From Fetish To Fetter: China's Model Of Investment-Led Growth

China’s Growth Prospects, Part II

Source: Calculations based on data from https://dataverse.nl/api/access/datafile/354095

At a recent secret meeting, a group of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elders told Xi Jinping it was time to fix the country’s economic turbulence, warning that it risked social turmoil that could weaken CCP rule. Xi dismissed their criticisms, and later angrily told associates that today’s problems were the fault of his predecessors beginning with Deng Xiaoping himself. He claimed he had spent a decade trying to clean up their mess. Xi has a personal problem with Deng claiming the latter did not give Xi’s father enough credit for the launching of economic reform. Xi’s rant left aides, including his own Prime Minister, shaken. It’s telling that someone decided to reveal the reprimand of Xi to a reporter at Japan’s Nikkei newspaper.

The incident helps explain why China finds it so hard to make the needed course correction in economic strategy. Beyond Beijing’s unwillingness to let go of once-wonderful practices that are now obsolete—including its investment-led growth model—there are matters of ideology, politics, nationalism, personal resentments, and power-seeking.

More Investment Vs. Smarter Investment

Too much of a good thing is no good. Yes, in lifting a country out of poverty, huge amounts of investment are indispensable. Infrastructure, factories, equipment, stores, etc. let one farmer, factory worker, or service staffer do the work that once took many. Eventually, however, investment-led growth reaches diminishing returns, and, as some of Xi’s predecessors recognized, the baton needs to be passed to consumer spending. These predecessors called this needed shift “rebalancing,” while Xi rejects it as “welfarism.” Investment, much of it increasingly unproductive, remains outrageously high relative to GDP, while consumer income and spending are deliberately kept extraordinarily low. The result is an economy whose biggest growth sector is unpayable debt.

