Japan Is Joining “De-Risk From China” Coalition

Avoiding Disaster Of Either Pole: “Decoupling” or Submitting To Economic Coercion

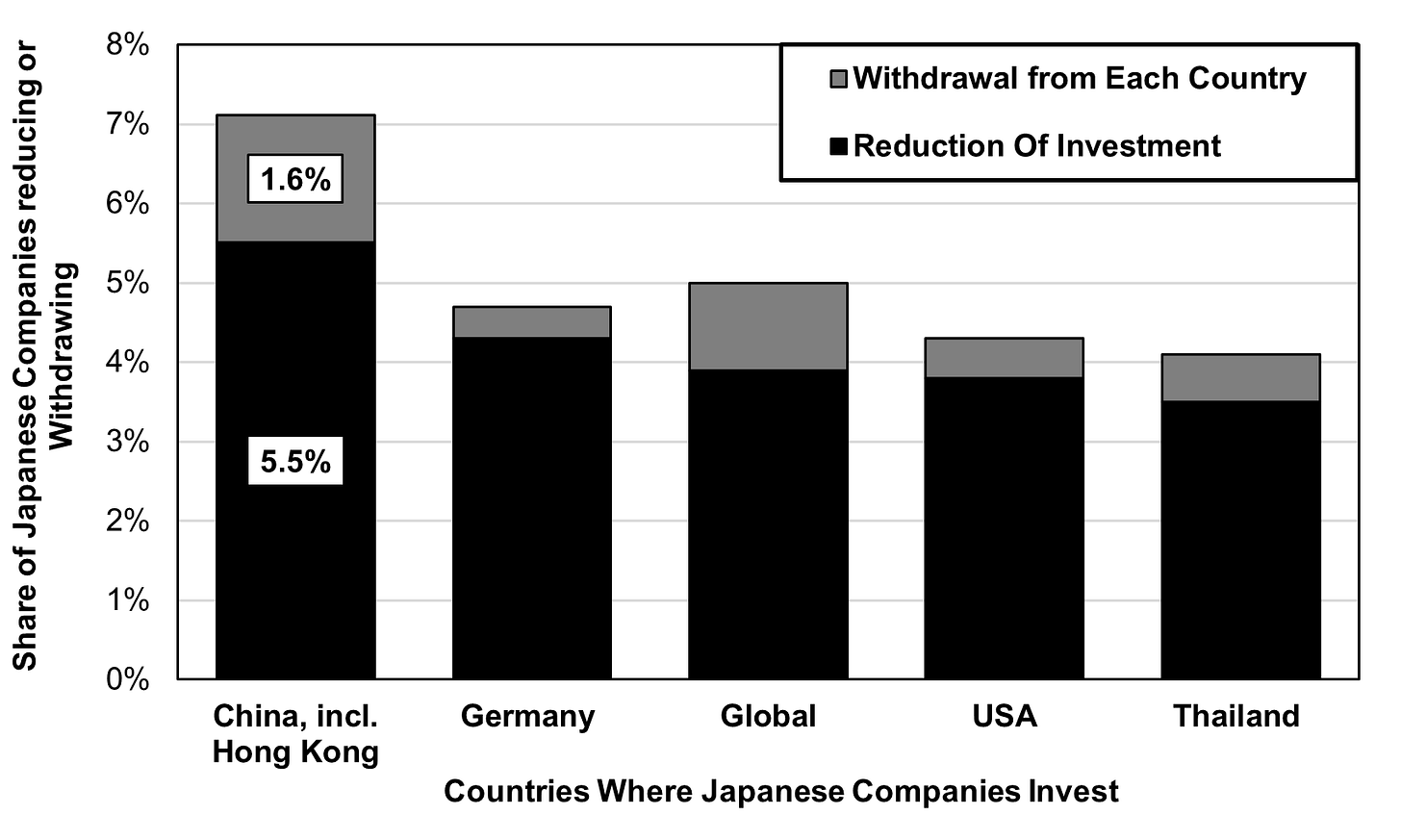

Source: https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/survey/pdf/2022/rp_global2022.pdf

