Xi Reduces Role of Private Firms, Hurts Innovation

Xi Jinping Seeks To Ban “Socialism with Japanese and Singaporean Characteristics,” Part II

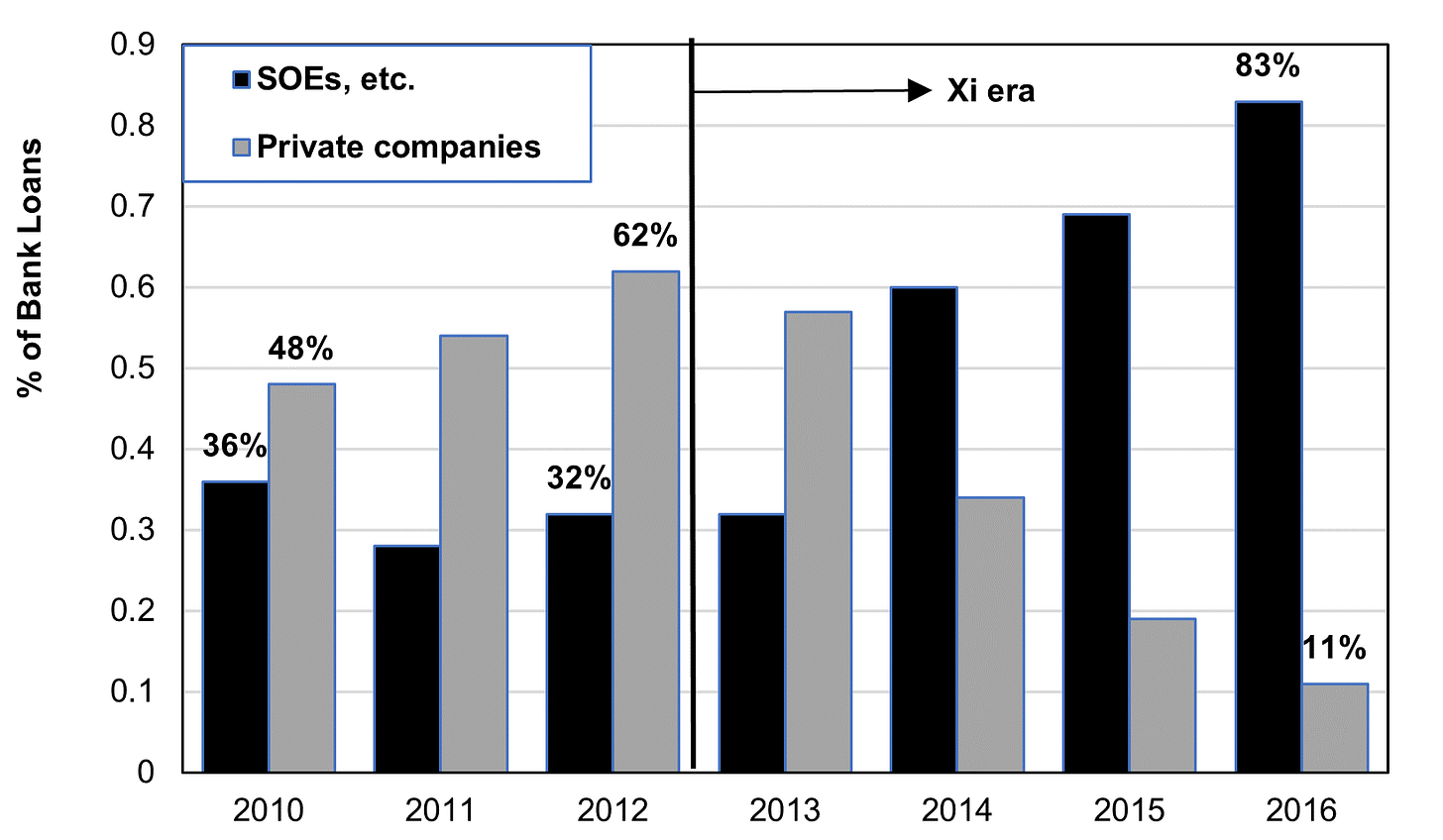

Source: The State Strikes Back, Figure 4.1

Note: SOEs means State-owned enterprises; “Etc.” refers to entities like the local government financing vehicles that fund much of property development

A famous cartoon in a Soviet magazine (published after Stalin’s demise) showed two cranes lifting one gigantic nail weighing tons, with the factory manager saying, “This month’s plan fulfilled.” It seems that, when the central planners told factories to produce X tons of nails, they only made big ones; when they were told to produce X number of nails, only tiny ones emerged.

Somewhere in secret in Xi Jinping’s China, there may circulate a similar cartoon. In the hopes of stimulating more innovation, Xi’s immediate predecessors (President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao) decided to give big subsidies like tax cuts to companies creating lots of patents. So, the companies directed their technologists to work on too many low-quality patents, i.e., innovations that made incremental progress within an existing paradigm. They even reassigned Ph.Ds. who were previously working on more fundamental innovations. As a result, China’s patent applications exploded from around 10,000 in 1990 to 1.5 million in 2020, nearly half the world’s total. Some claimed this meant China was becoming the leader in innovation. In reality, according to a 2022 paper by Chinese academics, producing more low-quality patents and fewer high-quality ones made the economy less innovative. They estimated that the program reduced growth in productivity of capital and labor combined by as much as 9%.

