How China’s Troubles Could Hurt Japan

From Economic Slowdown To A Cycle of Supply Cut-Offs

Source: OECD at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIVA_2021_C3 and https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIVA_2021_C2 for export and assorted sources for sales of foreign affiliates

Notes: Exports are the value-added portion of total exports as explained in the text, 2018 data; percents refer to value-added exports as a share of GDP

If the economists cited by Reuters are right, China’s travails could send Japan into a mild recession. These economists say that, depending on the severity of any slowdown in China, it “could knock 1-2 percentage points off Japan's annual growth.” But the immediate impact is just that: just the immediate impact. Looking further down the horizon, Japan’s economy will be hurt by a lasting deceleration in Chinese growth, the techno-war and geopolitical tension between China and the West that has led to de-risking, and Chinese intellectual property theft from Japanese firms located inside China.

The biggest immediate impact would be a hit to Japan’s exports. Value-added exports to China—i.e., not counting the portion of Japan’s exports made up of imported supplies like oil and parts—amount to a hefty 3.7% of Japanese GDP. Every 10% decline in those exports directly reduces Japan’s GDP by 0.4%, not counting multiplier effects. Now consider that Japan’s exports to China fell more than 10% during the first eight months of this year. On top of that, for every 1% decline in Chinese GDP growth, there is a 0.3% decline in GDP in the rest of Asia because China imports less from them. That, in turn, means Japan exports less to the rest of Asia. Value-added exports to the rest of Asia add up to 3.3% of Japan’s GDP.

Then there are the cycles of the emerging techno-war. The cut-off of critical technologies to China will add to its economic woes, and Beijing has already blamed its woes on an alleged effort led by the US to contain it and prevent its further development. The Chinese Communist Party’ (CCP) longstanding “we’re under attack” card resonates with the public. While many Japanese firms operating in China fear the US may push too hard, as do some Europeans, ultimately, Japan, the US, and Europe share common interests vis-à-vis China. In 2020, as part of a supplementary budget, Japan spent a small amount of money subsidizing firms to move some of their operations out of China into other countries as part of a “China Plus One” posture.

The third point of vulnerability is a loss of revenue by Japanese companies and exposure to corporate espionage.

Japan’s Vulnerability On the Export Front

Except for Japan’s auto industry, which reaches customers primarily via joint ventures in China, Japan’s exports to China dwarf sales by its affiliates there. By contrast, German companies rely much more on sales of affiliates. The same is true of the EU as a whole. For US firms, exports, and affiliate sales are about half and half (see chart at the top of the blog).

