How Did Japan Fall Behind in Creating Personal Wealth?

The Myth of Japan’s Missing Millionaires, Part 2

Source: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000032113364&fileKind=0

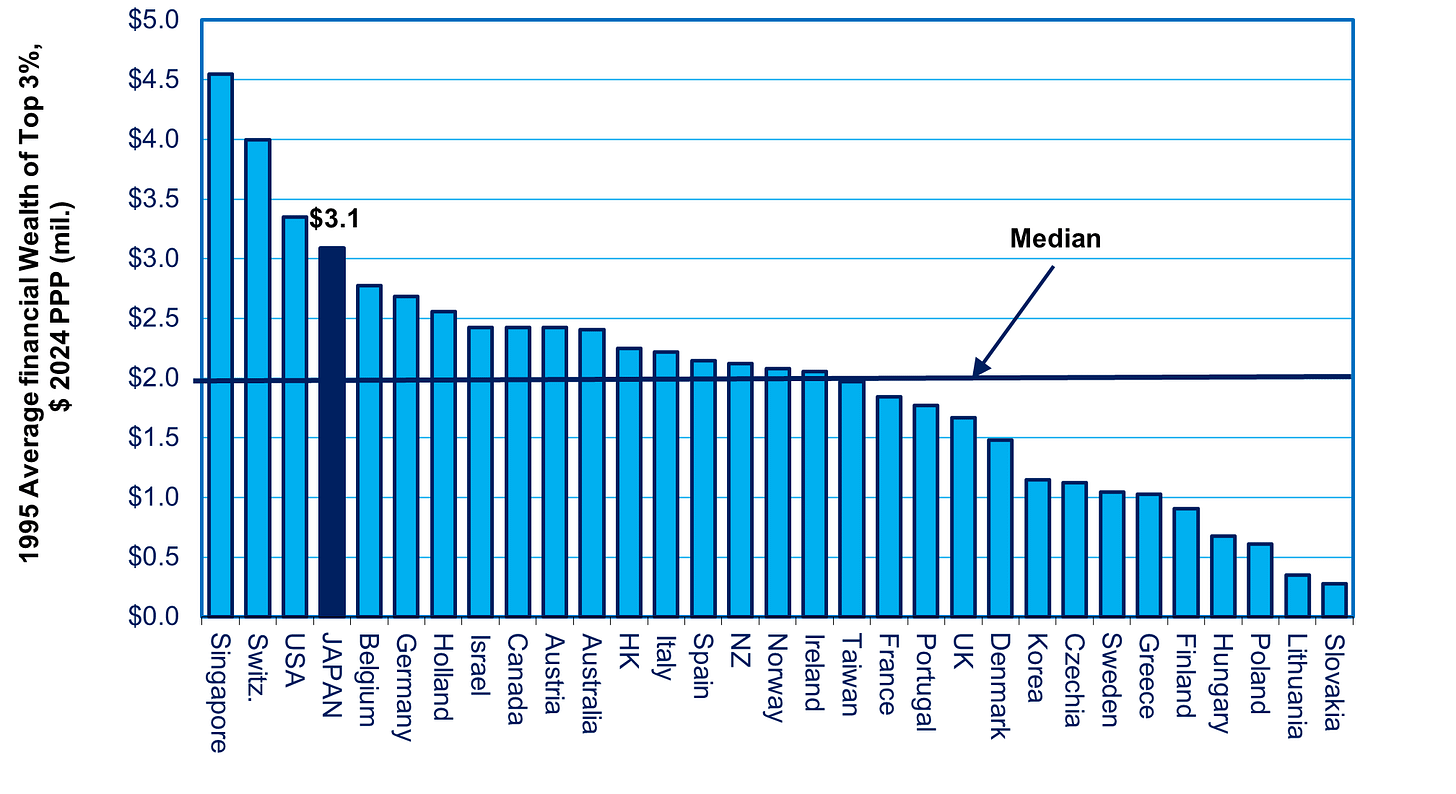

As I detailed in my first post in this series, Japan had proportionally more millionaires than most other OECD countries prior to the lost decades. Japan fell behind because of the drop in asset prices after 1990. In 1995, Japan ranked fourth among 31 countries in the average wealth among the top 3% in each country. But, in 2023, it had fallen to 23rd (see the two charts below) even though the average wealth had grown from $3.1 million to $3.9 million during these years.

