Only a week after the yen reached the 20-year low of ¥125/$ and a majority of forecasters predicted it would weaken to ¥130 by the end of the year, the yen reached at ¥128.6 at the New York open today. It’s unclear how low and how fast the yen will continue to decline, though there will inevitably be days when the yen reverses course. Markets do not move in straight lines.

The specter of an out-of-control flight from the yen is setting off alarm bells in Tokyo, especially with an Upper House election just a few months away. Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki is no longer restricting himself to saying that the speed of the depreciation is too fast—the usual comment—but he’s now saying that the level is too low, which is unusual. “In a situation like now when companies have yet to sufficiently raise prices and wages, a weak yen isn't desirable. In fact, it's a bad yen decline.” Although Bank of Japan Haruhiko Kuroda keeps insisting that a weak yen is a “net positive” for Japan, even he is now saying that the speed of the fall is too “sharp.” Increasingly, economists in the private market are accentuating the negative impact. Even Keidanren chieftain Masakazu Tokura got into the fray, saying that, “In the past when the yen weakened, trade balance, current account and the economy were all good. It's no longer that simple.” A December survey of nearly 7,000 companies Tokyo Shoko Research found that almost 30% of companies said a weak yen was a negative for their business, while just 5% said it was a positive. Those that said the weak yen was negative on average cited a rate of ¥107/$ yen to the dollar as preferable.

Suzuki says he intends to consult with other Group of Seven countries and there have been talk in the press that the Ministry of Finance (MOF) might intervene in the currency markets for the first time in almost two decades, when it was trying to prevent the yen from strengthening. The reality, however, is that there is little that the MOF can do with lasting effect. Currency interventions do when gyrations have diverged greatly from fundamentals. And it may turn out the pace of yen weakening has gotten ahead of itself; if so, then joint intervention could break that momentum—at least for a while. However, the fact is that the current yen weakness does reflect fundamentals, and, in such cases, intervention does not work except perhaps to slow the pace.

Consider the last effort. From January 2003 to March 2004, the MOF spent a gargantuan ¥35 trillion ($320 billion at the 2003 ¥/$ rate), an amount equal to 1.7 times the entire current account surplus over that period. The MOF did so to prevent the yen from strengthening. Yet, at the end of the intervention, the yen was 9% higher than when the MOF started. All the MOF accomplished was to enrich currency speculators.

Watch The Interest Rate Gap

The fundamental economic factor behind the slide of the yen is that the fact the US and most other countries are raising interest rates rather sharply in order to fight inflation, but the BOJ insists that it will not raise rates in Japan. When investors can make more money by investing in American bonds, for example, rather than bonds in Japan, they shift money from Japan to the US. As they do so, the law of supply and demand sends the yen downward.