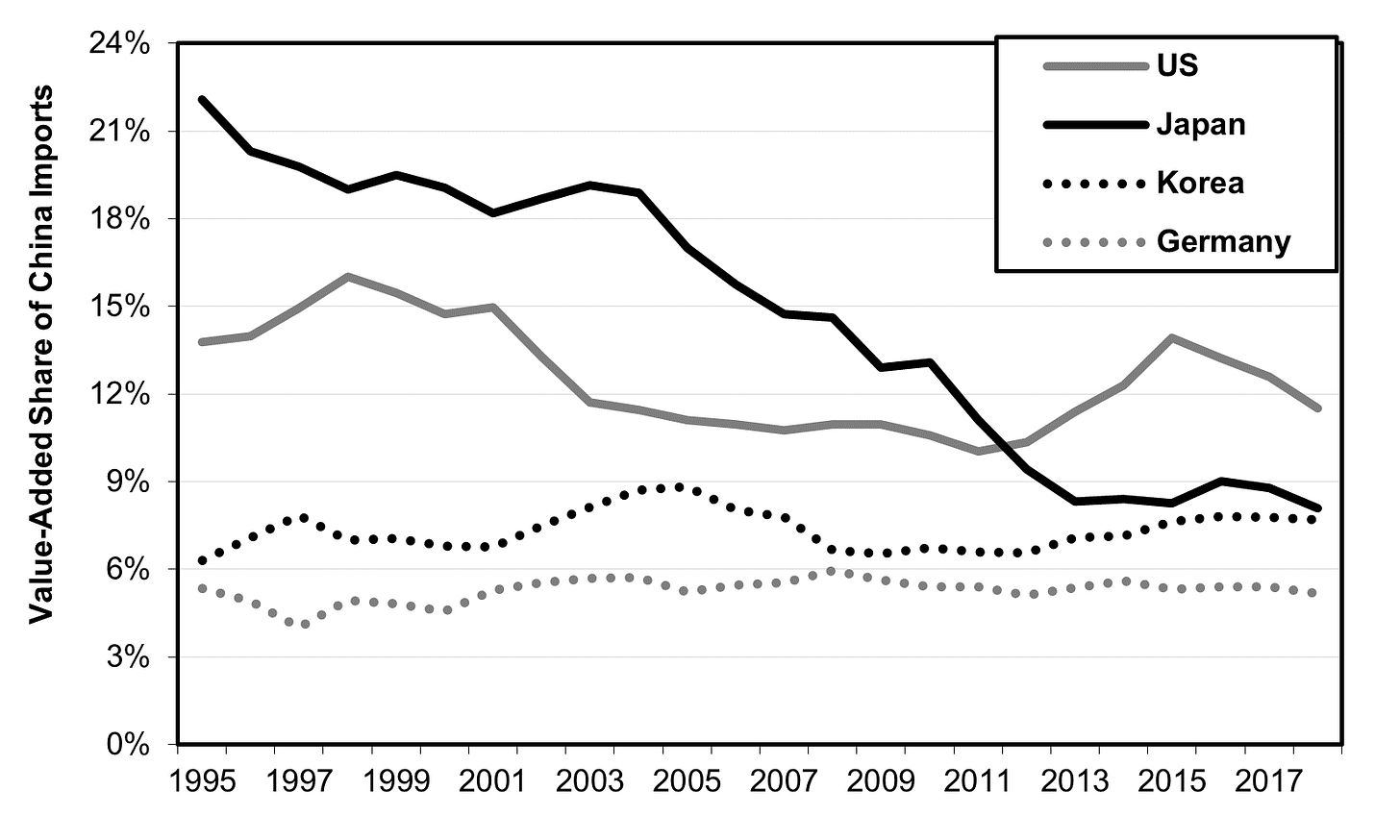

Those exports have been under downward pressure for years before the current downturn. For one thing, global imports as a share of Chinese GDP initially soared, but then reached a peak as China industrialized at 28% of GDP in 2005. By 2022, they were down to 17%. On top of that, Japan has been losing market share in China relative to competitors like Korea. So, Japan is getting a smaller slice of a shrinking pie. Let’s look at the details.

Imports of machinery and parts from more advanced countries have been indispensable to China’s modernization of those industries. And China’s own exports have long been the leading edge of its rise up the value ladder. Consequently, a big portion of the value of China’s exports were imported components. As we see in the chart below, the import content of China’s exports of information industry exports peaked at 48% of their total value in 2004 and has since declined to 31% as of 2018 (latest available data). That’s the shrinking pie.

At the same time, Japan’s share of the total foreign content (value-added exports as a share of Chinese imports of manufactured goods) has also been shrinking (see chart below).

A smaller slice of the shrinking pie means that, in absolute numbers, Japan’s value-added manufacturing exports to China shrank a bit from 2011 to 2018 (see chart below). China’s economic and political troubles will likely make Japan’s export difficulties even worse. Korea is even more vulnerable, with its exports to China adding up to 8% of its GDP (see chart).

Japan Already Slowing FDI Into China

Given the combination of a sluggish economy, the ongoing techno-war, and corporate espionage by Chinese firms and the government, and even fears of the unthinkable—a Chinese attack on Taiwan—it’s no wonder that Japan’s FDI into China has already slowed down. More companies say they are going to reduce their investment or withdraw altogether.

In a September survey, only 20% of major corporations said that they would expand operations over the next 2-3 years, a lower share than any other of 18 major countries except Hong Kong and Russia. 5% would reduce them and 75% would keep them at current levels. Over the coming decade, only 10% of respondents would expand operations, 48% would keep them at the current level, 7% would lower them, and 34% did not know. When asked why China risks are increasing, 82% cited U.S.-China trade friction, 78% pointed to the bursting of the real estate bubble and 65% feared a possible Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

These days producing in China to sell back to Japan or third countries has been replaced by sales to Chinese business and household customers. The latter reached a peak in 2020 and has since shrunk. In January-March of this year (latest available), global sales of manufacturing affiliates were down 24% from the year before. Some of this is due to Covid. Surprisingly, sales of autos, due to a lack of EVs, were not meaningfully worse than other products. Still, few Japanese business leaders expect sales in China to grow again at past rates and may not even grow as fast as sales in other countries for the next few years (see chart below).