Hu and Wen were willing to be guided by evidence and publicly admitted their failure. Xi, on the other hand, has doubled down. He launched a Made in China 2025 program aimed at China seize supremacy in several pivotal technologies and products. Objective assessments of the effort are rare, but one of the first studies indicates that, on the whole, the program has fallen short, as measured by the creation of high-quality patents and the productivity of companies receiving subsidies. While no one doubts that China has made tremendous strides in technology, including those that directly or indirectly support its military ambitions—as did the USSR in its day—these achievements are hardly enough to match Xi’s ambitions or free it from dependence on the technologies created by others.

Xi’s counterproductive approach is not limited to scientific and engineering innovation. Throwing away the lessons that Deng Xiaoping learned from Japan, he is reviving the economic weight of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), even though they are far less productive than private companies (i.e. less output per input). He is sending Communist apparatchiks into private companies—with executives forced to listen to them on business strategy—even though that degrades performance. And his actions have affected foreign firms as well (see next posting). All of this lowers China’s growth potential, as I’ll detail below.

Why, then, is Xi doing this? Partly because, as a Communist ideologue, he may simply delude himself that his plans are working. In 2018, the government official in charge of SOEs boasted of their huge sales but, as Nicholas Lardy noted, “failed to mention that the profitability of these firms had declined precipitously” over the previous ten years, resulting in lowered GDP growth. Poor economic performance breaks the social contract between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the people, and risks undermining its rule, as party elders warned Xi recently. It could also impair geopolitical ramifications.

What Xi’s Policies Mean for Growth and Living Standards

As I detailed in a recent post, China’s capital stock of factories, infrastructure, office buildings, equipment, etc. is so unproductive that the country has to devote a uniquely high share of GDP to investment (45%). Other countries can invest less for each 1% of GDP growth. That leaves a smaller share of GDP for personal consumption. If China shifted investment from inefficient companies, like SOEs, to more efficient private firms, the country could achieve the same growth rate while reducing the investment share of GDP by 5 percentage points. That would enable household consumption to rise from 38% of GDP to 43%, a 13% (43/38) higher living standard at any given level of per capita GDP.

So, anything that further hurts the productivity of capital ends up making the tradeoff between growth and living standards even worse. China either has to devote even larger shares of GDP to a given rate of growth rate or else the growth rate falls. Today, China suffers from both problems and, as we’ll see immediately below, Xi’s revival of SOEs keeps worsening the economic situation in pursuit of political goals.

(It should be noted that a milder version of this syndrome is one of the key factors in Japan’s lost decades, but that’s a topic for another post.)