Source: https://wid.world/data/ Note: These charts show the average wealth per adult of all those in the top 3% rather than, as in Part 1, the threshold wealth to join the top 3%. The chart uses each country’s 2024 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) dollars, an exchange rate where by X yen or X euros provides an equal living standard to $1 and avoids the distortions caused by currency gyrations. For Japan, PPP is around ¥95/$.

Today’s installment details the reasons Japan fell behind and its prospects for gaining more millionaires as asset prices recover. We care about this because, as I discussed in Part 1, both too few and too many millionaires can hurt growth.

You Want To Be A Millionaire?

Unless you inherit a lot of money, you need a combination of the following circumstances to become a millionaire:

1) A high enough income. If you only earn $60,000 per year, it’s hard to save even $10,000 per year. If you earn $250,000, you can easily save $40,000.

2) Compound interest will build your wealth far more if banks pay 3-4% on deposits instead of 1%.

3) A good chunk of your savings must be invested in somewhat risky, but higher-return assets, such as the stock market or real estate trusts. If I save/invest $20,000 per year and earn 8%, I’ll reach $1 million in 20 years. If I earn only 2%, during the same 20 years, I’ll end up with half of that amount. Moreover, in Japan, income from interest, dividends, and capital gains in stocks and real estate all enjoy a lower tax rate than taxes on wages (except for low-income workers). That raises your after-tax income.

4) Asset prices must be rising on a secular basis. Japan fell behind as stock and property prices languished. As prices rose after 2012, the number of those with at least ¥100 million yen in financial and property wealth rose from 3% of adults in 2012 to 5% by 2023 (see chart in part 1).

I will deal with pre-tax income and taxes in the next part. First come other pieces of this puzzle.