Source: https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/editorcharts/qmyvmoxexvr/index.html, https://www.meti.go.jp/english/statistics/tyo/genntihou/index.html

Already, the China-bound share of Japan’s global FDI has slid from its 2012 peak at 9%. By 2022, it was down to 7%, and looks like it will dwindle even more (see chart below). Of course, that means companies will lose some business, but staying would entail even greater costs, from intellectual property theft to arrests of personnel.

Source: https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/statistics/data/country1_e_22cy.xls

This decline is not due to any disenchantment with Asia. The share going to the rest of East Asia has remained the same (see chart below).

The Techno-War and De-Risking

Not just Japan, but all nations will inevitably be caught in the cross-hairs as technology tension grows between China and the West (including Japan in this term). That will end up hurting economic growth for all, but both sides feel compelled to act as they do. The West, including Japan, is cutting off China from some key advanced technologies, primarily for security reasons, but in ways that will inevitably impact China’s economic growth potential. Japan joined the US and Europe and China warned of retaliation against Japan.

China is continuing to cut off exports of critical products, partly as a pressure point on unrelated security issues, and partly in response to moves by the West. For example, in July, Beijing announced that it would restrict exports of gallium and germanium, two metals vital to making computer chips, electric vehicles, and telecommunications equipment. It is also considering restricting exports of rare earth processing technology, another area where it dominates something vital to a host of core products (although its share has been reduced by US efforts.) There is fear that China will “weaponize” its dominance in certain minerals critical for assorted clean technologies. These minerals exist elsewhere but there is an economic cost to diversifying sources. Still, Japan was the first country to sign an agreement with the US to cooperate on critical minerals for EVs.

Such cutoffs by Beijing began long any actions by the US, Europe, and Japan. In 2010, when China raised a ruckus over Japan’s decades-long control of the Senkaku Islands, it cut off shipments to Japan of rare earth metals vital to the production of computer chips (China has a 90% share in these rare earths). It cut off imports from Australia when the latter asked for an investigation of the origins of Covid. China’s domination of assorted minerals critical to electric vehicles and solar power is also causing other nations to diversify their supply.

Other nations became alarmed in 2015 when China announced a Made in China 2025 program to gain independence, and even supremacy, in a variety of leading technologies. As a result, China talked about it less but continued the effort, albeit with disappointing results. A report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) suggests a major turning point came in 2018 when the US denied exports of vital products to China’s second-largest telecom company, ZTE, because it repeatedly violated contracts not to sell certain equipment to Iran. Not only did Xi Jinping personally call Donald Trump to prevent ZTE’s bankruptcy, but efforts like Made in China 2025 and others took on a vital security role in the eyes of China’s leaders. In a speech at the National Peoples Congress, one leader declared: “The U.S. ban on ZTE fully demonstrates the importance of independent, controllable ‘core-, high-, and foundational’ technologies. In order to avoid repeating this disaster, China should learn its lesson about importing core electronic components, high-end general-purpose chips, and foundational software.”

A turning point came last October when the US cut off China from certain advanced chipmaking technology and Japan and Europe cooperated with it. CSIS points out that this represented a fundamental shift. “First, rather than restricting exports...based on whether the exports were related to military end uses or to prohibited end users, the new policy restricted them on a geographic basis for China as a whole. Second, previous U.S. export controls were designed to allow China to progress technologically but to restrict the pace so that the United States and its allies retained a durable lead. The new policy, by contrast, actively degrades the peak technological capability of China’s semiconductor industry. Leading Chinese semiconductor firms such as Biren, YMTC, SMIC, and SMEE have all been set back years.”

In one ominous sign of the times, Honda launched a secret contingency plan to see what it would take to build cars with as few parts from China as possible, even though almost a third of its global sales are made in China.

https://thediplomat.com/2023/10/dont-worry-about-chinas-gallium-and-germanium-export-bans/ This writer explains that the ban on rare minerals by China will only have short term effects. My question: if China is slowing, shouldn't Japan redouble efforts to increase exports to other markets outside Asia, such as Latin America and Africa, where growth is high? Do you see any signs of this?