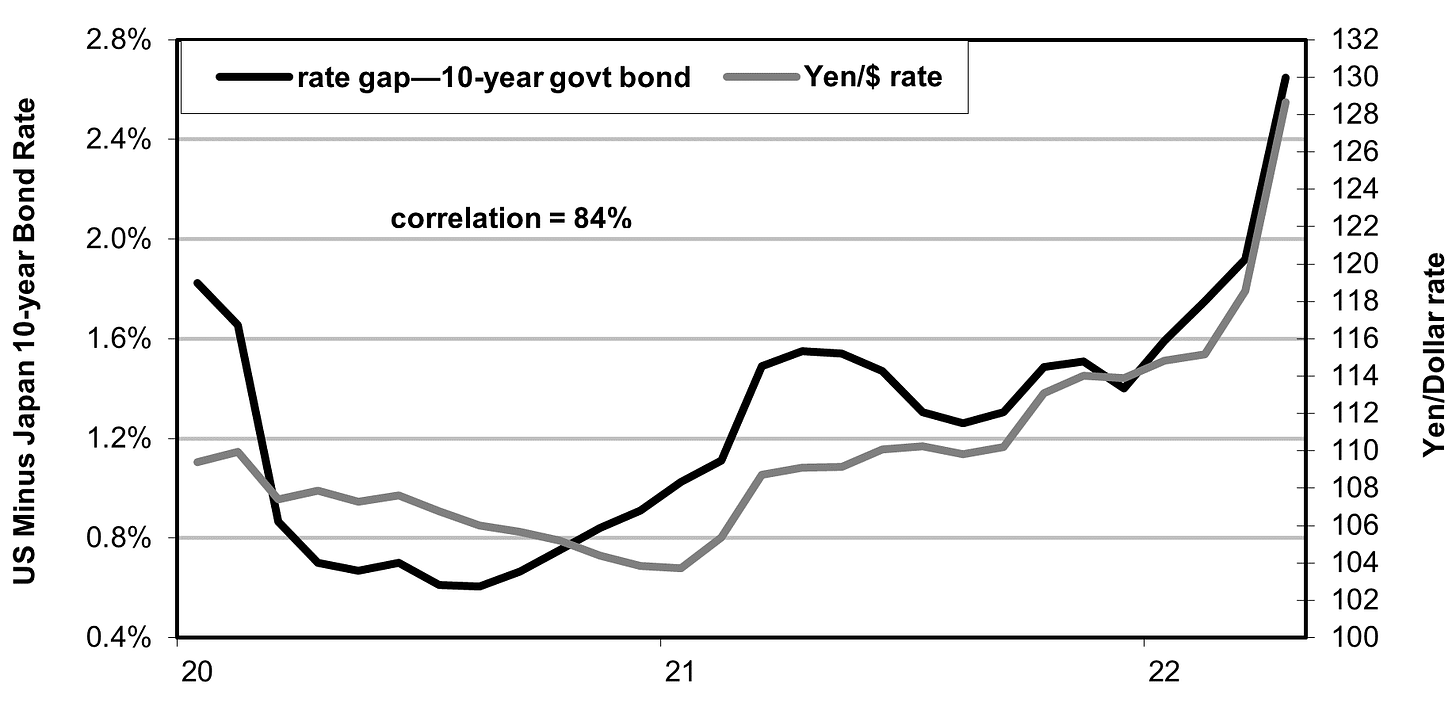

Back in September, when the interest rate on ten-year US Treasury bonds and Japan Government bonds was just 1.3%, the yen was worth ¥110/$. By February, when the interest rate gap widened to 1.75%, the yen weakened to ¥115/$. When the gap speedily widened to 2.65% as of April 19, the yen plunged to ¥128. In fact, since the beginning of 2020, there has been an extremely high 84% correlation between the ¥/$ rate and the size of the gap between ten-year US Treasury bonds and ten-year Japan Government Bonds (see figure at the top). Since the US Federal Reserve has said it will raise rates as many as six times this year, investors know the rate gap will get much wider.They are fleeing the yen in anticipation.

If Kuroda were to shift his stance on interest rates, that could have some impact, but he insists that he will not. On contrary, he has said that the BOJ will spend any amount of money required to keep the 10-year JGB rate no higher than 0.25%. It’s not just that he feels a weak yen is a good thing; it’s also because he does not want to raise rates until Japan hits 2% inflation on a sustained basis.

We will soon have a longer piece on this issue in Toyo Keizai, one that delves deeper into why a weak yen is bad for Japan, as well as how it reflects declining Japanese competitiveness.

Enlightening post once again, thank you!

I'm wondering why we haven't seen any significant acceleration in inflation in Japan yet? Both the weak yen and energy prices ought to have an impact. They certainly do already very visibly elsewhere (e.g. Europe, the US, emerging markets). But in Japan, inflation still seems to be very low. How come?

I'm aware of Japan's long deflationary (or low-flationary) history, companies‘ reluctance to raise prices, slow salary increases. But what I don't quite understand is how both the effects of high energy prices - and Japan is a major energy importer - and the weak yen can somehow just disappear in domestic prices.

Any explanation as to who has so far “taken on” this external price shock so that domestic price levels could stay so extraordinarily stable? And any sense on when this might change?

Richard; As you know, it is the BoJ not the MoF who can intervene in currency markets and Kuroda still isn’t showing any indication of doing so, choosing to stick with his “windmill” of inflation targeting. As long as the US-Japan rate spread continues to widen and Japan’s balance of payments are dipping to deficit (because of energy prices), the momentum is still strongly in favor of weak yen. One turning point may be a breakthrough in the Ukraine war, although a clear defeat of Russia may unleash its own can of worms.