Contrarian Musings: Could LDP Defeat Improve Prospects for Reform?

The DPFP-LDP Negotiations on Tax Relief For Households

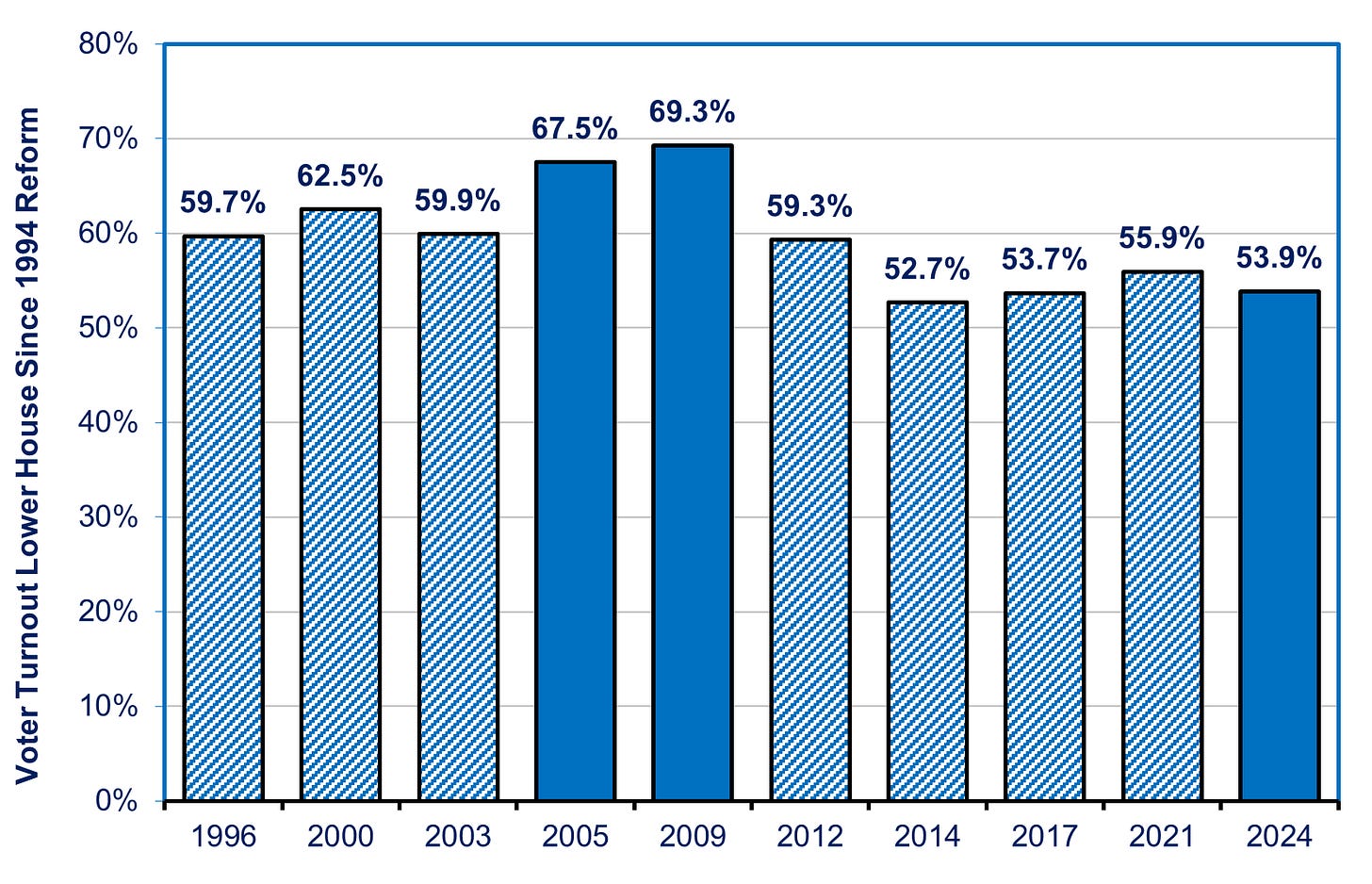

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1263233/japan-voting-rate-house-of-representatives-elections/ Note: The big turnout years were 2005 when Junichiro Koizumi ran against anti-reformers within the LDP, and 2009 when the DPJ ousted the LDP. 2009 was the highest since the election system was changed in 1994.

The conventional wisdom is that the defeat of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) weakens the prospects for economic reform, at least for a while. That’s because reform can only be done via a strong Prime Minister committed to reform. With a weak Prime Minister, the bureaucracy will fill the power vacuum, and since the Ministries disagree among themselves, there are a lot of “veto points” hindering any initiative. Hence, goes the argument, inertia will rule the day.