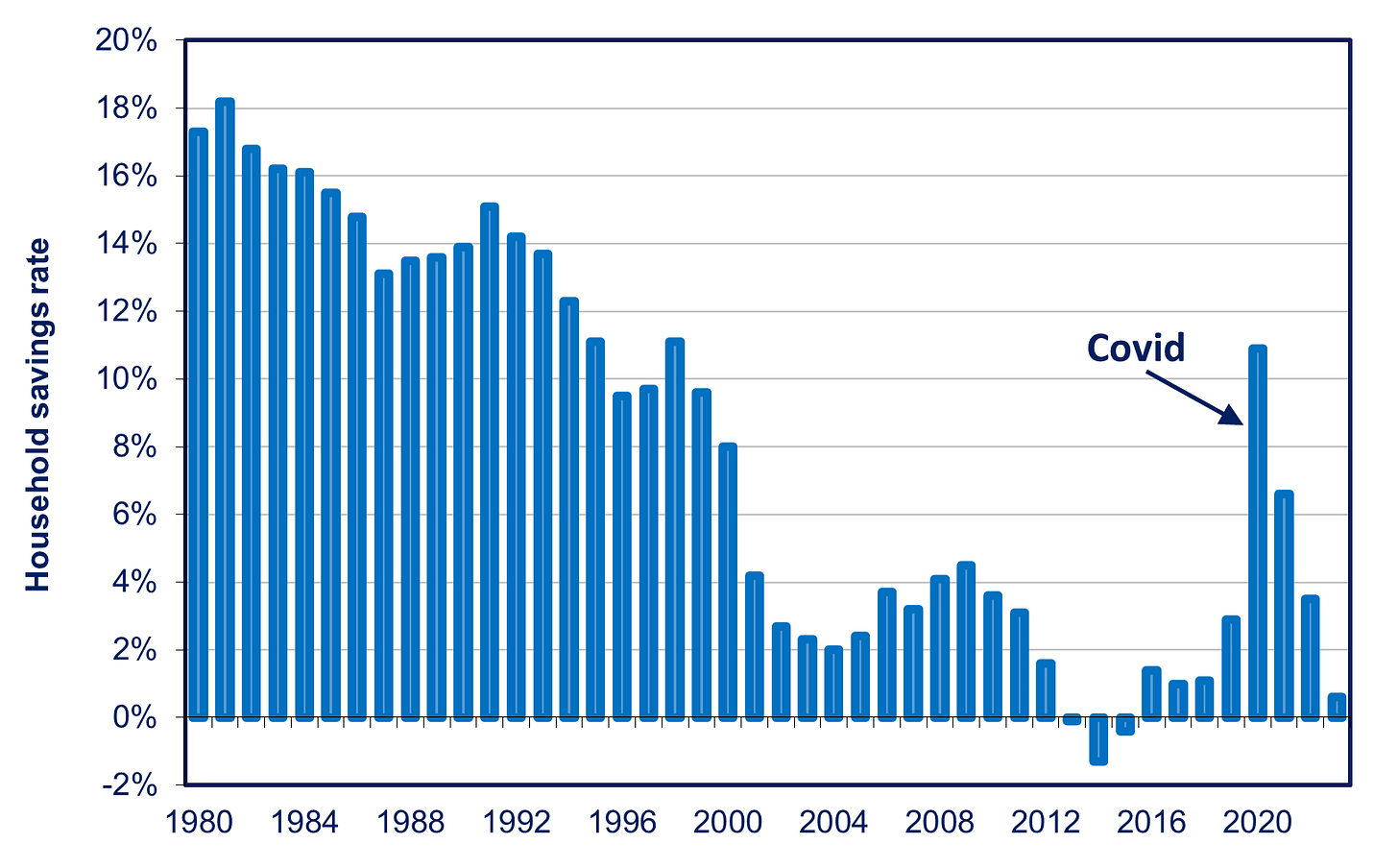

Savings Rate Plunges

Back in the early 1980s, when Japanese households still saved 18% of their income, they were told this was a cultural trait: “Americans like to spend, and we like to save.” The Ministry of Finance (MOF) perpetuated this myth to justify omitting household tax cuts in fiscal stimulus packages, falsely contending that people would just save the extra money.

In reality, as real (price-adjusted) take-home income growth slowed and then flat-lined, people of all ages had to save less—or even draw down their savings in the case of seniors—to fund their consumption. As seen in the chart below, the savings rate steadily fell and then, following the 1997-98 recession, fell off a cliff. In 2023, the savings rate was down to only 0.6%, versus 3.7% in the US (see chart below).

When you are salting away 18% of your income per year, your wealth will mushroom. When you’re saving virtually nothing, your wealth will flatline.

Source: https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/data/kakuhou/files/2023/2023annual_report_e.html and past issues for pre-1994 data

Interest Rate on Bank Deposits Shrivels to Near-Zero

In the mid-1980s, interest rates on bank deposits were around 3-4%. That, along with investments in stocks and real estate, shows why, back in 1995, Japan ranked a surprising fourth out of 31 countries in the average wealth per adult among the richest 3% (see chart below as well as discussion in part 1 of this series).

Then, from 1995 onward, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) attempted to stimulate the economy via near-zero interest rates. From 1996 through this year, the interest rate on all bank deposits averaged less than 0.2%. That means interest on ¥10 million ($105,000 in PPP terms) will bring you just ¥20,000 ($210 PPP) per year. Compounding has been neutered. In the effort to fight deflation and stimulate growth, the BOJ transferred income from household savers to company borrowers.

