Yen Going to ¥170/$?

If So, Is That A Change in Fundamentals or Speculative Over-Reach?

Source: Author forecast based on raw data from Wall Street Journal

Some notable experts see ¥170/$ on the horizon. Sumitomo Mitsui DS Asset Management’s lead portfolio manager recently stated that, while intervention could interrupt the process, “in the long term, the yen will continue to weaken toward 170.” Others, like Mizuho Bank, project ¥170 as a possibility, rather than a forecast. That doesn’t mean they are right. After all, at the beginning of the year, the consensus forecast was in the ¥130s. However, as of mid-June, a record-high share of trades was betting on the yen weakening even further.

It's Not Just The Interest Rate Gap

Up until December or so, the gap between American and Japanese long-term interest rates was an extremely accurate predictor of the ¥/$ level. As the gap widened, money was lured from Japan into the US. Investors have to sell yen to make that happen. Since December, however, the yen has steadily weakened even though the rate gap is no higher than it was back then (see chart below).

If the yen were still responding to the rate gap as it had been since January 2021, it would now be around ¥141 rather than ¥161—a huge 20-yen discrepancy (see chart at the top).

One possible explanation is a further shift in the fundamentals that changes the relationship between the rate gap and the yen’s value. If you look at the two trend lines in the chart below, you will see that, at any given rate gap, the yen these days is around 23 points weaker than it was at the same rate gap two decades ago. Perhaps another shift is beginning.

Intervention Fails Because No Speculative Frenzy

Even three bouts of massive currency intervention by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) have failed to stem the weakening trend for more than a short while—as was predicted.

The MOF claims that it is not targeting any particular level of the yen but only particularly rapid moves that reflect a speculative frenzy. Under international agreement, such frenzy is regarded as the only valid justification for intervention. The reality, as traders know, is that the MOF is targeting the level. That is one reason the US and other G7 countries have not cooperated with the intervention.

There has been no speculative frenzy, only a slow zigzag grind. On two-thirds of the days since January 2022, the yen has moved up or down by only 0.1%. Two of the three big interventions took place when the movement was at that 0.1% range, and only when the yen was getting too weak (see chart below).

Note: The chart shows the percent change in the yen’s value on each trading day using a 30-day moving average.

Theory One: A Change In the Fundamentals

If the interest rate gap is not pushing the yen to 170, what additional forces are creating the ongoing weakening?

One theory is that the market perceives a big change in the economic fundamentals that have decreased demand for the yen. Like all other prices, the yen/$ rate is determined by supply and demand. When Japan runs a big trade surplus, that creates a demand for the yen to pay for Japan’s surplus of exports. Conversely, if Japanese investors prefer to invest overseas because they can earn more, they need to sell yen for foreign currencies. That’s one reason the interest rate gap has been such a good predictor for most of the past four years.

The best measure of how much fundamentals have weakened the yen is the “real effective exchange rate” vis-à-vis all of Japan’s trading partners. The real yen reflects both Japan’s competitiveness in global markets and its domestic strength. As seen in the chart below, when Japan was gaining competitiveness during the 1970s and 80s, the real yen rose. As the “lost decades” set in, the real yen dropped. It is now weaker than at any time on record going back to a half-century ago. One reason is that Japan, once the target of trade hawks for its chronic trade surpluses, has run a trade deficit in goods and services in eight of the 13 years since 2011.

Source: Bank of Japan

One thing is worth noting: the decline of both the nominal and real yen vis-à-vis all of Japan’s trading partners seems like a continuation of the steady drop in the last five years. Perhaps this year’s ratchet vis-à-vis the dollar may be exceptional.

