Gyrations in Yen and Stocks: How Much Impact?

I’m Cited in the New York Times and Washington Post

Source:

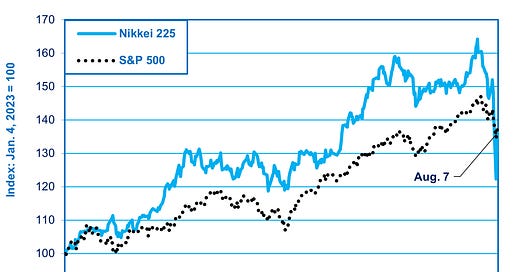

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

“The stock market has predicted ten of the last five recessions,” is one of the most famous quips in economics. It’s something to keep in mind when looking at today’s market turbulence. When the yen leaped in value, Japanese share prices plunged 20%(!) from their July 31st level, US employment numbers looked weak, and the American stock market fell 6% between July 31st and August 5th. This provoked a lot of loose talk about the dangers of a US recession. If that were really in the offing, it would set back any hope of a near-term recovery in Japan. Fortunately, it seems very unlikely to be the case. When there’s a sudden crash like this—rather than a slower grind downward—it’s often just a stock market phenomenon, as in 1987, and not a harbinger for the real economy. Already, American share prices are almost back to where they were on August 4th and two-thirds of the way back to the July 31st level (see chart above).

Japanese share prices, on the other hand, suffered a much nastier crash, one that sent them back to a level first reached in May of 2023! Still, they are also recovering and have erased about half of that 20% nosedive. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has helped calm markets by promising no more hikes in interest rates as long as financial markets remain fragile. It was, after all, the BOJ’s 0.25% hike in the overnight interest rate that triggered the gyrations of the yen and stocks.

Even if Japanese stock prices remain weak, it would no more be the harbinger of an economic slump than its stellar rise earlier this year was, as all too many claimed, a sign that “Japan is back.” As I told the Washington Post, “Stock prices in Japan have surprisingly little impact on the real economy. That’s because companies are cash-rich and don’t need to use the stock market to finance corporate investments. Moreover, because households invest so little in stocks and share prices, they have little effect on consumer wealth and spending.”

The Impact Of A Stronger Yen

The yen rate is different from the stock market because it affects the volume and price of exports and imports and consumer spending power. A lasting recovery in the value of the yen—if it really happens— would have a substantial impact on the real economy, mostly positive. A stronger yen would help reduce the price to consumers of import-intensive items like food and energy and thus help households' real incomes. That’s positive for consumer spending. However, to see the prospects for spending, we also have to look at the wage and inflation picture since households are strapped for cash. As I told The New York Times, “Consumer demand is weak. The savings rate has fallen to zero. People are having to spend their income.” Moreover, we don’t yet know how much the big shunto wage hikes—which apply to just 16% of the labor force—will spread to the rest of the economy. Last year was a big disappointment. “Signs point to this time being better,” I told the Times. “But by how much? We don’t know yet.”

I also told the Times that we don’t know how wage hikes will translate into inflation. “To presume companies will be able to pass on wages — the BOJ is seeing things through a prism that tells them what they want to see.” So, we don’t yet know whether the BOJ was right to raise interest rates.

One might think that a stronger yen would hurt the real economy because it would reduce the profits of the big multinational companies that dominate the stock market. That’s why the rise in the yen’s value triggered the 20% correction in stock prices. One might think that reduced profits would translate into reduced investment, thereby hurting the real economy, But that’s not the case. Big companies are loaded to the gills with cash, but they cannot find profitable ways to invest all that cash at home. Corporate cash flow exceeds investment by up to 8% of GDP, or more, per year (see chart below). If rising profits don’t boost investment, then reduced profits are unlikely to reduce it.

.Source: https://www.mof.go.jp/english/pri/reference/ssc/historical/all.xls

Why the Yen Is Recovering

There’s a good reason why I don’t make forecasts on the yen. If the pros betting hundreds of billions of dollars get it wrong so often, what chance have I? The assorted factors underlying the ups and downs of the yen are too unpredictable—as is the market’s response to them. That’s why, at the beginning of the year, lots of top forecasters saw the yen hitting ¥125 by December, and then, more recently, we saw forecasts of ¥170. And now we are again hearing ¥125. So, I content myself with trying to explain the past and present rather than pretending to read tea leaves that don’t yet exist.

What sent the yen higher was an overly large reaction to relatively small changes, a computer-driven cousin of old-style “runs on the bank” that you can see in movies from the 1930s. The jargon, in this case, is terms like “squeezing the shorts” and “unwinding the carry trade.” Here’s what happened.

The yen hit its weakest point on July 10th at nearly ¥162/$. Then, a series of events set off a reversal of the trend in how investors bet on the yen’s future direction. One event, on July 10th, was another bout of Finance Ministry currency intervention of the type that had previously failed to have more than a temporary effect. Then, there were increasing expectations that the BOJ would raise interest rates at its July 31st meeting, expectations fed by leaks from the BOJ. By the time the BOJ meeting actually occurred, the yen was at ¥153, almost ten points stronger than it had been just a few weeks earlier (see chart below)

.Source: Wall Street Journal

All of this started causing big losses for all those traders who had bet boatloads of money that the yen would continue to weaken. On commodity markets, traders had engaged in record amounts of contracts where they “sold the yen short,” in the same way that they can sell stocks short. That is, they sold the yen before they owned them, expecting to buy them when the price was lower. When, instead, the yen grew stronger, they had to quickly reverse themselves and buy yen now, lest their losses mount even higher. This buying sent the yen even higher, forcing still other investors to do the same. On top of this, investors had borrowed a whopping $1 trillion in the so-called “carry trade.” That is, they borrowed yen, where interest rates are on the floor, in order to invest in assets where rates are higher, e.g., the US or Europe. When it came time to pay back the loan, they expected it would be cheap to buy the needed yen. However, when the yen reversed, they suddenly faced the prospect of having to pay such a high price in yen as to wipe out the profits they expected to make from the differential in interest rates. So, they, too, had to buy yen earlier than expected to head off losses. As they did, that, too, sent the yen higher and forced other investors to act in the same manner. In short, people sold today because others had sold on the day before, and their own sales caused still more investors to sell the next day.

When the BOJ raised interest rates sooner than most expected, and US employment numbers announced the same day were weaker than expected—raising expectations of a September cut in US interest rates—the whole process accelerated. All other things being equal, a narrower gap between American and Japanese interest rates means a stronger yen. That sent the yen all the way to ¥144 by August 4th. But, as I write this, the yen is giving back some of its gains and is now around ¥147.

The Future

I certainly have no idea where the yen will be in six months and neither do the trading and forecasting pros. The uncertainty level is very high. In the short term, traders bet, not so much on fundamentals, but “the trend is your friend.” When the trend reverses, so do they, and momentum can sometimes overshoot in one direction or another.

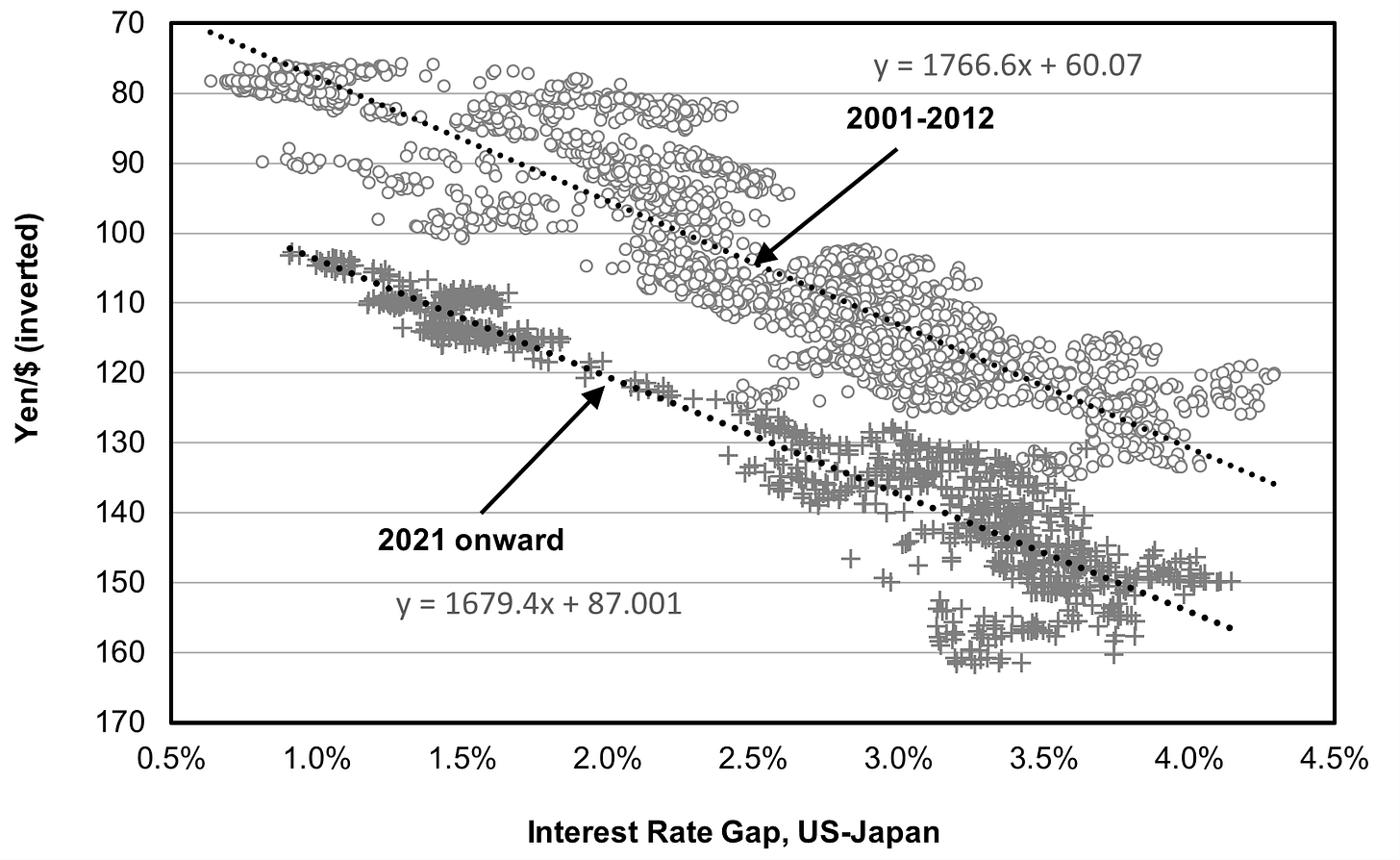

Over the long haul, to be sure, fundamentals are critical. It is fundamentals—Japan’s economic weakness—that explain why, despite short-term fluctuations in interest rates and other factors, the yen is persistently weaker than it was two decades ago. At any given gap between American and Japanese interest rates, the yen is about 25 points weaker than in 2001-12 (see chart below).

As to the next few months, smart authorities differ. Citibank believes that the unwinding of the carry trade is out of the danger zone. Others told the Financial Times they still see more turbulence on the near horizon.

As to the future, here’s one indicator to watch. For the past three years, until this spring, the gap between American and Japanese 10-year government bond interest rates has been an excellent forecaster of the yen rate. Most of the time, the actual yen was in a range 4 points above and below the forecasted level. Beginning in the spring, other factors discussed in this post overwhelmed the interest rate factor. The gap between the actual and forecast yen rose to 20 points (see chart below). Now the gap is back down to 10 points. Whether that gap shrinks further in the next several months will be illuminating.

On some days on amazon.co.jp

Thank you for another concise, easy-to-understand explanation of what is happening in the forex market. By the way, I noticed your comments published in the New York Times.

Why are Japanese companies with large cash reserves finding it so difficult to put that money to work?

What are they likely to do with their excess cash?