There’s a lot of truth in this argument, particularly in the near term. Nonetheless, if the LDP's weakness continues through next year’s Upper House election, and beyond, increased competition among the parties could make them more sensitive to voter needs. This, in turn, opens the door for more economic reform. Here’s the thrust of my argument, as I discuss in Chapters 16 and 18 of The Contest For Japan’s Economic Future.

On the one hand, Japan has seen a lot less real reform in the past decade than has been claimed for it, even though Shinzo Abe was one of the strongest Prime Ministers in modern history. He faced neither a viable opposition party nor any strong opponents within the LDP. Moreover, the LDP-led coalition enjoyed the immense power of a two-thirds majority in the Lower House. Yet, for all his talk about “third arrow” reforms and “no sacred cows,” he declined to spend his abundant political capital on reforms that hurt powerful vested interests. After all, what is the incentive for the LDP to step on its supporters’ toes when it can remain in power without doing so, and when rhetoric can substitute for reality on election day? When those who are disenchanted just stay home? (The LDP got fewer votes in Abe’s triumphant return in 2012 than in its landslide defeat in 2009.)

On the other hand, many of Japan’s most impactful reforms have occurred at times when the LDP had good reason to fear being ousted, or when the opposition had control of the Upper House and the LDP controlled the Lower House. The establishment of universal health care in the 1960s and the pollution Diet of 1970 both took place when the LDP had to fear the rising power of the Communists and Socialists in the cities they governed, and when astute observers feared the LDP could lose power on a national level.

Major financial reforms were enacted in 1998 when Japan’s growing banking crisis enabled the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) to gain control of the Upper House in the summer elections. That prevented the LDP from just bailing out the banks with taxpayer money but no real reform. An alliance of reformers in the LDP and DPJ conditioned a bailout on a new law that took supervision of the banks away from the Ministry of Finance (MOF), which had spent years denying the growing crisis. The law created the Financial Services Agency (FSA) to take over supervision. The reformers also passed a law making the Bank of Japan independent of the MOF.

It was under DPJ rule in 2009-12 that Tokyo established the policy of raising the minimum wage to ¥1,000 within a decade, a policy that has done so much to raise wages for Japan’s lower income quintiles. Abe adopted that policy in 2016 when the Bank of Japan finally recognized that monetary policy alone could not even conquer deflation, let alone revive economic growth.

With that history in mind, let’s look at a current tussle around a major tax reform as Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba tries to form a workable government. This creates the possibility of reversing the LDP's policy of shifting money from people to corporations. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida had conspicuously vowed to implement such a reversal as part of his “new form of capitalism.” Yet, he declined to take any significant steps. Now, the LDP's loss opens up new opportunities.

DPFP Pressures Ishiba on Lowering Taxes for the Less Affluent

Since the LDP-Komeito coalition lost its majority in the Lower House and none of the opposition parties were willing to join the government, Ishiba has been holding talks with the Democratic Party For the People (DPFP) to get the DPFP to support LDP initiatives, like the budget, on a case-by-case basis. The DPFP is using its leverage to try extracting concessions from the LDP on about 15 economic issues. The most famous are tax cuts that would significantly increase real disposable income and the talks seem difficult. Focusing on people’s incomes was what enabled the DPFP to quadruple its seats from 7 to 28 and become the fourth-largest party. Led by a former official of the Finance Ministry, the DPFP is more conservative than the much bigger Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP)—148 seats—and is aligned with Rengo, Japan’s biggest labor union federation.

One DPFP demand is that the government raise the tax exemption level—effectively a no-tax bracket on personal income or social insurance premia—from the current ¥1.03 million ($10,000 in Purchasing Power Parity dollars) to ¥1.78 million ($18,000). (Purchasing Power Parity translates currency rates at levels that properly compare living standards). The DPFP’s second demand is a temporary cut in the consumption tax from 10% to around 5%. A third demand is continued subsidies on gasoline and as well as renewables.

Polls cited by Tobias Harris show broad public support for the DPFP’s economic program. “The public does not think that the DPFP should join the ruling coalition...[T]he DPFP’s negotiations with the LDP and Komeito over taxes and budgets are highly popular, supported by 63% compared with only 23% who oppose these talks...Sankei also found that the DPFP’s call for raising the annual income tax exemption...is backed by a wide margin, with 77.2% in favor to 16.6% opposed.”

According to estimates by the Daiwa Institute of Research, if the income tax threshold is raised to ¥1.78 million, a person earning ¥2 million a year ($20,000 in PPP dollars) would see their combined national and local income taxes cut by ¥82,000 (4% of their total income), a person earning ¥5 million by ¥133,000 (2.6%) and a person earning ¥8 million by ¥228,000 (2.8%). Temporarily halving the consumption tax would put more than ¥12 trillion into consumer pockets, around 4% of disposable income. As the DPFP stresses, raising consumer spending power is indispensable to restoring healthy GDP growth.