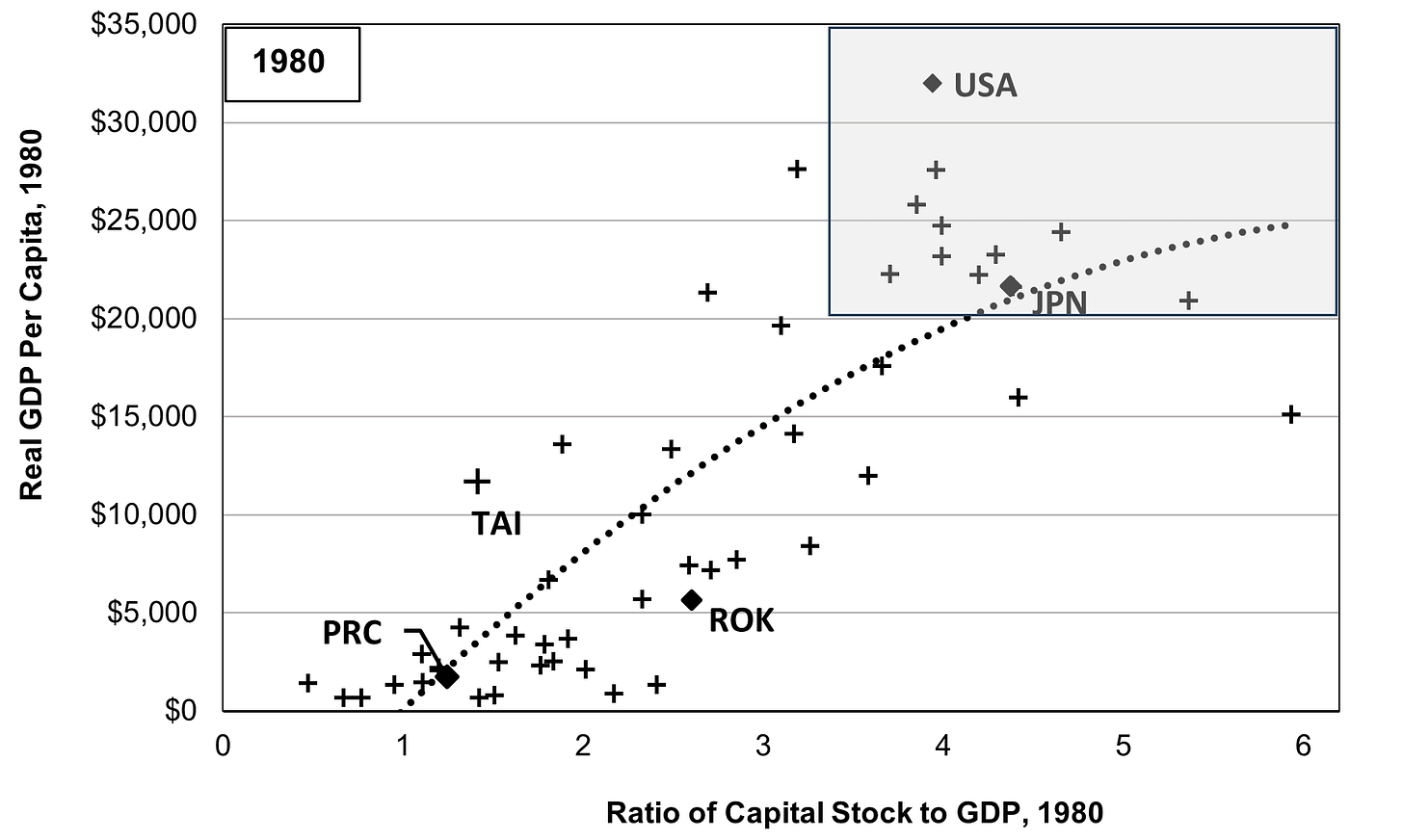

As seen in the chart below, rich countries have a much higher ratio of capital stock to GDP than poor ones. However, once a country becomes rich enough—$20,000 per capita GDP in the shaded corner of the chart —becoming even more capital-intensive does not necessarily lead to higher living standards.

In a rich country, or even an upper middle-income one like China, what most determines further progress is not more tools, but smarter ones. A 2023 PC can do things impossible for a 1990 PC. Equally important is how well companies use the capital. Japan’s per capita GDP is far less the America’s even though it is more capital-intensive, partly because Japan’s companies get too little benefit from their investments in digital technology.

China, too, fails to get the most from its immense investments. One factor is state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which accounted for about 40% of China’s GDP as of 2019. Compared to China’s private companies, the SOEs get about only half as much output for every yuan (the Chinese currency) they invest, according to one estimate. In the 1990s, Beijing greatly reduced the role of SOEs, but they’ve rebounded under Xi (details in the next posting). Worse yet, to prop up economic demand in the face of weak consumer income, China keeps pouring money into infrastructure whether or not it is still needed. Infrastructure investment alone now averages a very high 16% of GDP. While much is marvelous, like the cell phone towers one sees all over rural mountaintops, an increasing share resembles Japan’s famous “bridges to nowhere,” e.g., some local airports. The same goes for all the money poured into new housing, much of it financed with debt, still vacant, and bought by citizens hoping to gain from a price hike—as in Japan’s 1980s property bubble.

Here’s the upshot. Back in 1995, China could increase its GDP by 1% if it hiked its stock of capital by 2%. Now, to get the same 1% expansion of GDP, it has to hike its capital stock by 6%. Consequently, just to maintain the same rate of GDP growth, it has to devote ever-larger shares of annual GDP to investment. That, as I’ll detail below, is unsustainable and is a big factor in why China is in such trouble today.

How China Compares to Other Countries

Let’s see how China compares to others over the past four decades. The short answer is not well (see chart below).

Notice first that the 2019 trend line is higher than the 1980 trend line. This is largely because better technology and more efficient companies enable countries to get far more “bang for the buck” from their investments. American per capita GDP is double what it was in 1980 even though American capital intensity is somewhat less than in 1980. Notice in the corner of the chart that, in 2019, once a country reached $40,000 per capita GDP, further capital intensity did not yield greater wealth. Compare the US and Taiwan to Japan and Korea.

China multiplied its per capita GDP eightfold in just four decades largely because it raised the ratio of capital stock to GDP rose from just 1.2 in 1980 to 5 in 2019. While the result is spectacular, the chart above shows that China did not get as much benefit as it could have. In 2019, its level of per capita GDP ($14,000) was far below the 2019 trend line. So many countries that had invested less got more growth per dollar of investment.

To compare countries, we need to ask: How much of an increase in GDP during 1980-2019 did a country get for each 1% hike in its capital stock? The USA got a 1.3%, followed by Germany at 0.9%. Among the Asian growth stars, China came in last at just 0.2% (see chart at the top of this blog).

