China On Track To Pass Japan in Auto Exports

EVs Help China Do To Japan What Japan Did To The US In The 1970s

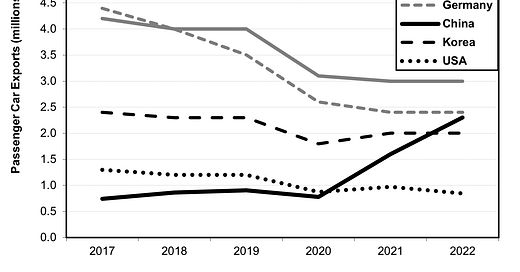

Note: Passenger cars only, no light trucks like SUVs or pick-ups; much of the decline in overall exports in 2020-22 reflects the shortage of computer chips triggered by Covid

Three recent bits of news made me wonder whether Toyota and its fellow Japanese automakers are risking a repeat of the decline of the Detroit Three, all because of their resistance to electric vehicles (EVs).

The first item was the news that 40% of Americans who bought Teslas had switched from Japanese brands, primarily the Toyota group and Honda (see chart below). Even though so many Teslas are priced like luxury cars, the biggest losers include models aimed at the middle-class market. The top five Model Y conquests are the Lexus RX, Honda CR-V, Toyota RAV4, Honda Odyssey, and Honda Accord. Meanwhile, the top five Model 3 conquests are the Honda Civic, Honda Accord, Toyota Camry, Toyota RAV4, and Honda CR-V. Imagine the difference if Toyota and Honda had been offering EVs. Once brand loyalty is lost, regaining it is not so easy.

Note: Brands from which Tesla buyers switched; Toyota group includes Toyota, Lexus, and Subaru

Source: S&P Mobility at https://www.spglobal.com/mobility/en/research-analysis/new-ev-entries-nibbling-away-at-tesla-ev-share.html

Secondly, at a time when 25% of new car sales in China consist of EVs and plug-in hybrids, Japanese brands are losing sales in that country due to their lack of EV offerings. China’s sluggish economy meant that total auto sales fell in the first three months of this year, but Japanese brands tumbled the most, a serious 32% year-on-year sales decline. This compares to just 9% for American and European brands, and 7% for Korean makes. Losing share in the world’s biggest market with the fastest growth does not bode well.

The final item, the most shocking of all, is that, in 2022, China surpassed Germany to become the world’s second-largest auto exporter, and it is on track to surpass Japan in the next few years. (The chart at the top includes only passenger cars where China did not quite surpass Germany; counting cars plus light trucks, China exported 3.1 million autos compared to 2.6 for Germany and 4.36 for Japan).

This, too, is largely because of EVs, which accounted for half of all Chinese auto exports in the last few months of 2022. True, many of these auto exports are made by foreign brands like Tesla and GM’s joint venture with state-owned SAIC producing vehicles on Chinese soil, mostly in joint ventures with Chinese companies. Increasingly, however, the EV exports come from Chinese companies like BYD that have no joint ventures with foreign companies and which export EVs to richer countries at prices aimed at the middle class (around $30,000 or so). As a result, China’s exports no longer focus simply on developing countries. In the first half of 2022, Western Europe accounted for around 34% of China’s total passenger car exports. Fitch Solutions predicts that China’s share of the European EV market will rise from 5% in 2022 to 15% as early as 2025. So, Japanese brands are losing sales to their Chinese counterparts in global markets as well as in China.

Repeating Detroit’s Sad History

The irony is that Chinese brands seem to be doing to Japanese automakers exactly what the latter did to the Detroit Three. Moreover, it is doing it for the same reason: a shift in technology and market conditions that dominant oligopolists dismiss and fail to adapt to. In the case of autos, the trigger for Detroit’s decline was skyrocketing oil prices and thus growth in demand for smaller cars. Today, it’s EVs.

Until the two oil price shocks of 1973-74 and 1979-80, the Detroit Three’s oligopoly seemed unassailable. Throughout the 1960s-early 1970s, its market share in America held up at a stunning 85%. When oil prices suddenly rose, Japanese brands seized the opportunity to offer smaller, reliable fuel-efficient cars while Detroit refused to do so. In fact, Detroit never learned how to produce small cars profitably. These days, they make most of their money on SUVs and pick-up trucks. Today, Detroit’s US market share is down to just 40%.

Toyota is now the world’s biggest automaker, a status that General Motors had enjoyed for 77 consecutive years. And just as success blinded GM to a change in the times, so it has done the same to Japanese brands. Just-retired Toyota chieftain Akio Toyoda dismissed EVs as over-hyped and repeated the myth that a shift to EVs would actually increase carbon emissions because of the increased need for electricity, which is largely produced by fossil fuels.

Toyoda’s successor, Sato Koji, told the press at his first meeting with them, “We will thoroughly implement electrification, which we can do immediately.” But we’ve heard similar comments over the past year or two and many auto analysts remain skeptical on grounds of both intentions and capabilities. Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts that, come 2030, EVs will comprise a minuscule 2.5% of the total number of passenger vehicles on the road in Japan, compared to 13% in the US and 23% in Germany.

The Japanese automakers seemed to have assumed that they could pursue their emphasis on hybrids and that, if and when the time came to focus on EVs, they could play catch-up. But it is not clear that catchup will be easy, not just because of brand loyalty issues, but also due to internal corporate culture. It is common among highly successful companies for managers and engineers to become too attached to the business model and technology that brought them success in the first place. They often look down on seemingly less sophisticated technologies that end up overthrowing their dominance. The famous book, The Innovators Dilemma, details this pattern in industry after industry. The Economist, in a piece headlined “How Japan is losing the global electric-vehicle race,” reported that, “Engineers at Japanese firms that fine-tuned complex hybrids were also unimpressed by EVs, which are simpler mechanically.”

Japan’s government and automakers have become stubbornly obsessed with the romance of cars powered by hydrogen fuel cells rather than batteries, part of a notion they hype as the building of a hydrogen society. In fact, the government throws more subsidy money down the sinkhole of fuel cell cars than it devotes to EVs. The country has been working on fuel cell cars for years and years, and results have consistently fallen far short of puffed-up forecasts. Prior to the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, Tokyo claimed that the games would be powered by electricity produced by fuel cells using green hydrogen and that participants would be transported by cars running on hydrogen fuel cells. In a comment typical of the bombast, former Tokyo Governor Masuzoe Yoichi boasted, “The 1964 Tokyo Olympics left the Shinkansen high-speed train system as a legacy. The upcoming Olympics will leave a hydrogen society as its legacy.” In reality, instead of the whole Olympic Village, only one building was fueled by hydrogen. And only a few buses on short routes were powered by fuel cells. The Mirai, Toyota’s fuel cell car, has sold only 22,000 cars worldwide since its introduction almost a decade ago.

Autos Just Part Of A Common Pattern

Far from being unique, the reversal of fortune bringing down seemingly invincible giants has been seen in industry after industry. Typically, when an industry is new, a host of companies enter the field. Between 1895 and the 1930s, more than 1,300 car companies were born and died in the US alone, some running cars on steam, some burning wood or gasoline, and, ironically, still others using batteries. Once a dominant technology emerged, the field narrowed to the Big Three and a few niche players. In industries where rapid technological shifts are frequent, like electronics, the rise and fall of companies is equally frequent. In fields, like autos, where the fundamental technology remains stable for a long time, a few companies can dominate for decades.

However, when there is a big, abrupt shift in technology and market conditions that undermine the existing business model, the dominant players are likely to stay with the old technology and business model for too long because they underestimate the shift in front of their eyes, That gives room for new challengers to rise. Back in the 1960s-70s, such shifts enabled Japanese companies to displace US giants in several important fields. In TVs, the Japanese moved to solid-state technology ahead of their US counterparts. In steel, as US companies stuck with the older open-hearth technology, Japanese companies moved to the more efficient basic oxygen furnace. In computer memory chips (DRAMs), Japanese companies produced more densely-packed chips, the 16K and 64k generations, at a lower cost ahead of the US leaders. Rather than perceiving the reality of their strategic blindness, Americans seized on various practices by Japan to claim the main, or even sole, explanation was alleged cheating by Japan, a charge leading to decades of trade friction.

Today, Japanese oligopolists wear the same sort of perceptual blinders. Japanese steel companies lag in using electric arc furnaces, causing them to emit more greenhouse gases than their international competitors. They create a stunning 14% of Japan’s total carbon emissions.

Japanese firms suffer an additional problem hobbling their ability to adapt to change Due to almost exclusive promotion from within the company, executives find it hard to abandon a product or technology championed by the seniors who sponsored them. That would feel like a betrayal. It’s one of the reasons companies like SONY lost billions of dollars over many years by sticking with TVs for far too long. Can new CEO Koji stray very far from the strategy trumpeted by Toyoda?

It is not foreordained that Toyota, Honda, et. al. will fall victim to this common pattern. But time is not on their side.

Thanks for an excellent analysis, as always. However, one small correction: "The Mirai, Toyota’s fuel cell car, has sold only 11,000 cars worldwide since its introduction almost a decade ago." That is the Mirai's sales figure for the US, not worldwide. Worldwide, Mirai has sold 22,000 cars, not impressive at all, but twice as many. https://global.toyota/en/company/profile/production-sales-figures/202211.html

Richard, this is a brilliant piece, absolutely in line with The Innovator’s Dilemma. Your data-driven arguments are much appreciated. How many other successful companies face similar risks because they attempt to protect their past successes? The EV shift is one cataclysm; AI is another, where its effect on advertising holding companies will be dramatic (their business model involves being paid “by the head” rather than “for the work.” When AI eliminates the “heads,” what then?