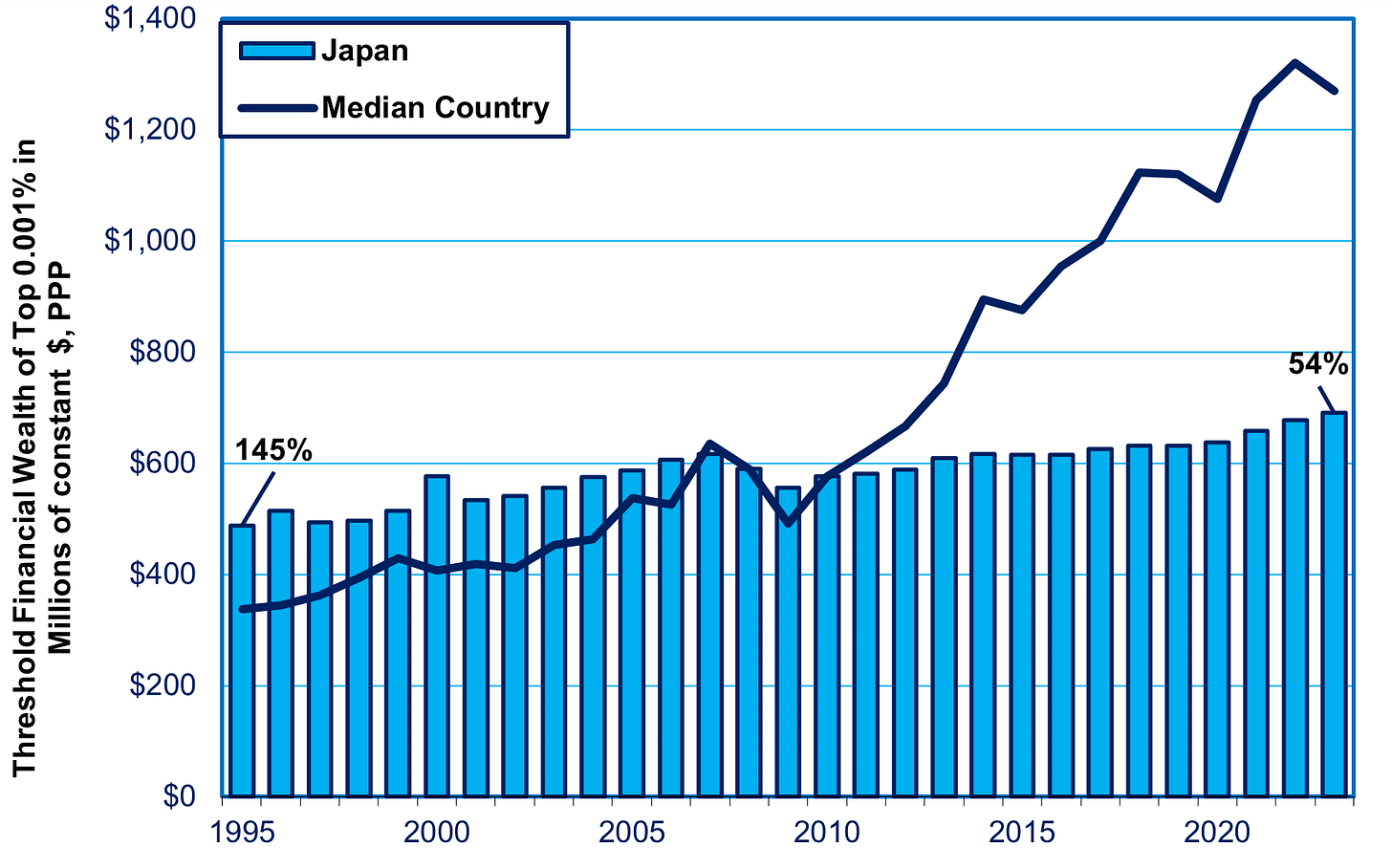

Where Japan does suffer a dearth is in generating billionaires. If we take the average financial wealth of Japan’s richest 1,000 adults—rather than the threshold level—it stands at $691 million, just 54% of the level in the median country (see chart below).

But it was not always so. Back in 1995, the average financial wealth of Japan’s richest 0.001% was 145% of the median level. Then, over the course of the lost decades, it fell behind as other countries grew (see chart below).

One note on the outlier numbers for billionaire wealth in Singapore and Hong Kong seen in the second-to-last chart. The populations of these economies are so small that, in 2023, this billionaire class amounted to around 50 people in Singapore and 70 in Hong Kong. These two cities’ role as financial and trading centers allows a few intermediaries to capture a great deal of the money flows. Hence, while some critics point to these two cities as points of comparison to Japan on the issue of personal wealth, they are so atypical that comparison is misleading.

Coming in Part 2: Why Japanese invest so little in the stock market. It’s not risk-aversion as much as a tax system that offers more rewards (including lower taxes) to those investing in real estate.

Corruption becomes an important factor in creating wealth in static/slow growth/slow de-growth economies. Who can safely engage in corruption is often determined through either political or crime connections, neither of which favor creative energy as much as a certain conservative rent extraction.

Interesting read. Unfortunately, it seems that Japan's government has zero interest in helping foreigners stay and establish profitable businesses, given their recent changes to the business manager visa fee, and they're encouraging or allowing the banks to freeze the assets of foreigners who have applied for a visa renewal while they're still waiting for the renewal. Sony Bank even said essentially "show us your new residence card before your old one expires" . Given that you can only apply no sooner than 3 months before the end date, as I understand it, but it is sometimes taking longer than 3 months for approval, this is physically impossible.