Middle Class Has Too Little Money In Stocks and Property

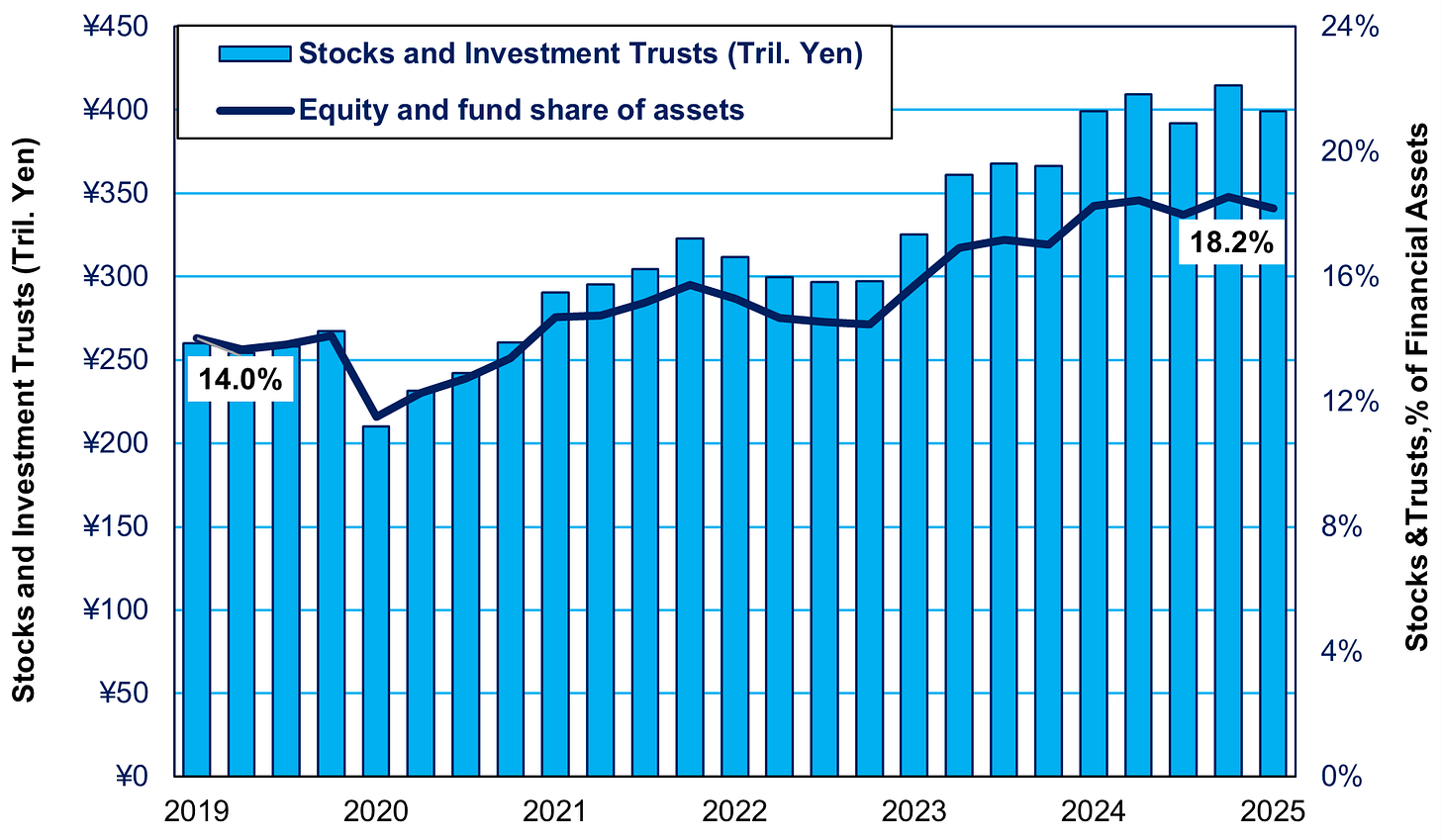

One of the biggest cultural myths about Japan is that risk-aversion makes Japanese avoid risky assets. Instead, they place most of it into bank deposits or insurance annuities that yield a negligible return. The misperception is understandable. After all, we are repeatedly told that only 18% of household financial assets were invested in the stock market in 2023 (see chart below). But that story leaves out real estate.