The Biggest Changes In Fundamentals

An increasing number of economists are focusing on the structural factors in Japan’s weakening yen in addition to the interest rate gap. Among them is Mizuho Bank’s Chief Market Economist, Daisuke Karakama, who has given the Ministry of Finance (MOF) briefings on this explanation. Here are a few of these changing fundamentals:

NISA accounts: The most abrupt of all the changes is a set of new rules on Japan’s NISA accounts—a tax break on investments in the stock market. These took effect in January this year. Investors rushed into these accounts (not necessarily new money; much may come from households switching their stock holdings from those not tax-advantaged). A large proportion of these NISA accounts were used to invest overseas. Barclays Securities recently estimated that an enormous ¥12 trillion ($74 billion) in NISA money could be sent overseas this year. If true, that would offset half of the entire current account surplus. The latter surplus—the trade surplus in goods and services plus income from overseas investments—is the main source of net demand for yen. A new development erasing half of that demand could explain much of this year’s ratchet. It seems that “Mrs. Watanabe”—the proverbial housewife investor—has more confidence in overseas stocks than do the financiers trying to get them to buy Japanese stocks.

Mounting Digital Deficit: Japan has never been very competitive in services. But the backwardness of its companies in digital technology is wreaking havoc on the yen. What Japan has earned in service exports is increasingly offset by huge payments for software as well as enormous fee payments to six US behemoths—Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Microsoft, and Google—as well as other firms in other countries for cloud storage and applications, other apps, consulting services, online ads, music, etc. Not even the recent boom in tourism has been enough to overcome the digital payout, and the latter seems likely to grow. A 2023 Bank of Japan report noted this trend.

Companies keeping overseas profits overseas: One of the biggest items in the current account surplus is the profits that Japanese companies make via their overseas affiliates, i.e. profits on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Indeed, as the yen weakens, those profits loom even larger when they are converted to yen. As a result in fiscal 2023, profits on FDI equaled 80% of the entire current account surplus (and a big portion of the profits of multinationals, one of the reasons stock prices are up).