With better policies, China’s miracle might have been even more miraculous. Some of Xi’s predecessors recognized this, e.g., Prime Minister Zhu Rongji’s reduction of SOE prominence in the 1990s (details in next installment).

The Irony: Excess Investment Ultimately Leads to Weak Demand

Why do we care about all of this? Because a country that has to invest a larger share of GDP to achieve X% growth has less GDP left over for household income and consumption. Because the productivity of China’s capital is so low, in 2019, China had to spend 45% of its GDP on investment, far more than any other among 64 countries. It allotted just 40% to consumption, less than all the rest (see two charts below).

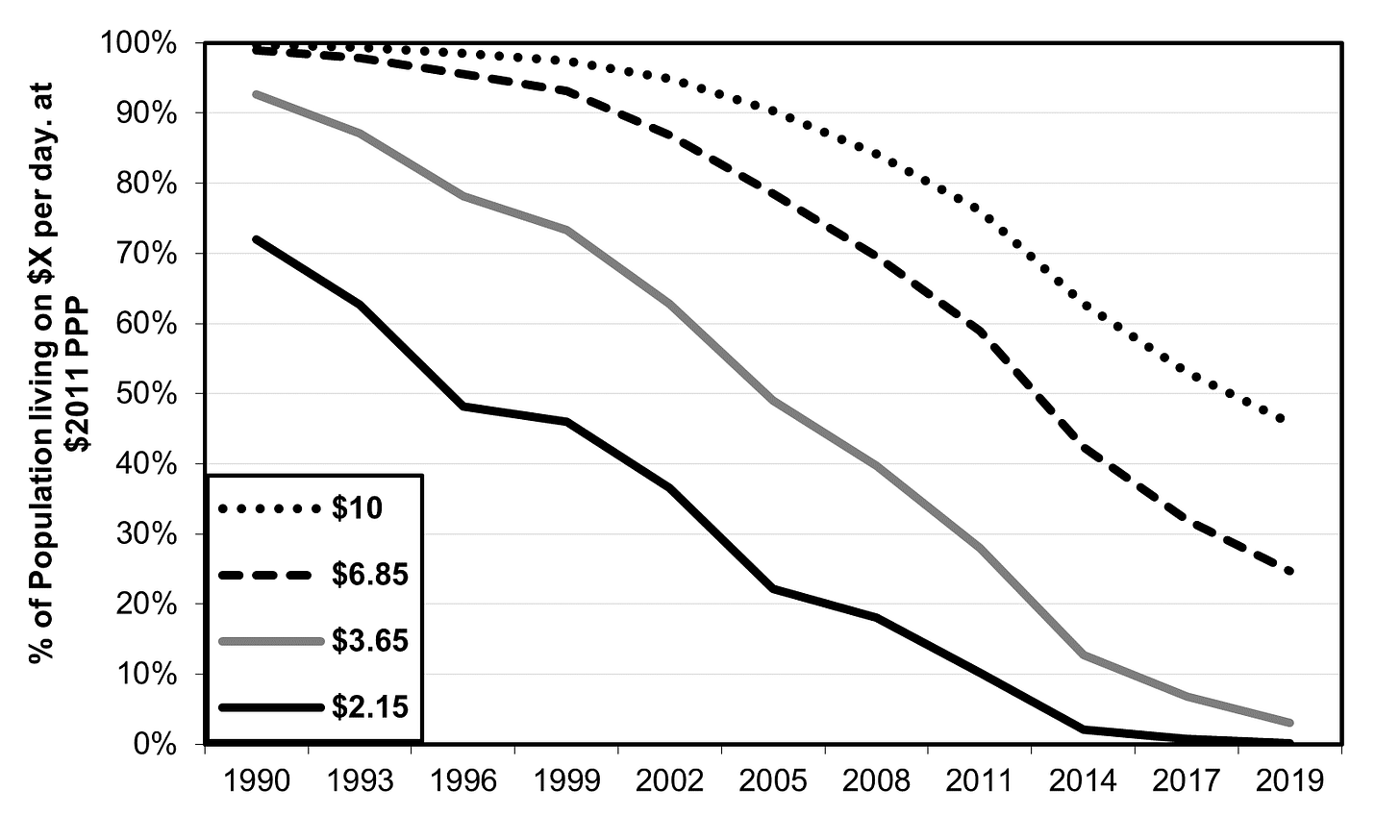

This has consequences for both living standards and macroeconomic stability. In a feat that has inspired the world, China’s economic miracle has lifted 1.4 billion people out of abject poverty. When Deng ascended to power in 1978, almost all Chinese eked out an existence at less than $2.15 or $3.65 ($2017 PPP) per day. Now, just four decades later, almost no one is that poor (chart below).