Note: Withdrawal includes moving to another country

Step by step, Japan’s government and companies are joining their American and European counterparts in a “De-Risking” policy toward China. This goes beyond the normal pullback occurring due to China’s economic slowdown, wage hikes, or other natural economic causes. Some de-risking is a response to China’s geopolitical actions that go far beyond the understandable ambitions of a rising power, including seizures of islands belonging to other countries. Then there are the years of corporate espionage, requirements that foreign companies transfer technology to Chinese firms, and discrimination in procurement. This is now exacerbated by police raids on foreign companies and arrests of foreign nationals, including 17 Japanese so far, on charges of espionage where the definition of the latter is unspecified in a new, harsher version of the law. And finally, Beijing is pressuring foreign companies to let Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cells participate in management decisions. In 2018, CSIS reported, the US-China Business Council noted that certain state-owned enterprises (SOEs) involved in joint ventures (JV) had asked some of their foreign partners “to allow critical matters to be approved by the party organization before they are presented to the board.” The European Commission made similar complaints.

Responding via complete “decoupling”—a Donald Trump term—would mean absolute disaster for all because China and the rest of the world are so interdependent. In the worst case, says the IMF, global GDP could drop by 7%. That’s double the drop from Covid. None of the players, including Beijing, wants to see that. Officials from two different Japanese Ministries told me they don’t see Xi as an irrational adventurer like Putin. But he will test the boundaries and, like everyone else, can miscalculate.

Even though decoupling is out, foreign firms and governments are still less inclined to tolerate China’s behavior than they were when business was booming. Six in ten American companies now expect that sales to China will lag behind global sales over the coming three to five years. So, the midway course is what the Europeans call “de-risking,” a term now adopted by Washington. That means cutting China off from certain key technologies, companies creating substitute sources for key products, etc. A fifth of American companies in China will reduce their presence in the coming few years, according to the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. Two of every five will redirect some investments originally planned for China to other countries. European firms are acting similarly.

Japan is carefully moving along the same lines. As early as 2018, Tokyo joined the US and EU in a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint against Beijing for forcing a transfer of technology. That case is still in limbo. A 2022 government survey reports that only a third of Japanese companies will expand their operations in the coming couple of years, the third lowest among 18 countries, above only Hong Kong and Russia. 5.5% are reducing their operations, while another 1.6% will withdraw altogether (see chart at the top of the post). While it’s normal for a certain number of firms to withdraw as economic conditions change, as we see in other countries, the leap in reductions from China go signficantly beyond that normal churn. This is a structural change.

Between China’s economic slowdown and de-risking, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into China from all countries plunged by 8% in the first eight months of this year, a fall matched only during the 2008-09 global financial meltdown.