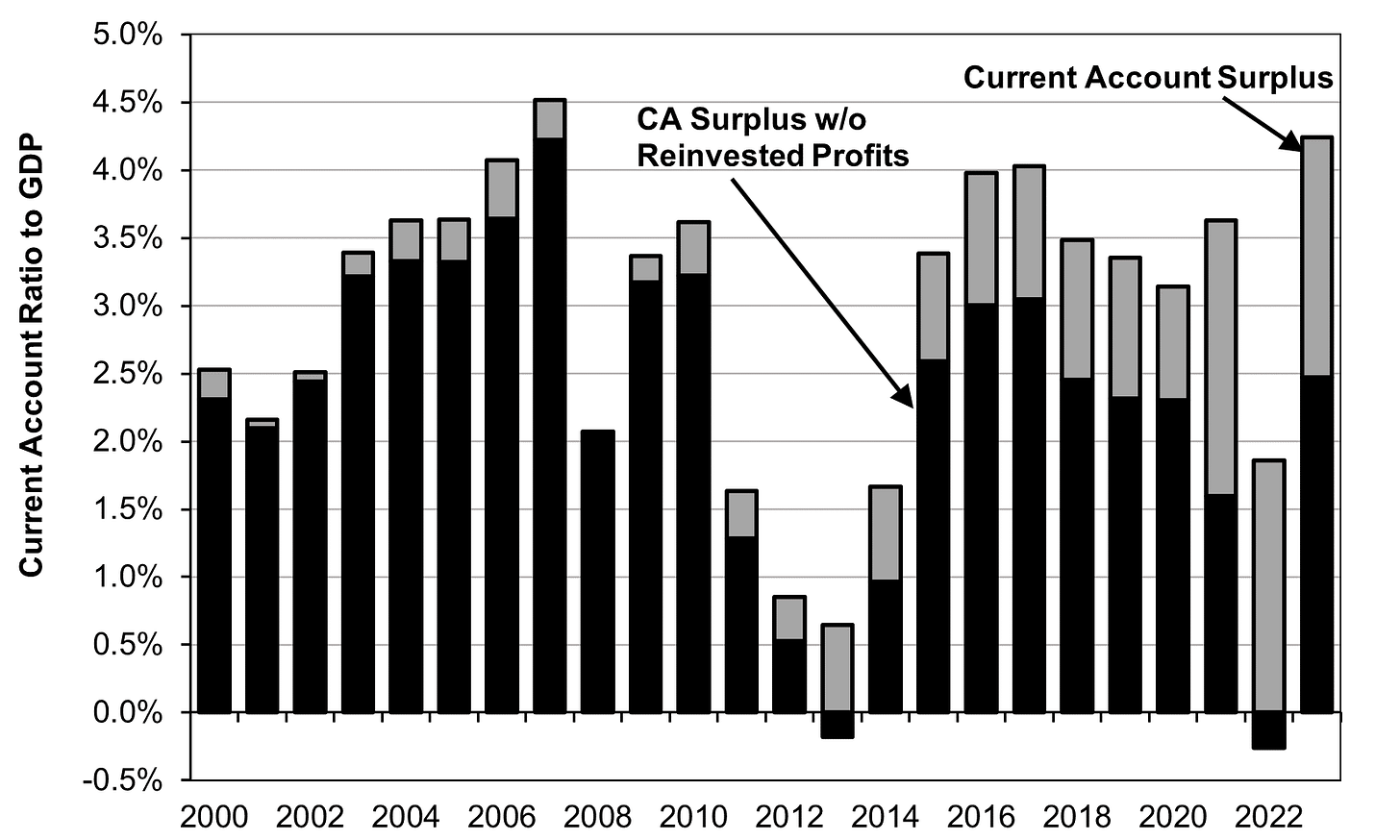

The problem for the yen is that companies are leaving more and more of those profits overseas rather than bringing them back home, perhaps because they expect the yen to continue weakening. Bringing the profits home requires converting other currencies to yen; leaving them overseas lessens demand for the yen. In the official tables, this is labeled “reinvestment,” even if the owner has the affiliate park the money in some financial asset. In the past, the impact of such reinvestment was negligible. But it has steadily increased over time. In fiscal 2023 (through March 2024), the total current account surplus equaled a substantial 4.2% of GDP. However, if we deduct reinvested profits—the actual money coming back to Japan, thereby creating demand for the yen—the current account in cash flow terms was only 2.5% of GDP (compare the height of the grey part of the column in the early 2000s to more recent years in the chart below). Karakama has stressed this facet of the picture.

Source: https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/reference/balance_of_payments/ebpnet.htm Note: The entire bar is the size of the CA surplus; the black part is what remains of the CA surplus after reinvested profits are deducted; the grey part is the difference.

Theory Two: Momentum Investing

Every day, more than $2 trillion changes hands as currency traders buy and sell yen in the same commodities markets where others trade in copper, pork bellies, and interest rate swaps. This activity dwarfs all the transactions for trade in goods and services, in FDI, and purchases of stocks and bonds. And virtually none of these currency trades have any relationship to the latter. These traders do not take possession of actual yen, no more than they take home the pork bellies that they buy. They don’t buy “stuff,” they buy contracts that exist only as bytes in the cloud.

Nonetheless, to a large extent, these transactions dictate the price of the yen that governs what Japanese buyers of oil have to pay and what sellers of cars get in sales revenue. A gigantic tail is wagging a tiny dog. To make it worse, traders do not bet based on their perception of economic fundamentals; those who try to do so end up losing their shirt. Rather, they obey the mantra “the trend is your friend”—even if the relationship sours after 45 seconds. When the trend changes, they can turn their back on previous positions on a dime. This leads to momentum investing. They buy something because its price has been going up and that decision makes it go up even more. Until it no longer does. And then it falls. This is normal. But when it goes to extremes, momentum investing can create bubbles and busts, whether in stocks, or bitcoin, or Japanese real estate in the 1980s.

Eventually, fundamentals do cause markets to correct and come back down (or up) to earth. But “eventually” can sometimes take quite a while. As Keynes famously said, “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

Undoubtedly, momentum investment is part of the story of how the yen got to ¥161 and may (or may not) go to ¥170 at some point. But it cannot be the whole story. If it were, daily movements in the yen would be far larger than just 0.1% of the yen’s value (as shown in an earlier chart). Moreover, the MOF’s massive intervention would have had a far greater impact.

Fasten your seat belt; it could be a bumpy ride.

On some days on amazon.co.jp

Negative divergences abound here And old resistance exactly here from April 1990

wild times. Time to buy a house n Japan?