Source: https://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/ssi/cgi-bin/famecgi2?cgi=$nme_a000_en&lstSelection=FF Note: The rise from 14% in 2019 to 18% today is almost entirely due to the rise in stock prices

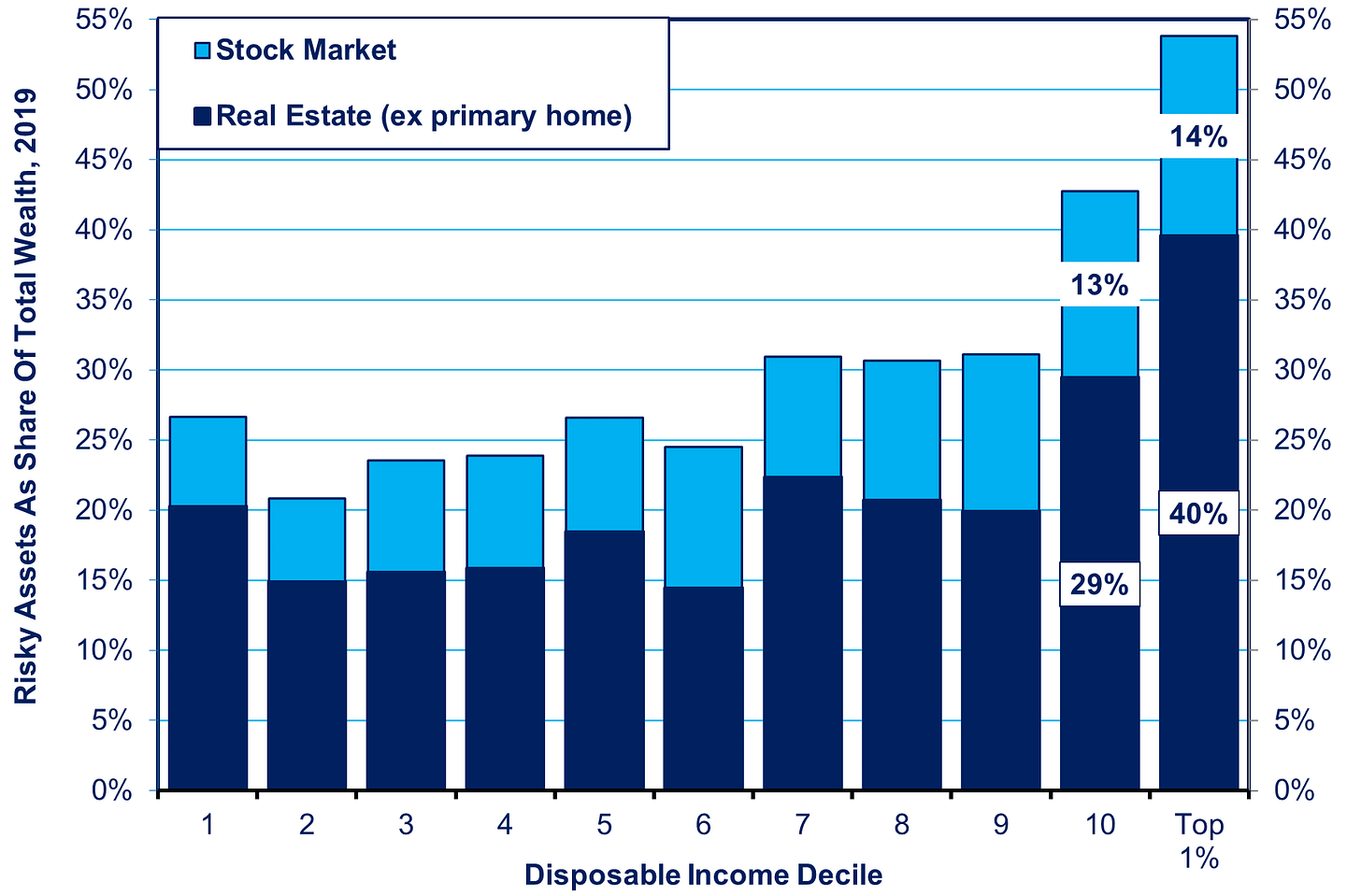

The truth of the matter is that, in 2019 (latest available detailed data), when we look at the assets of the 10% of households with the highest incomes (7.5 million households), we find that 42% was invested in risky assets, i.e., the stock market and real estate (not including their primary home). Among the top 1% income earners (750,000 households), the share in risky assets reached 54%.

On the other hand, for middle-class households—those in the 5th and 6th highest decile—the share in risky assets is just 26% and 24% respectively. That’s because their income is too low to take this considerable risk (see the chart at the top). In 2018, average (not median) disposable income for households with someone working was just ¥5.4 million ($57,000 PPP).

About 60% of all risky assets in Japan is owned by the top 10%, and 24% by the top 1% (see chart below). Notably, their share has not increased over the past three decades, unlike in many other countries, especially the US.

Source: https://wid.world/data/

