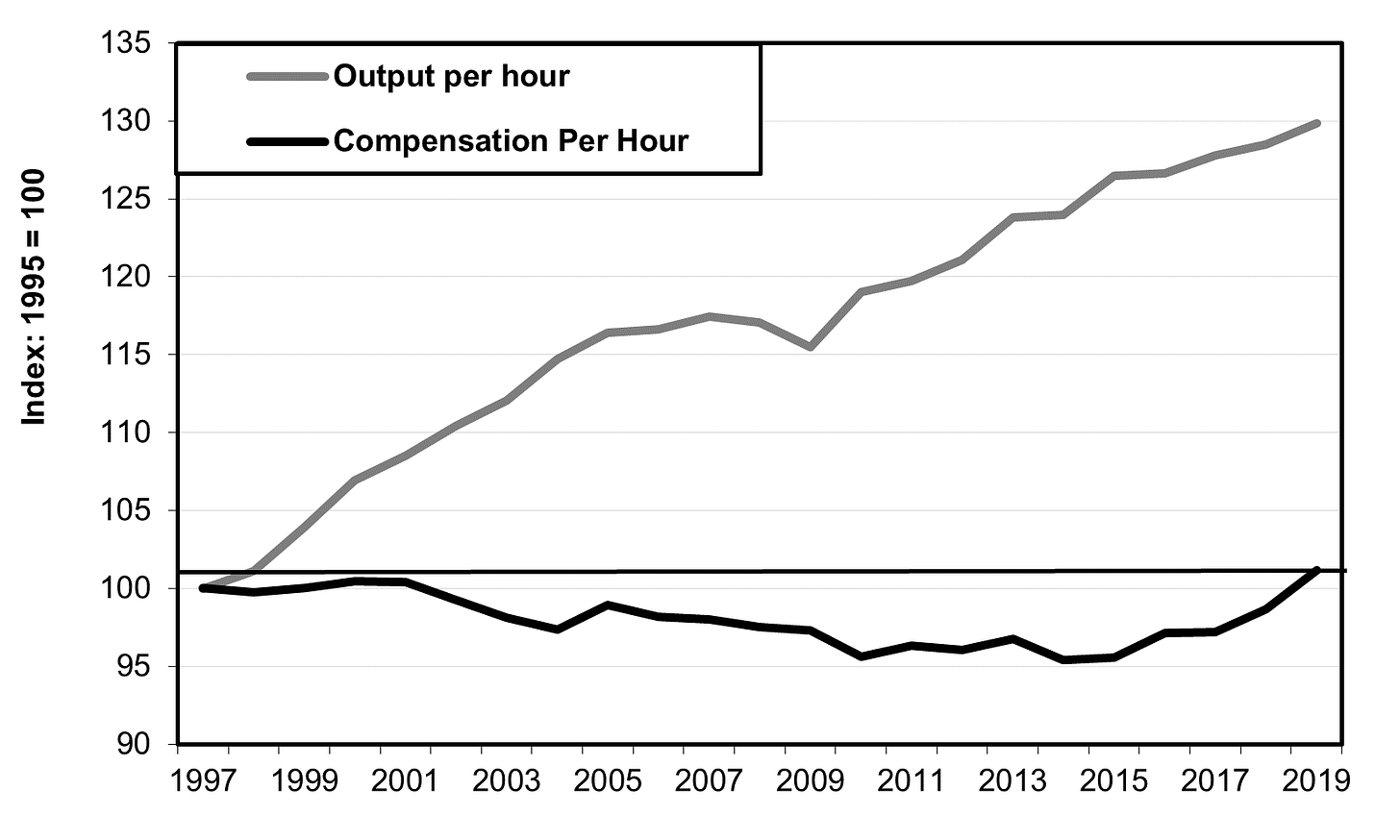

Japan is hardly the only rich country where real (i.e., price-adjusted) wages have been suppressed in the last few decades. But it’s the only one where wages have not just slowed, but actually fallen. Across the mature economies, wages have stopped doing what they had been doing for a century or more: growing at around the same rate as GDP. During 1995-2017, productivity, i.e., GDP per work-hour, grew 30% in 11 rich countries. However, real hourly compensation (wages plus benefits) grew only half as much: just 16%. While Japan’s productivity growth matched the others at 30%, worker earnings fell 1% (see chart at the top and the one for Japan data below). This performance is particularly shocking considering that, until recently, Japan’s workers got a higher share of national income than workers elsewhere.

Source: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDBI_I4

Unfortunately, the OECD does not provide comparable data for Korea going back to 1995, but during 2011-2021, while output work-hour rose 30%, real compensation per work-hour rose even faster: 45%.

This widespread slump in wage growth defies both history and economic theory. For decades, textbooks have told us that, in order for a market economy to be stable over the long term, consumer demand—and hence wages—have to grow around the same pace as output. Consequently, ever since the 1800s, the share of national income going to workers as opposed to owners of capital (in the form of profits, interest, rent, and dividends) has fluctuated around a fairly constant level. For some reason, things changed a few decades ago. “In advanced economies, labor income shares began trending down in the 1980s, reaching their lowest level of the past half-century,” the IMF reported in 2017.

One consequence is ever-rising budget deficits across the OECD. Since suppressed wages result in anemic consumer demand, most rich nations have had to make up for the shortfall in overall demand by spending a lot more than they receive in taxes.

The question is why. Some economists contend that the primary cause is technological, i.e., the rise of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), which they say has a different impact on labor than past technologies. Others put more emphasis on the weaker bargaining power of labor. While it’s likely to be some mixture in most rich countries, Japan’s result is so unusual that the political balance of power probably plays a larger role.

What is different about Japan? The biggest factor is the sharp upsurge of poorly paid non-regular workers. They rose from 15% of the labor force in the 1980s to nearly 40% these days. While regular workers, on average, earn ¥2,500 ($22) per hour, temporaries get just ¥1,660 ($14.70) and part-timers just ¥1,050 ($9.30).

But why did France, where non-regulars comprise a third of the labor force, suffer only a small wage-productivity growth gap during 1995-2011 (see chart again. A look at this underscores how politics makes a difference. In both, the law requires equal pay for equal work. France, however, enforces the law, including with use of labor inspectors. In Japan, by contrast, no Ministry is mandated to investigate the problem and prosecute violators. Victims have to launch and pay for their own lawsuits. Moreover, virtually all French workers—both regular and non-regular—are covered by union contracts, whether or not they belong to the union. In Japan, only union members are covered by the contracts and, by law, neither temporary workers nor those sent by dispatch agencies are allowed to join a union. To be sure, France’s non-standard workers face many difficulties, but outright pay discrimination is not one of them.

It was a Japanese economist, Hirofumi Uzawa, who in 1961 convinced economic orthodoxy that the long-term stability of the labor share of GDP was not just a strange coincidence, but a precondition for macroeconomic health. It is time for Japan’s policymakers to pay heed.

For the full article, see https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/476082 for English and https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/475188 for Japanese.

Agree 100% this is the single most important feature of Japanese politival economy over the past three decades. To the politics I’d just add the Keidanren’s role in perpetuating this cheap labour strategy

Because increasing NAIBU RYUHO...