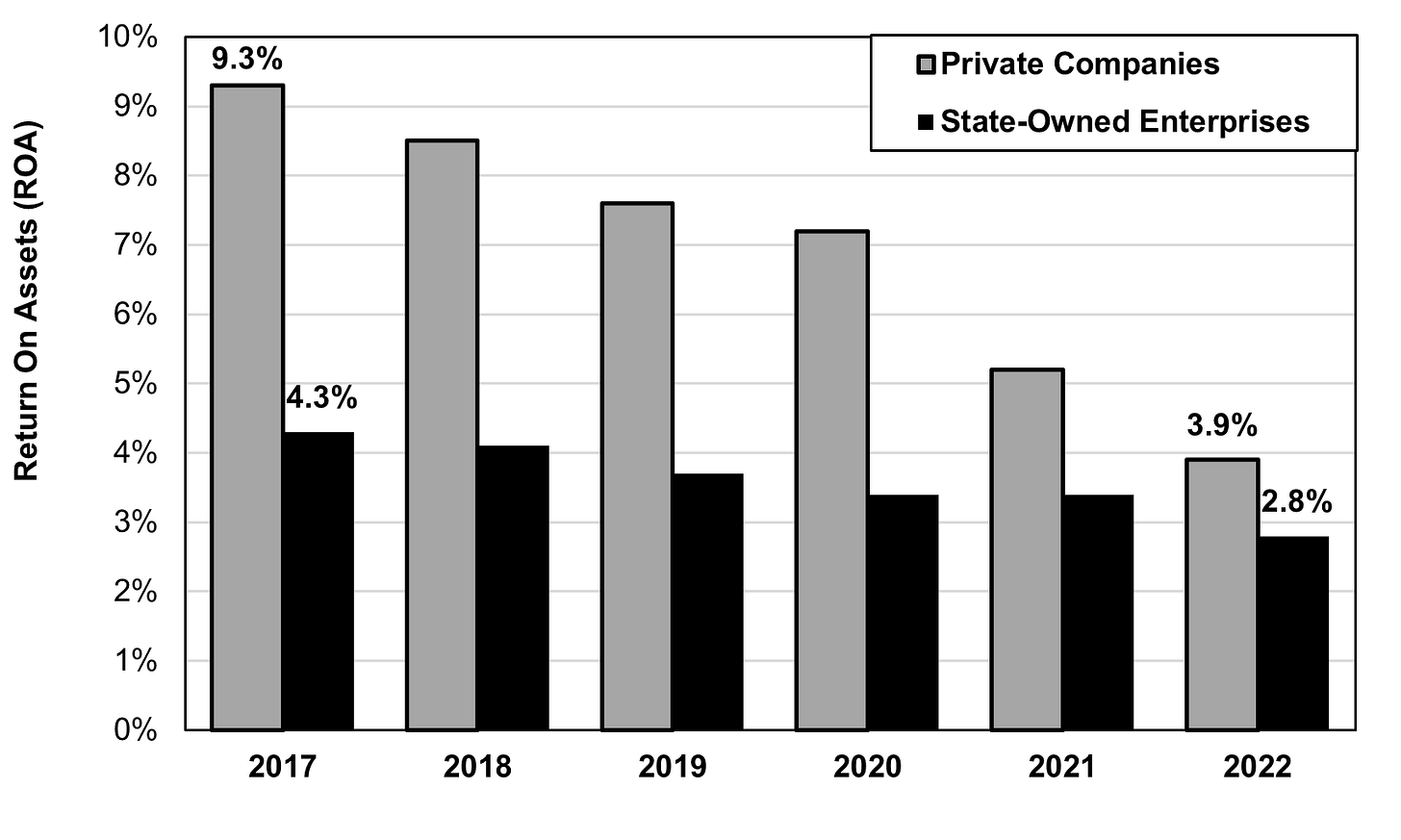

Making China SOEish Again

Under Mao Zedong, all companies were state-owned. Deng and his successors nurtured private companies. But now Xi is reviving the SOEs. The problem is that SOEs provide far less return to the economy for every yuan they invest: in 2017, just a 4.3% Return-On-Assets (ROA) compared to 9.3% at private companies. Worse yet, the SOE’s ROA keeps falling. It was down to 3.2% in 2019, just before Covid, and down further to 2.8% as of 2022. One reason SOE performance is so bad is that efficiency is not one of the criteria used by the government to promote people to top positions. That tells us something about what the CCP cares about.

Unfortunately, China does not publish figures on the share of GDP by type of ownership. So, economists have to estimate. The general conclusion is that, under Xi, progress has been reversed and the SOE share of GDP is now somewhere between 30% and 40%. One important clue is the share of bank loans going to SOEs vs. private companies. Historically, all banking involved state-owned banks and they lent only to SOEs. Gradually, under Deng and his first successors, the share of loans by state-owned banks shrank and SOEs got fewer loans from any sort of bank. By 2012, SOEs and other state business institutions were only getting 32%. Then, Xi came to power. Lending to SOEs zoomed to 83%, while that to private companies shrank to just 11% (see chart at the top).

If SOEs are getting the lion’s share of the loans, then the more productive private companies can’t up their share of China’s investment. Hence, their ability to grow is hampered. In the first half of 2023, private-led investment actually fell 0.2% from the first half of 2022.

For another metric—the market capitalization of SOEs vs. private firms among the 100 largest on the Chinese stock market—see this.

More SOEs Lead to Fewer New Dynamic Private Firms

If all this were not bad enough, Xi’s actions also reduce the efficiency of private firms. Their ROA, while still higher than the ROA at SOEs, is also shrinking (see chart below).

Source: https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/can-chinese-growth-defy-gravity

It’s true that much of the most recent decline was due to the capriciousness of Xi in handling the lockdown and then the abrupt lifting of that lockdown without sufficient vaccinations. And so, ROA could recover somewhat. But such capriciousness is not untypical of dictators.

There are more lasting deleterious changes. For one thing, Xi is demanding that private firms give CCP organizations within the company a say in business decisions and also serve in executive and Board positions. Moreover, the Party is buying “golden shares” of private companies to give it more sway.

The effort began in 2020 when the CCP issued a document called Opinion on Strengthening the United Front Work of the Private Economy in the New Era. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington reported at the time that it looked like the CCP wanted to apply to private companies the same rule it was applying to SOE: “integrating the Party’s leadership into all aspects of corporate governance.” A purge of private entrepreneurs, including giants in high-tech, followed this. How much power will go to the Party instead of the owners remains to be seen.

Even if the Party were not directly interfering with private companies, the mere increase in the role of SOEs is dampening the dynamism of the private companies. A report examining trends from 2003 to 2018 found a decrease in private sector dynamism across a variety of dimensions that are critical to countries in maintaining or improving productivity and growth:

1) The revenue share of firms under ten years of age fell from around 70% of all private company revenue in 2004/5 to around 30% in 2017/8;

2) The 3-year growth rate of young firms relative to old firms fell during this period;

3) The entry rate of new firms has slowed

4) Loans are no longer flowing to the most productive firms as much as in the past.

What makes all this even more worrisome is that the slowdown in dynamism is worse in localities or provinces where SOEs play a larger role in the economy.

Next: Xi alienates foreign firms operating in China.