Japan is not unusual among nations in terms of the share of assets they put into bank deposits. Japan’s top 1% put 33% in such deposits, whereas the EU’s richest 1% average about 34%. It is the US (along with Sweden and Denmark) that is an outlier at around 14%. Japanese in the middle class put about 54% into bank deposits because, as noted above, they can’t afford to take the risk.

What does make Japan unusual is that, among the risky assets, so much is put into real estate (this does not include the primary home): 70% into real estate and 30% into stocks. In 2023, even for the top 1%, real estate accounted for 74% of the risky assets. By contrast, in most countries, real estate comprises just 15% of assets.

This investment pattern might seem unfortunate in terms of wealth-building because over the last decade, stock prices have recovered from lost decade lows much more than property. Compared to 2010, the First Section (aka Prime) of the TOPIX is 3.5 times as high. By contrast, commercial property has just doubled, and residential property is up only 50%.

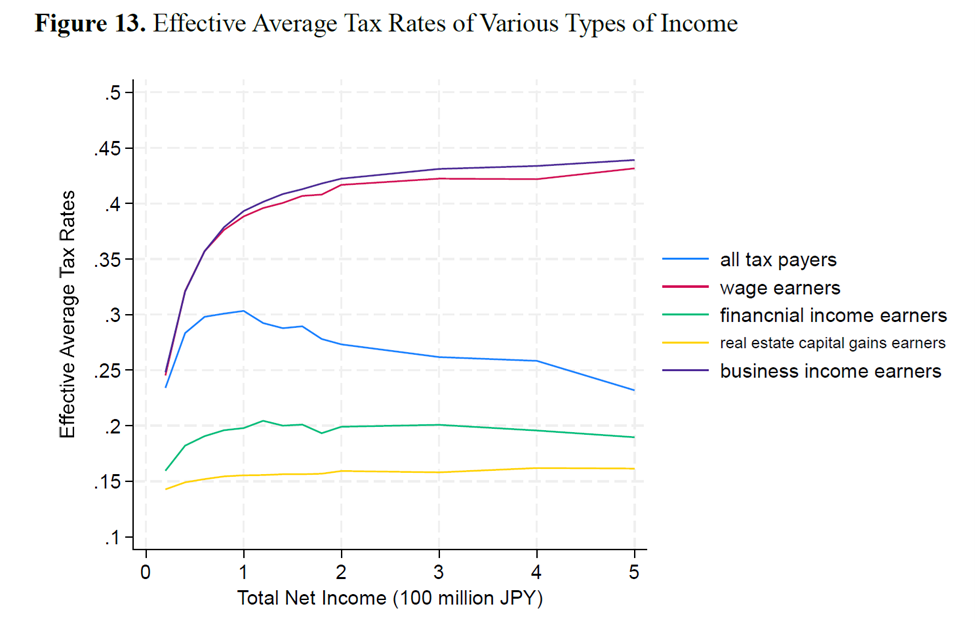

Why, then, do Japanese invest so much in real estate? Many leap to the conclusion that this is due to excessive risk-aversion. This easy answer ignores the tax code.

Property owners not only enjoy capital gains but also a regular flow of income. In 2025, investors could get a return of 3-5% on condominiums, 8% for single-family apartments, and 5-7% on prime property in Tokyo. That’s higher than the dividend yield on stocks. Moreover, at all levels of income, property owners pay the lowest effective tax rate, about 15-17%, whereas those investing in stocks pay a flat 20% tax. Business owners pay even more. Those who get most of their money from wages and salaries pay the highest rate (see the chart below.

Source: https://www.nta.go.jp/about/organization/ntc/kyodokenkyu/kohyo/pdf/250100-01ST.pdf

Investors can lower their taxes even more by writing off expenses. For example, a wealthy person with an annual income of ¥20 million who posts ¥3 million in depreciation annually through real estate investment can save approximately ¥1.5 million in income and inhabitant tax.

Then there are inheritance taxes. Even among the richest Japanese, most property (aside from one’s home) is owned by Japan’s seniors, especially those over 75 years old. They are thinking of bequests, and real estate yields enormous benefits in terms of estate taxes. If someone bequeaths cash or stocks, they are valued at full market value when it comes to estate taxes. However, one can write down the value of real estate by 30% (sometimes more). Hence, it is not unusual for the elderly rich to withdraw money from the bank and sell stocks in order to put money into real estate.

All this may make the risk-adjusted post-tax return for Japanese investors in property close to what they might earn in a stock market recovery.