The DPFP also contends that raising the exemption to ¥1.78 would help growth by leading more people to work longer hours. The logic is that many people don’t want to earn more than ¥1.03 million because then they’d have to pay social insurance premia. People need to earn Y1.3 million to get their disposable income back to where it was just below ¥1.03 million. Reforms in 2018 eliminated this problem vis-à-vis the income tax. However, the same remedies were not applied to social insurance premia, where the drop-off occurs at ¥1.06 million (see chart below).

Source: https://www.tokyofoundation.org/research/detail.php?id=966 Note: See text for further explanation.

This flaw leads some people to work fewer hours than they’d like. In 1995, when the ¥1.03 million level was set, the minimum wage was ¥611, so it took 1,695 hours to earn ¥1.03 million. Today, with the minimum wage at ¥1,055, it only takes 976 hours. This is a particularly tough problem for the self-employed, who cannot easily calculate how much they will earn for the year if, around September or October, they approach ¥1.03 million. Should they stop soon, or keep working in hopes of reaching ¥1.3 million? The Labor Ministry says that 15% of women who decreased their hours did so because of the ¥1.03 million barrier. It’s not clear if this is accurate or an underestimate.

Critics claim that elevating the tax exemption level is unaffordable because it would cost national and local governments an estimated ¥7 trillion in revenue. That’s 20% of the revenue from personal income taxes and 6% of all tax revenues in 2022. The DPFP insists that it’s up to the LDP to find a way to finance the tax cuts. I’d argue it should be done by rolling back some of the big tax cuts given to corporations, as detailed below.

Reversing the LDP's Transfer Of Income From People to Corporations

For decades, the LDP has been transferring income from people to corporations via the tax system. In 1994, the consumption tax took away 2.4% of households' net disposable income; now, it takes away 9%. Conversely, in 1994, Japan’s 2 million corporations paid half of their profits in taxes; now it’s just 15% (see chart below). The rationale was the trickle-down theory that cash-rich companies would boost growth by hiking capital investment and raising wages. It never happened.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/corporate-tax-rate, https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/budget/budget/fy2024/02.pdf, https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/data/kakuhou/files/2022/tables/2022i5_en.xlsx

In 1990, just before the lost decades, current profits amounted to 8% of GDP; today, mainly due to wage suppression, the profit share has doubled to 17%. By contrast, in 1990, corporate income taxes amounted to 4% of GDP; today it’s just 2.2% (see chart below). Kishida had mooted rolling back some of these cuts to pay for doubling defense spending, but quickly caved when big business protested.

Source: OECD at https://tinyurl.com/28cv5j84

A Possibility, Not A Forecast

There are, of course, a lot of reasons the rosy scenario could fail.

Firstly, were the voters only giving the LDP a temporary spanking? Or, is this a more lasting disenchantment spurred by economic malaise? Next summer’s Upper House election is the next big test.

Secondly, can the opposition earn credibility among voters by presenting a compelling program, and, if so, will voters give it a second chance after the DPJ’s failure in 2009-12. In this election, the biggest opposition party, the CDP, focused mostly on the LDP's scandals, and failed to present a clear program to address concerns about living standards. It looked more like a gadfly than a government in waiting. In 2005, Junichiro Koizumi brought out the disenchanted floating voters by presenting himself as a strong reformer, as did the DPJ in 2009. Since then, these independent voters have stayed home, including this year. That lets the LDP rule by default (see chart).

Thirdly, not all changes spurred by competition constitute reform. Some represent the opposite. For example, under Kakuei Tanaka and in the aftermath of the 1973-74 oil shock, the LDP adopted many regressive steps, steps that ultimately led to the lost decades. One was the Large-Scale Retail Store Law, which preserved small, inefficient mom-and-pop retailers and kept consumer prices high. Another was large bailouts for zombie firms, which led to the bank debt crisis. This year, the DPFP is supporting continued subsidies for gasoline.

Finally, while competition creates the political incentive to genuinely improve the economy’s performance, it still takes a strong PM with a solid majority in the Diet to override vested interests.

Think of this post, not as a forecast, but as a map to judge whether forthcoming events portend more hollow promises, or whether they increase the chances for genuinely substantive policy improvement. The first test is the outcome of the LDP-DPFP negotiations over tax cuts. The talks seem difficult.

.

Thank you for the detailed analysis and explanation. Having lived in Japan for so long, I know not to hold my breath, as the prospects for meaningful change are probably still pretty slim. I suspect that the recent election was, as you suspect, more of a spanking than a reprieve for the LDP.

The current corporate tax policy seems flawed, as the trickle-down benefits are likely to remain elusive.

As for the 1.03 million yen problem, choosing another number such as 1.78 million yen as the threshold is likely to be only a temporary solution. The tax code for relatively low-wage earners seems far too complicated and creates perverse incentives that end up thwarting productivity and squeezing the average family's household budget.