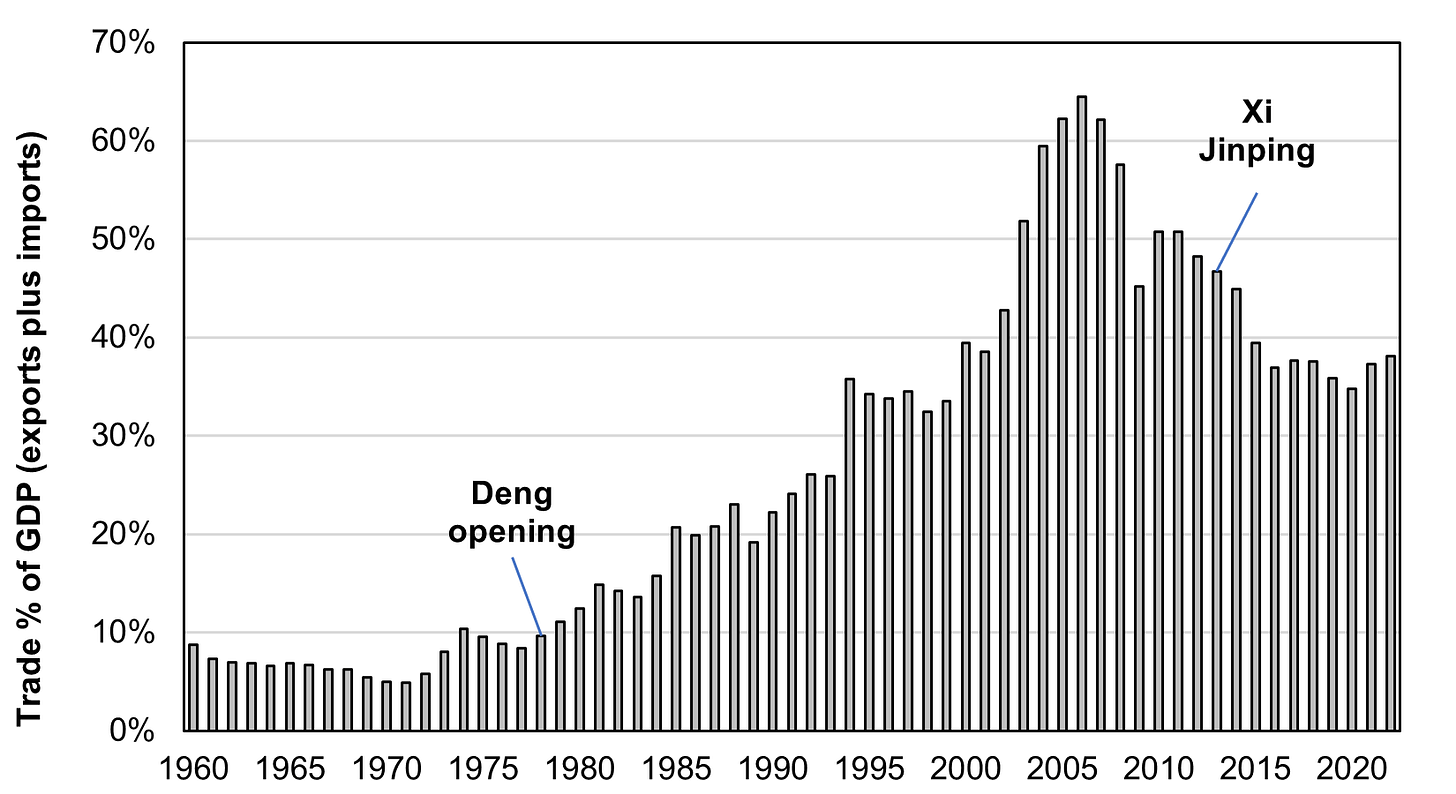

Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740

In the next post, I’ll analyze what all this means for Japan. But, first, let’s look at the consequences that may deter Beijing from going too far.

Xi Driving Away Geese That Laid the Golden Eggs

Xi Jinping may be a good Maoist, but he’s a truly terrible Marxist. Mao famously declared, “Power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Marx would have pointed out that someone must pay for and build that gun. In China, foreign companies are a big part of that “someone.” Without them, there would have been no Chinese economic miracle, and Xi’s geopolitical ambitions would be the stuff of laughter. Yet, in pursuit of political and geopolitical goals, Beijing is alienating them.

Then there is the overseas technology that China still needs, despite the visions of technology independence dancing in Xi’s head. “In the next step of tackling technology, we must cast aside illusions and rely on ourselves,” Xi declared. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 plan calls for the country to become largely self-sufficient and globally competitive in ten advanced manufacturing sectors, including commercial aircraft, robotics, 5G mobile phone communications, and computer microchips. The effort is falling short.

In reality, “Self-sufficiency is a fantasy for any country, even ones as large as the US or China, when it comes to chips,” Dan Wang, technology analyst for Gavekal Dragonomics based in Shanghai, told the Financial Times. As of 2018 (latest data available), nearly 40% of the value-added in all electronic equipment consumed in China consisted of overseas parts and devices.

Xi may believe China has outgrown the need for such international dependence, but he’s wrong. Half of all international trade these days consists of lots of companies in lots of countries playing their role in a global supply chain for any given product. China is just one of 43 countries involved in making Apple’s iPhone. Having become dependent on this system, China cannot turn back time. It can, however, do itself a lot of harm by trying. Xi can have an excessively authoritarian, ideological, and internationally bellicose state or he can have a healthy economy. He cannot have both.

Big structural consequences are already showing up. In recent years, both trade and inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) have fallen as a share of GDP (see chart above and the one below). To be sure, natural economic processes explain much of this decline and they begin before Xi’s ascension. However, a “substantial” share is due to Xi’s policies, says Scott Kennedy, of the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Source: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Perhaps Xi is blinding himself to the consequences of his political strategy. “He may believe that the Chinese market is so large that foreign companies will keep on producing there,” no matter how he treats them, Kennedy told me in a phone interview. It’s often hard to comprehend Beijing’s real intentions because, as Kennedy points out, officials concerned with economic issues—like those who recently tried to woo foreign firms—speak differently than those focused on security. Chinese sources told me that Xi often declines to hear from those warning of the cost of a policy he favors.