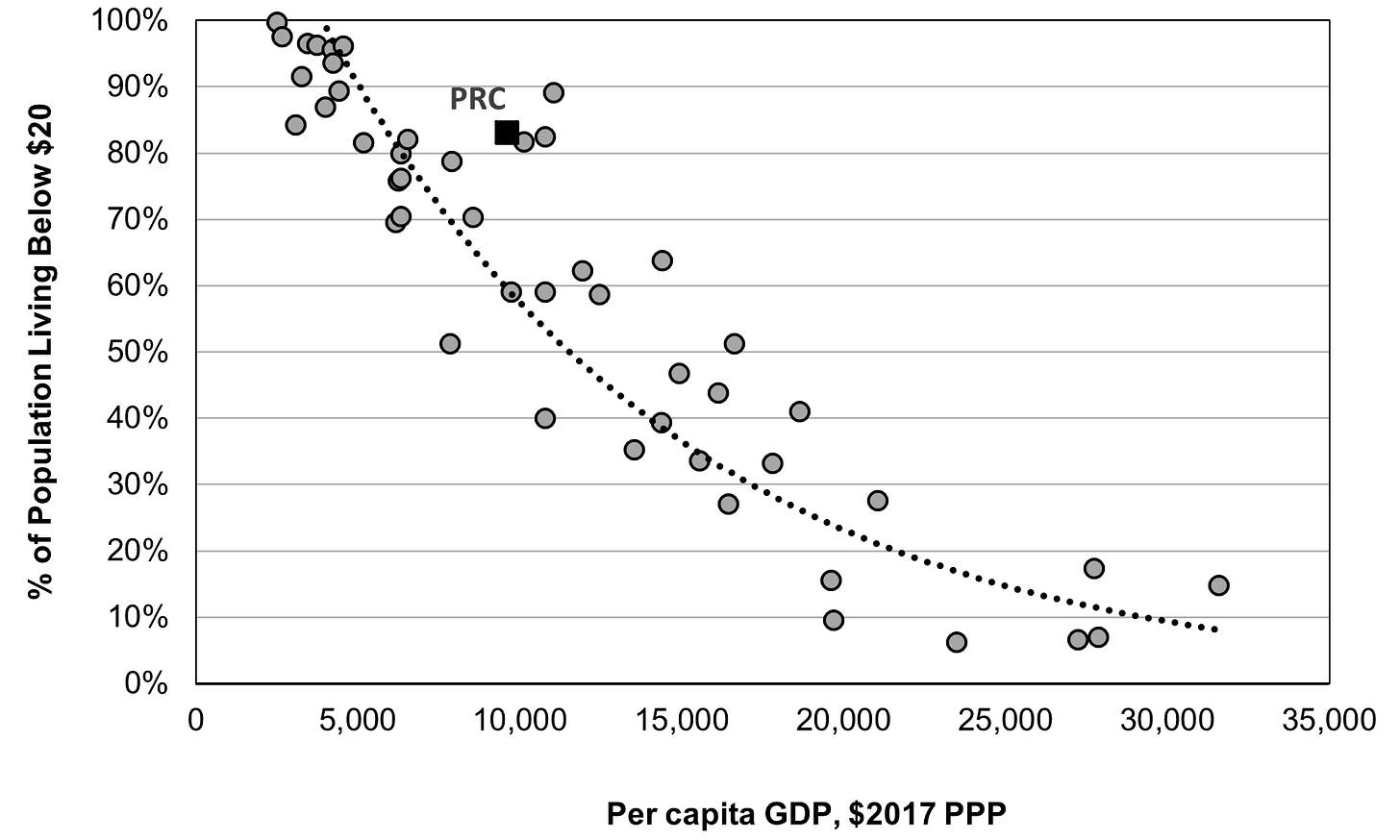

Source: https://pip.worldbank.org/home

However, compared to other countries at its per capita GDP, China has lifted fewer of its people above a standard that counts as poverty in upper-income countries: $20 per day. Just 20% of all Chinese (and just 6% of rural Chinese) do so. By contrast, a typical country at China’s per capita GDP has lifted twice as many, 40%, above that measure of poverty. Rich countries have lifted 95% (see trendline in chart below). Few Chinese live like those seen in Beijing, Shanghai, or other first-tier cities.

