Xi Jinping Seeks To Ban “Socialism with Japanese and Singaporean characteristics,” Part I

What Deng Xiaoping Learned from Japanese and Singaporean Advisors

Source: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740 and https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288326/china-foreign-invested-companies-share-in-total-import-and-export/

If not for the advice that Deng Xiaoping sought, and received, from Japan and Singapore, there would have been less of the miraculous in China’s economic miracle. Japan showed that China, like Japan, could rapidly develop via export-led industrialization, and that required a partnership between the state and private firms. From Singapore, Beijing learned it needed to bring in foreign companies in order to create modern industries.

These days, in pursuit of political goals at home and abroad, Xi Jinping is weakening many of those successful practices and institutions. Whether Xi is aware of it or not, his posture is undermining economic growth.

Mr. Deng Goes To Tokyo

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, he left China the second poorest among 140 countries for which there is data: just $700 per person per year. (This is measured in constant 2017 dollars that eliminate distortions caused by different price and currency rates movements). Having won a fierce powerful struggle to succeed Mao, Deng Xiaoping called for finally abolishing poverty via “reform” at home and “opening up” to economic interaction with foreign countries.

But how to translate “reform and opening up” into concrete policies? To help figure that out, Deng sought aid from Asia’s previous success stories. Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yee was an inspiration because he showed the Chinese people that they too could create modern industries and wealth. Over the years, 22,000 Chinese officials visited Singapore to learn from its methods. In October 1978, on a trip to Japan to sign a treaty, Deng met with business leaders, toured a Nissan auto plant, and saw China’s future. The confidence gained by the inspiration from Singapore enabled him to tell a press conference in Tokyo, “We are a backward country, and we need to learn from Japan.”

Three months later, China invited one of the chief architects of Japan’s economic miracle, Saburo Okita, to spend several days lecturing more than 500 Chinese officials on how Japan did it, and answering questions from China’s Vice Premier. Okita went on to become one of Beijing’s first official foreign economic advisers. As a scholar explained: “Chinese policymakers felt that Japan offered a successful example of how to combine economic planning with market-oriented reforms. Japan’s experience showed it was possible to use industrial policy to promote basic and export industries...In addition, Japan provided both a justification and a source for the import of foreign technology crucial to modernizing Chinese industry...And if foreign technology was the hardware, then Chinese policymakers viewed Japanese management practices as the requisite software to achieve its full productivity potential.”

Japan showed how a state could use “industrial policy,” a made-in-Japan term, to shift into the most modern industries much faster than Western textbooks said was possible even for a country as poor as Japan was back in 1950, let alone the much poorer China. The World Bank said Japan should stick to textiles, and that it was not ready to move into the latest steel products, let alone cars. Japan proved it wrong. Moreover, Japan showed how to partner state action with market discipline so as to avoid producing a graveyard of white elephants, as other countries had done. China adopted Japan’s term “industrial policy” along with the concept. This included targeting the industries common to industrialized economies; the use of subsidies, channeled finance, and so forth to promote the targeted sectors; introducing foreign technology, and relying on export-led industrialization at a time when Latin America’s strategy of import-substitution was still popular. (For my own take on industrial policy in Japan, see The System That Soured.)

All of this led Deng and his successors to abandon central planning, as well as to promote efficient private firms and reduce the role of Mao’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) hobbling the economy. Deng launched several Special Economic Zones (SEZs) as laboratories for these private firms. Their success enabled him to spread them to the rest of the country, all the while maintaining strict rule by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). “Market Leninism,” two New York Times reporters called it.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s experience led Deng to adopt a practice very much at odds with Japan’s policy of blocking inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and many imports. Japan and Korea did so in the name of national autonomy, but Singapore, and later other Southeast Asian “tigers,” had shown how to use inward FDI to drive rapid development. One of Deng’s first reforms in 1978 was to legalize inward FDI for the first time since 1949, albeit with many conditions. FDI, too, began in the SEZs.

Getting Communists to accept FDI and private companies was not easy. In fact, Deng’s hidebound opponents blamed the “polluting” presence of foreign capitalists for the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. In 1992, to revive reform momentum, Deng undertook the famous “Southern Tour” where he argued—successfully—that China needed foreign companies to access their technology and management methods.

Industrialization Led By Exports and Foreign Companies

For an abjectly poor country, industrialization is the royal route to affluence. But how was China to generate modern industries like steel, electronics, TVs, and electricity, if few Chinese could afford to buy even a simple radio, let alone the electricity or batteries to play it? After all, China’s rural residents had to spend almost 70% of their total income just for food. China couldn’t get rich until it industrialized, but it couldn’t industrialize until its people had enough money to buy factory goods. From Japan came the solution to this Catch-22: let exports provide the market. And so China did. As exports zoomed, so did manufacturing. In 1996, a third of manufacturing output was exported and just before the 2008 financial crisis, the export share rose to 70%, and since then has been around 45%. Moreover, all along, about 80% of the value of these exports consisted of domestic content (see chart below). So, export growth led to growth in domestic manufacturing, which led to growth in living standards of its people.

Source: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIVA_2021_C3

Like Japan earlier, China was able to rapidly upgrade these exports, and thereby upgrade goods on the domestic market, albeit with a lag. In 1985, just 5% of exports were in medium- or high-tech categories. By 2000, the latter had risen to 40% and, by 2020, to almost 60%, of which almost half were in high-tech. In 1987, just a quarter of China's exports consisted of products where global demand was rising rapidly. Just 15 years later, this figure had risen to 60%.

But how could China possibly create products good enough to compete in the global market? China was no Japan, which at the start of its economic miracle was already adept in modern industries, from aircraft carriers to machine tools. Singapore provided that solution: let foreign companies come to China, import the needed parts, and make the finished product on Chinese soil in order to export it. By 2000—just eight short years after the Southern Tour—the cumulative stock of inward investment had soared to 16% of GDP, and foreign multinationals’ share of China’s exports and imports to about half (see chart at the top of blog).

Moreover, as the foreign company share of exports grew, so did China’s total exports as a share of GDP, and as it came down later so did exports as a share of GDP (see chart below).

Source: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators and https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288326/china-foreign-invested-companies-share-in-total-import-and-export/

In fact, the higher the technology content of an export, the more likely it was produced and exported by a foreign company, e.g., 40% for clothing versus 100% for computer products (chart below).

China set conditions on the multinational companies (MNCs) in terms of transferring technology, including by requiring joint ventures with Chinese companies. However, just by producing inside China, the MNCs were training tens of millions of people, even if they had not shown anyone a single blueprint. In China, as elsewhere, foreign companies created tremendous spillover effects that improved the knowledge base, efficiency, and management skills not only of its own staff, but of its suppliers, customers, competitors, and even unrelated companies in a nearby location.

By 2010, according to one estimate, foreign firms generated a fifth of GDP, half of manufacturing output, and nearly half of yearly growth (hard figures are not published by Chinese authorities). Over time, in line with Beijing’s strategy, the MNCs directly a indirectly created a host of high-quality domestic firms, as we’ll see below.

So, here’s the chain of events: a rise in inward FDI led to both more exports and higher-tech exports. That led to two improvements: more income for the Chinese people, enabling them to afford more factory goods, and an upgrade in the kind of goods China produced for the domestic markets.

Private Vs. State-Owned Enterprises

Under Japan’s experience, China learned that private companies, not state-owned ones, are the key to economic dynamism. In the first couple decades after Japan’s 1868 Meiji Restoration, it had created state-owned companies to implement rapid industrialization in some critical areas. The experiment flopped and Tokyo shifted to promoting private entrepreneurs.

China needed to do the same because its SOEs are so inefficient that they hamper national growth, as explained by Nicholas Lardy. Nearly half of the SOEs regularly run losses, i.e., the economy shrinks every time they make something. Their losses are so big—and the earnings of the profit-making SOEs so small—that their losses equal half of the total profits of the profitable SOEs. For every yuan the SOEs invest, even the profitable ones benefit the economy far less than private companies in terms of profits that can finance future growth. In 2015, the Return-on-Assets (ROA) at the SOEs was a tiny 2%, while at private companies it was almost 11% (unlike much other data, ROA by ownership type is available). And yet, as seen in the chart further down, SOEs take up more than a third of the country’s entire outsized investment. That’s one reason that, as detailed in my last post, China has to devote an unusually high share of GDP to investment just to get the same rate of growth.

The good news is that Deng and his successors—until Xi Jinping—had steadily reduced the weight of SOEs in the economy. In 1985, the private company share of industrial output was just 2%. By 1997, just five years after the Southern Tour, that share had risen to an estimated 18%, even though their legal status would remain murky until 1999. In 1998, Beijing also made it legal for private firms to engage in foreign trade. All this occurred as China was seeking accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

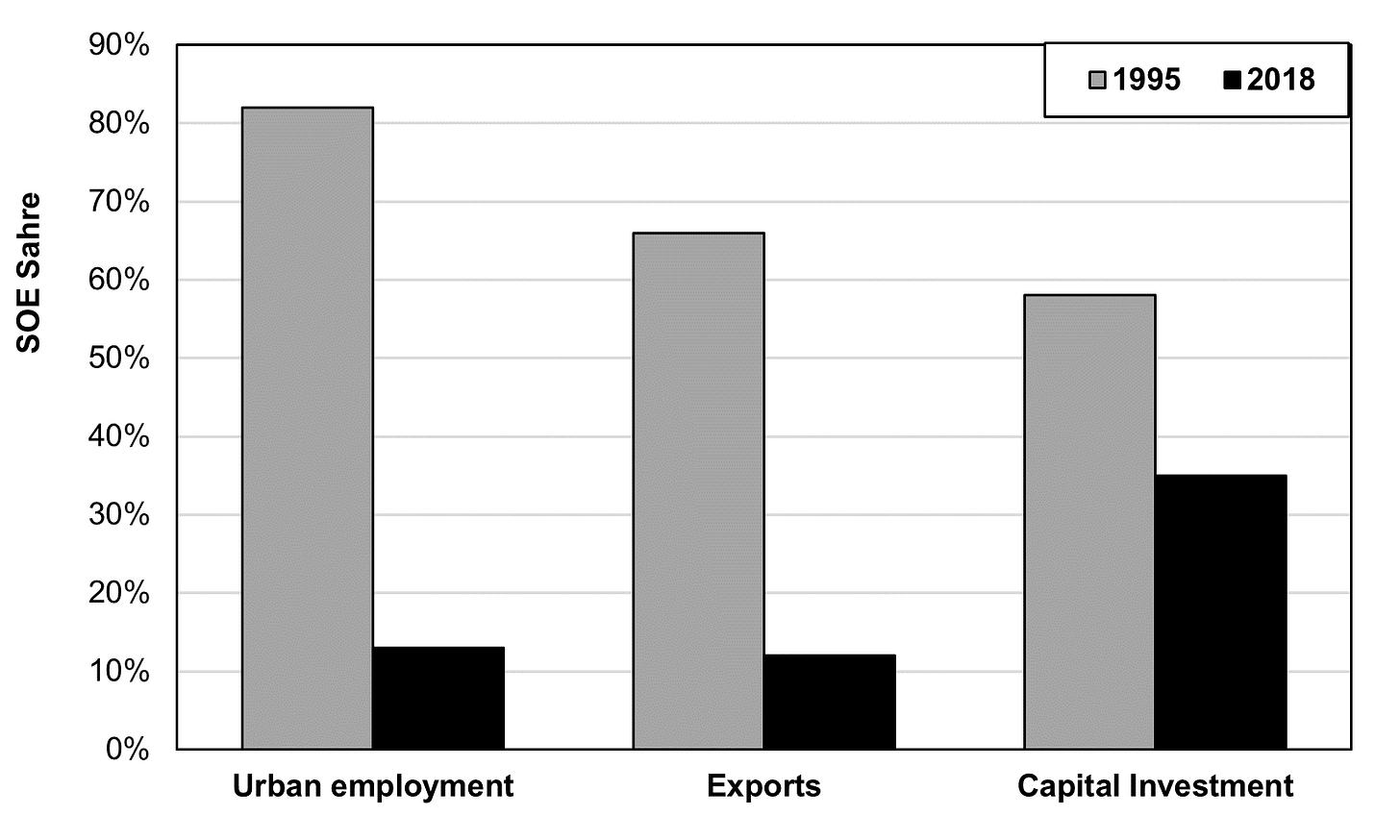

Meanwhile, in the 1990s, Deng’s successor, CCP leader Jiang Zemin, and Prime Minister Zhu Rongji, hugely reduced the SOEs’ numbers, number of employees, exports, and share of capital investment (see chart below). By 2019, the SOE share of industrial assets was down to 40%.

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/25194/private-sector-contribution-to-economy-in-china/

Note: SOE share includes firms owned by the central government and local governments

Since the turn of the century, the vanguard of exports has been switching from MNCs to domestic private firms. Among new high-tech exports, SOEs have played a trivial role going back to at least 2011. Meanwhile, the share exported by private domestic companies has soared from just 15% in 2011 to a peak of 43% in 2019. By contrast, the share exported by foreign multinationals has plunged from 70% in 2011 to just 23% in 2019. In overall exports, the share exported by multinationals has tumbled from a record 58% in 2005 to just 34% in 2021, replaced almost entirely by private domestic firms, like the electrical vehicle (EV) exporters (see again chart above).

The bad news is that Xi Jinping is backtracking on FDI and private companies at the expense of the economy. That’s the topic of the next post

.

Rick, one back story: ca 1978-9 China was actively seeking eurodollar syndicate loans based on oil exports, which would have put it on the path to be the next Nigeria — and we all know how that has gone.

But the oil turned out to be inaccessible. So they began pushing exports of crafts and anything else they could find, including Hong Kong textile producers who moved simple production steps into small villages such as Shenzhen.

Early growth though was driven by a rise in grain production stimulated by big price increases and ironically the fruits of central planning that was finally able to deliver pumps and cement and fertilizer, allowing the Yangtze delta in particular to improve water control and the fertilizer that allowed high yield rice cultivars and more double cropping. Better dikes reduced flooding to minimal levels from an average of 25% crop levels which alone gave an effective 33% increase in yields. That allowed villages to grow more cash crops yet deliver more rice to the government. And with the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 farmers were able to market their produce.

But what was there to spend money on?? New houses!! You can still see brick kilns from that era across rural China. There was also a boom in rural transport and trading enterprises. SEZs came later, but were very local in their impact. Modern industry came later, and arose partly by accident, I can give you lots of details. Deng for example worked for Renault when he was a student in Paris, Shanghai Auto Industry Co was an important source of patronage for the Shanghai cadre who dominated national politics. The VW and later GM joint ventures were an attempt to bolster SAIC against grey market imports.

Construction, though, has remained central to the economy across the last 45 years.