At the same time, Xi is blaming others for China’s homegrown economic problems, saying: “Western countries led by the United States have implemented all-around containment, encirclement and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented severe challenges to our country’s development,” Does Xi himself believe it—and does that guide policy—or does he just hope the people will?

China Still Needs Joint Ventures and Exports

All countries, no matter how rich, grow better with more well-managed FDI and international trade. China, still just an upper-middle-income country, needs it even more. Data showing that China leads in patents are misleading because, while the quantity is up, the quality is down (see my last post).

What makes FDI so powerful is its spillover effects. In cross-country JVs in China, the presence of a foreign partner raised not only the JV’s own productivity, but also that of the JV’s suppliers, and even unrelated firms in the same industry (see chart). Just by participating in the economy, companies transfer tacit know-how to their employees, suppliers, customers, competitors, and even unrelated firms.

Source: https://www.nber.org/digest/aug18/spillover-effects-international-joint-ventures-china

Note: Total Factor Productivity (TFP) means the ratio of outputs to all inputs, capital as well as labor.

Partnering with American firms provides twice as much productivity gain, mainly because of America’s lead in getting the most economic benefit from new technology.

When China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000, it had to loosen its requirements that foreign firms invest primarily via JVs. So, firms quickly switched to 100% foreign-owned affiliates (see chart below). It turns out that the looser the JV rule in any industry, the bigger the productivity gains. That’s because, once foreign firms felt more able to protect their intellectual property, they upped their activities in China, automatically leading to more spillover effects.

Source: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24455/w24455.pdf

One study divided China into regions with high, medium, and low levels of FDI. There was a lot of spillover of productivity and growth from the high region to the low region as firms from each region interacted with each other. Studies of foreign trade show similar spillovers.

Hurting China’s Growth

As European companies recently warned, Xi’s actions reduce China’s access to such benefits. In response to corporate espionage, a stunning three-quarters of European companies have segregated Chinese operations from those at global headquarters, while 16% no longer employ any non-Chinese. “These developments come at a considerable cost to companies and to China,” said the European companies, because they “reduced transfer of knowhow.”

All this comes at a time when problems at home make the know-how coming from FDI and trade even more pivotal. China is suffering both a fall in the labor force and limits to investment growth. Consequently, its overall growth in GDP per worker (and thus per capita) depends on growth in Total Factor Productivity (TFP). The latter is how much growth in GDP a country gets for every 1% growth in capital and labor inputs. During 1980-2010, TFP accounted for about 40% of growth in per-worker GDP growth. However, annual TFP growth has plunged from 3.1% a year in the past to only 1.1% during 2010-19, the Xi era (see chart below). Consequently, TFP’s share of overall growth in per-worker GDP fell to just 15%. Normally, as countries get richer, the TFP contribution becomes larger.

Source: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/848481/pdf

Note: Human capital is based primarily on education and skills

Xi’s “Dual Circulation” Campaign

In defiance of these results, Xi is pressing on with a policy Beijing calls “dual circulation.” The notion is to increase domestic demand so as to be less dependent on exports. This is, of course, impossible as long as wages keep being suppressed. China knows it cannot isolate itself but, say experts, wants to reduce its vulnerability to the actions of others. Beijing would argue that Donald Trump’s unilateral tariffs, e.g., 25% on autos, and the continuation of all of them by Joseph Biden, make it necessary to reduce its vulnerability.

One example of the policy is giving financial rewards to companies that substitute domestic technology for foreign technology. Even before Xi’s ascension, foreign companies complained about discrimination in procurement. Under Xi, say companies, discrimination, and cyber-spying have greatly worsened. Many foreign execs have even stopped bringing cell phones into, or out of, China. From time to time, various government bodies concerned with economic policy promise to fix these problems, but usually fail to do so. Perhaps they are sincere—because they recognize the risk of blowback from going too far—but they are up against security-oriented leaders who think China needs to bolster its economic independence via “dual circulation.”

It looks like China’s nationalistic actions and others’ de-risking will each reinforce the other in a vicious cycle. The law of unintended consequences seems to be in play.

Excellent article. The main goal of the CCP is to maintain its power. This was evident in Deng Xio Ping's reforms in 1980, and it remains the same today with the attempt to create a new system of total control over society and business, similar to the Cultural Revolution 2.0. The ultimate aim is to prevent the emergence of independent power centers. Read the additional article on the reasons for China's growth from 1980 to 2012.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/janusz-kowalewski-99b6275_activity-7080401391185260544-qhRs?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios