Source: https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/data/kakuhou/files/2021/tables/2021i5_en.xlsx

Note: Nominal data deflated by Consumer Price Index for constant 2015 measure

If you own a factory and cut workers’ wages by 5%, you can increase your profits. If, however, every employer cuts wages, as Japan’s employers have been doing, then consumers can no longer afford to buy these employers’ products. The result is recession. To avoid that, someone has to step in to substitute for the missing consumer demand. In Japan, that “someone” has been the government in the form of chronic budget deficits. That is the reason Japan’s efforts to end the deficit have repeatedly failed. Japan cannot keep its economic head above water without those deficits.

The Hits To Household Income

Real (price-adjusted) wages and benefits per worker peaked at ¥4.27 million in 1996 and today, a quarter century later, they are down 3% to just ¥4.14 million (see chart below).

Interest on savings—which is particularly important to seniors—plunged as a result of the Bank of Japan’s cuts to interest rates (see chart)

Moreover, the doubling of the consumption tax in two steps (2014 and 2019) left households with less disposable (after-tax) income, i.e., income available to spend.

Given these and other hits to income, no wonder total real personal consumption is down 3% from ten years ago

.Source: https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/data/data_list/sokuhou/files/2023/qe233/tables/gaku-jk2331.csv

You might ask whether the real reason for decreased consumer spending is that consumers are just choosing to spend less and save more, as is sometimes claimed by the Ministry of Finance (MOF). In fact, the opposite is true. The fabled high savings rate of Japanese households is long gone. Instead, people are sustaining consumption as best as they can by spending larger and larger portions of their stagnating income. The household savings rate fell from 16-18% of disposable income in the early 1980s, to around 10% in the 1990s, and 2-4% by the 2000s. In a couple of years, they drew down their savings as they spent even more than their disposable income (see chart below). The lockdowns of the Covid years are an exception. Not lack of will, but thinner wallets, explain the drop in consumption.

.So, How Did GDP Grow?

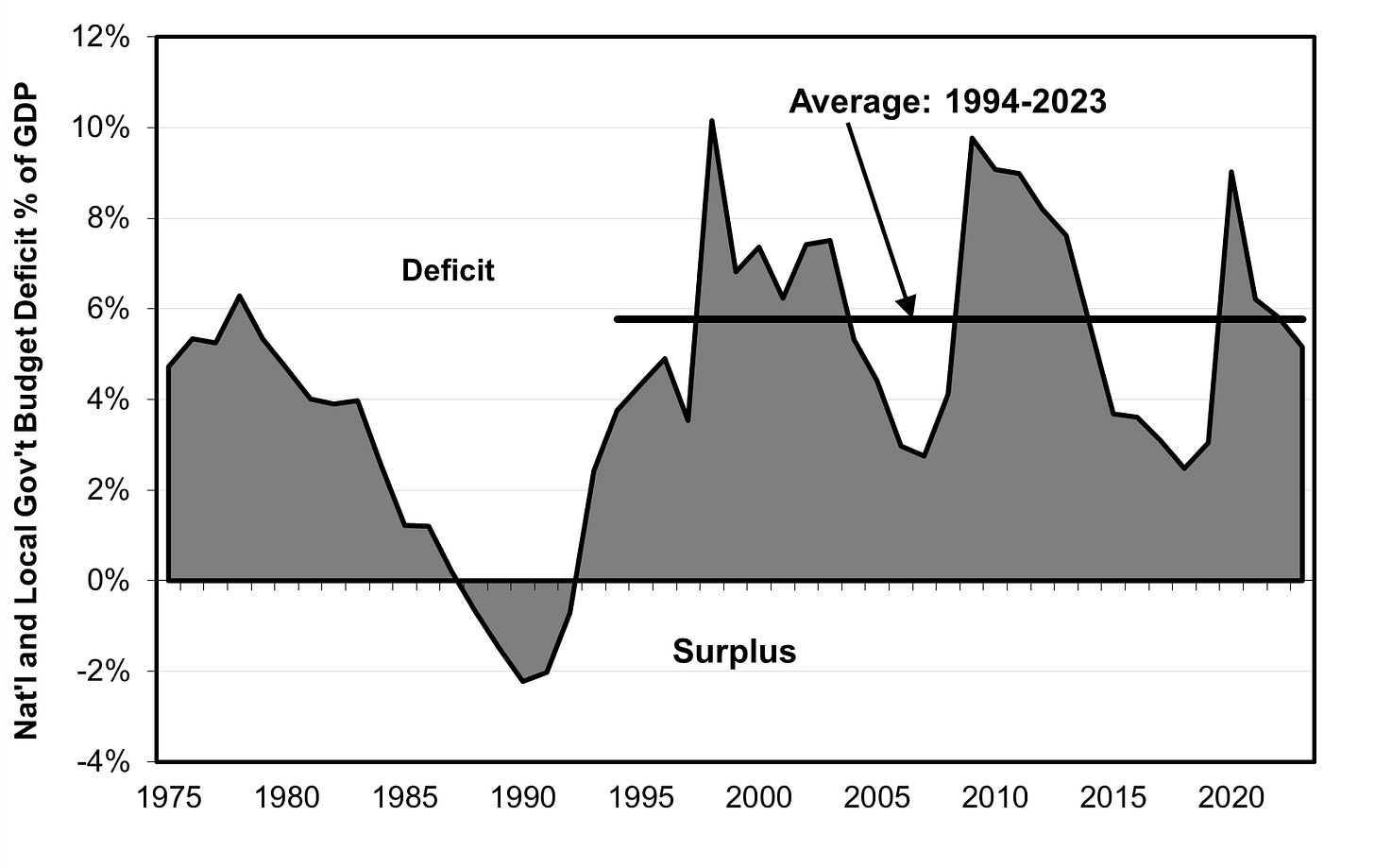

Since consumption accounts for a bit more than half of GDP, how, then, did GDP manage to grow 5% during the last decade despite the fall in consumer spending (see again chart above)? The answer is that, for the past quarter of a century, Japan has run a budget deficit averaging almost 6% of GDP per year (see chart below). Every time Tokyo lowers the deficit, a weak economy forces it to raise the deficit again.

.Source: OECD Outlook Statistical Annex at https://www.oecd.org/economy/outlook/statistical-annex/

Note: This is the total budget balance of national, prefectural, and local governments. The one period of surplus during the past half-century was during the late 1980s “bubble.”

Deficit-Financed Consumer Income and Spending

People are most familiar with the government raising the deficit by spending more on goods and services, such as public works, government employee salaries, supplies, education, and healthcare. In a previous post, we saw that, from 2018 to 2023, GDP was flat while government spending rose 8%.

A less well-known method is to transfer money directly to consumers—mainly via social security for the aged and the abject poor—which the latter can then spend. So, an increasing amount of what looks in the GDP tables like private demand, i.e., personal consumer spending, is actually financed by government deficits. Without that transfer of money, consumer spending would have fallen even more, thereby causing overall GDP to slump.

To see the critical role of government cash to consumers, see the chart at the top of this blog. The part in black is “primary income” per capita. Except for wages for government workers, almost all of the primary income comes from the private sector in the form of wages, self-employed income, rent, interest on savings, insurance annuities, dividends, etc. Real primary income per capita dropped 4% from its 1995 peak to 2021. During the same period, government transfer payments—the grey part of the top chart—exploded by 50%. Almost all of this can be spent since most social security benefits are exempt from income taxes. Consequently, as a share of disposable (after-tax) income, these government transfers rose from 17% in the 1990s to 27% as of 2021 (see chart below)

While the government did raise consumption taxes to help pay for these transfers, it did not do so enough to cover the cost. Had it done so, real disposable income would have plunged. Ultimately, disposable income per capita fell just a tiny bit from 1995 through 2021 (see chart below)

.As noted earlier, most of these government cash payments go to the elderly. Still, social security has not been spared budget cuts. Social security per senior has fallen, and that, too, is taking its toll on consumer spending (see chart)

The net result is that much of consumer spending is now financed by never-ending government budget deficits. Whether through government spending or these transfer payments, Japan is a deficit addict.

METI’s Fantasy of Tax Cuts Boosting Corporate Investment

The Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) has long touted the fantasy that it could boost growth and solve the deficit problem by cutting corporate taxes. This, METI contended, would induce companies to invest and perhaps even raise wages.

METI’s mirage never became reality. During 2010-23, Japanese companies didn’t expand their capacity at all, according to the OECD. Secondly, companies raised their profits by cutting wages. All METI accomplished was to raise the budget deficit even more while transferring money from households to companies.

As a result, Japan’s two million corporations regularly rake in cash that they don’t plow back into the economy. Their annual cash flow surpasses what they spend on investment by 5-6% of GDP. That’s just about the same amount as the average annual budget deficit in recent years. If Japan wants to cut the budget deficit, it should revoke these useless gifts to the corporations.

Bottom Line

The deficit is not the cause of Japan’s problems, but a symptom. Yes, the chronic deficit does exacerbate Japan’s problems. But trying to cure Japan’s problems by slashing the deficit is like trying to cure a fever by breaking the thermometer.

Available at Amazon and other booksellers in both hard copy and e-reader formats

As a Korean, I envy that there are foreigners who give sincere advice on the Japanese economy. In Korea, there is none (or maybe I don't know)

As usual, thanks for providing clarity backed up by facts and figures. Will the long-term trajectory of demographic trends help or hinder (assuming no material changes to policy)?