Note: For a better visual of China’s position, countries richer than Italy are not included in this chart

Why aren’t China’s people benefiting more from its growth? In the service of investment-led growth, household after-tax income has been suppressed: from 67% of GDP in 1992 to 55% in 2022. As in Japan in the 1950s-60s, interest rates on savings have been kept very low so as to provide cheap investment funds to companies. A third of Chinese are being forcibly kept in rural areas, where median incomes are 60% below urban incomes. An estimated quarter of a billion Chinese have illegally migrated to the cities because even meager incomes there are better than those in the “boondocks.”

Then, to induce households to save a huge share of their income (35% in 2019), rather than spend it, the government kept the social safety net low. Most people cannot get health insurance and know to show up at the hospital with a wad of cash. Pensions were actually reduced so people would have to save more for their old age.

The Macroeconomic Need For Rebalancing

Xi may care less about people (as long as they are quiescent) than he does about building an economic foundation for a strong state. However, the CCP needs to consider how this obsolete model is now undermining the economy on which the Party is counting. For one thing, there’s a limit to how far investment can rise as a share of GDP. Beijing can force SOEs to invest but not private firms, one reason that Xi is increasing the role of SOEs. Like a bicycle that will tip over if it stops moving forward, China’s GDP growth decelerates if the investment share of GDP merely stops growing. As the chart below shows, this is already happening. That would not be happening if it could improve the productivity of its capital.

Note: Penn World data on capital stock ends in 2019 while IMF data on GDP are forecast through 2028 at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April/download-entire-database

How, then, does Beijing prop up aggregate demand, if it has suppressed consumer purchasing power? It has even more need to prop up inefficient investment: airports for no one or housing that stays vacant. And so, in a vicious cycle, excess investment lowers personal consumption, requiring still more investment to keep the economy afloat. This process multiplies the debt load of government entities, SOEs, private companies, and households. That is what is now producing fears of some sort of Japan-like financial dislocation.

Prime Minister Wen Jiabao Vs. Xi Jinping

It’s not as if elites in China are unaware that the economy needs rebalancing between investment and consumption, just as Japan’s famous Maekawa Commission stressed the need for rebalance just a few years before Japan’s 1980s bubble popped. Whereas Japan’s elite dismissed the Commission’s warning, Beijing claimed to have read the writing on the wall. In 2004, Prime Minister Wen Jiabao (who served under CCP leader Jiang Zemin) called for a shift to consumption-led growth. And, in a 2007 press conference, he called China’s path “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.” Unfortunately, he would not, or could not, do what rebalancing would have been required. Household income continued to decline relative to GDP, and so consumption stayed weak while the investment share rose even higher (chart below).

Not surprisingly the current economic turmoil has revived calls for rebalancing. Xi, nonetheless, seems downright hostile. Wen had promised, but failed to deliver, widespread health insurance, but President Xi reportedly opposes it. In a 2016 speech, Xi insisted that, “Our country does not have insufficient demand,” and in 2022, Xi “warned about the risks if Beijing does too much to prop up households to promote consumption.” He specifically warned against “excessive guarantees” (like widespread health insurance and unemployment compensation) that smacked of “welfarism.” While, under the slogan “common prosperity,” Xi has talked of reducing the severe inequality among households over the next quarter century, he resolutely opposes ending the increasingly futile attempt at maintaining investment-led growth.

Processes that are unsustainable will sooner or later fall, as is already happening in China (see again the chart above). If the fetish of investment-led growth is not corrected in an orderly way, it’s more likely to “resolve” itself in an unorderly fashion. To paraphrase Casablanca, not to mention the CCP elders in their secret meeting with Xi: if you don’t fix this problem, you'll regret it. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow. But inevitably.

Sadly, China is great in good part because its citizens are economically beaten down. Mr. Roberts, I think you're physically unable to utter any criticism of the CCP.

True, but it's still fascinating to know that they did this much. Your piece does fortify the case that Adam Posen wrote recently -- he's another one that I do read whenever I have the chance.