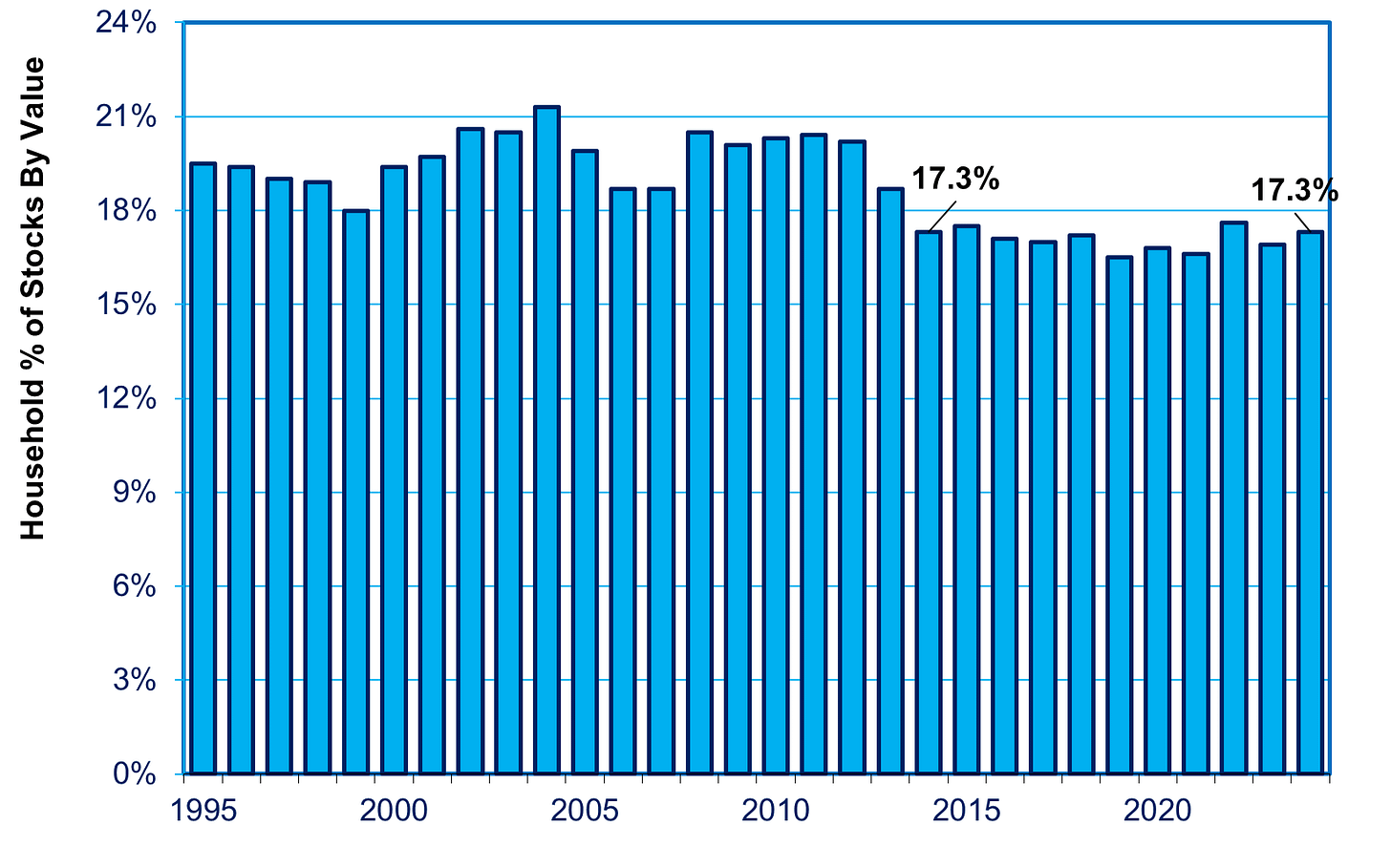

What About the NISA Accounts In the Stock Market?

All over the press and financial services companies, we are being told stories about how the new January 2024 version of the tax-free NISA accounts is creating a boom in investment. There are stories of young people moving into the market. We heard this before, when the first generation of NISA accounts came out in 2014, and it remains to be seen whether this will prove different. In the new version, individuals can invest up to ¥3.6 million per year ($38,000 PPP) up to a lifetime limit of ¥18 million ($190,000 PPP). All of that can be held indefinitely and will be permanently exempt from the normal 20% national and local tax on dividends and capital gains.

It could make a big difference over time, and that would be good for Japan’s middle class, but it’s too early to tell. So far, a lot of people are opening NISA accounts. However, the data show that most of them are simply transferring money to this tax-free vehicle from stocks and investment funds that they already own. If households were really moving new money into the market, then the share of the total market owned by households would have risen. But it has not, at least not so far. That share was 17.3% in 2024, the same as in 2014 (see chart below).

Interestingly, the most popular NISA investment trusts are those that seek higher returns in the US and other overseas countries.

Conclusion

If someone is already well off, there are ways in Japan to become even more affluent, perhaps even truly wealthy. However, with median wages stagnant, it is hard for most Japanese to take advantage of these opportunities. So, one reason Japan does not have more millionaires is that salaries for skilled workers—doctors, lawyers, PhDs, scientists, engineers, company managers, etc.—offer too small a premium relative to the median wage. This is detailed in the next part.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Very interesting, thanks for writing this. With bank deposit interest rates in Japan so low, and with the Japanese stock market being sluggish until just recently, I wonder why few Japanese invest in foreign stock or bond markets. Are ETFs or mutual funds with foreign stocks not easily available in Japan, or are there worries about currency exchange rates, or something else?

Simply, Japan doesn't quite have actual cashes from commoners to the elites. However, they just simply have a lot of credit for now. The credit advantages come from Japan's abilities of massively borrowing from foreign investors and global funds to finance the militarization of pre-war era and miracle economy of 20th century. Japanese people of those periods were excellent on leveraging those loans to mostly break even and sometimes make a profit. Now, Japan's population decline has reached the point of no return but mostly the universal decline of economic competitiveness and leadership qualities that it can no longer leverage international loans to grow anymore. That's why Japan lost the triple A credit rating after the bubble burst, and everything just goes down from there.