Japan and Climate Change: Not As Bad As It Looks, Part I

Economic Forces Blunting Efforts of Fossil Lobby

Source: https://carbontracker.org/reports/put-a-price-on-it/ Note: Estimate for Japan

It’s easy to feel frustrated about Japan regarding climate change. It often feels as if the country only makes progress kicking and screaming, that the fossil fuel lobby has a stranglehold on policy, that its automakers are behind the curve regarding electric vehicles (EV), and that Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is reversing the progress made under his predecessor, Yoshihide Suga.

This perception is strengthened by Japan’s moves at the 2023 Group of Seven (G7) meeting of cabinet ministers in charge of energy and climate. Tokyo (with the support of the US and the EU ) blocked a British proposal to accelerate to 2030 the 2035 deadline for the complete phaseout of “unabated” coal. The latter is coal without carbon capture technology (CCS). While CCS may be necessary for certain industrial sectors, it is not cost-competitive for electricity generation and will likely never be, given the fall in renewable energy (RE) costs. The International Energy Agency has said that achieving net zero by 2050 requires rich countries to phase out unabated coal by 2030. Rather than offer a later deadline, Tokyo successfully eliminated any deadline, using the Ukraine war as the pretext. Tokyo also extracted a formulation accepting new gas-burning power plants if they could be claimed to lower emissions, e.g., by replacing coal. Japan’s machinery makers want to keep exporting such plants to developing economies.

All this, however, is just one side of the picture. Japan is a battleground. Yes, the fossil lobby in and out of government tries, not to stop, but to slow down, the shift from fossil fuels to RE. On the other side, hundreds of leading companies, and parts of the LDP, want to reduce emissions more quickly and some finally accept the use of carbon taxes.

Recall that Suga, defying the fossil lobby, upgraded Japan’s 2030 emissions reduction and RE goals. He also adopted the goal of reaching net zero by 2050; up from sometime between 2050 and 2100 (see table below). While the 2030 goals may not be met, more will be done than if Suga had not acted.

Source: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/6th_outline.pdf

The Economic Game-Changer

What’s most important is that behind the “move more quickly” faction stand the forces of economics. Within a few years, Japan will find building and running new solar and onshore wind facilities cheaper than operating existing coal and gas-fired power plants. By 2020, that was already the case in countries with half the world’s population. In 2030 in Japan, it will cost an estimated $108 per Megawatt-hour (MWH) to run existing coal plants and $112 for gas (see chart at the top). But to build a new wind or solar farm including battery storage for electricity—because the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow—the cost will be just $83 for solar and, by 2032, just $100 for onshore wind. Should Japan impose a carbon tax of even $30 or $60 per ton, the price crossover point will come earlier.

When doing the right thing for the environment becomes the more profitable thing for producers and the cheaper thing for customers, that’s a powerful game-changer. That is why, in 2023, for every dollar of new investment in coal, oil, and gas around the globe, 1.7 dollars are being invested in clean energy. The latter includes renewables, electric vehicles, nuclear power, grids, storage, low-emissions fuels, efficiency improvements, and heat pumps.

These market forces are finally compelling Japan’s automakers to shift to battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs) faster than they intended. The shift was sparked by a loss of sales overseas that is putting China on track to overtake Japan as the world’s biggest auto exporter. In the last couple months, Toyota announced its goal of producing 3.5 million battery EVs (BEVs) by 2030, up from 2 million just a little while ago. The new goal equals 35% of current global sales. Honda now targets 2 million BEVs by 2030, equal to half of current sales. In the past, Honda’s BEVs goals were fuzzier due to an emphasis on “electrified” cars, which includes both traditional hybrids and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs). Nissan’s goals are still fuzzy: 55% electrified cars by 2030, up from 50%.

On the downside, these automakers are still hedging their bets by investing billions of dollars on cars that are either losing popularity, such as traditional hybrids, or failing to ever gain it, like PHEVs and the truly futile fuel cell vehicle. In 2022, global sales of BEVs and PHEVs combined overtook sales of traditional hybrids: 10.5 million to 8.4 million. BEVs outsold PHEVs three to one. Moreover, Bloomberg reported that 2017 “will end up being the all-time high” for global sales of gasoline-powered cars.

Meanwhile, dozens of planned coal plants were never built, not due to political pressure, but because they no longer make financial sense. Global Energy Monitor reported in 2023, just one small plant “stands between Japan and a claim of ‘no new coal’ in the country. This is in contrast to the nearly 10 GW [Gigawatts] that was in the works just two years prior.”

Solar power has expanded at a much faster-than-expected pace due in large part to government subsidies. The share of RE electricity generation nearly doubled from 12% in 2015 to 22% in 2022. As a result, annual power sector emissions in 2022 were 16% below 2015 levels. The role of subsidies belies any notion that Tokyo opposes RE. Rather, for reasons we’ll explore in Part II, it wants a combination of RE and fossil fuels.

At the same time, a growing number of leading corporations in sectors like electronics are urging the government to move faster on RE because, otherwise, they won’t be able to sell to big overseas customers committed to 100% clean energy during the 2030s or sooner. A couple hundred of them now accept the need for a serious carbon pricing system (details in a later installment).

All of this is encouraging. Due to the economic shift, the forces for progress on climate change are gaining strength, even in Japan. Momentum is on their side. The bad news is that progress is still far too slow to avoid a climate catastrophe. No Group of Seven country is on track to reach net zero by 2050, but Japan is the furthest from the goal.

More policy action is required. But policy action comes more easily when it is backed by economic incentives for producers and consumers alike.

Growth, Energy, and Emissions

The history of energy has been progress toward fuels that are more efficient, that can do things that earlier forms of energy could not (e.g., electricity), and that are less smoky and sooty. All of this adds up to downward pressure on carbon emissions, even though only recently has that become a conscious goal.

The firewood and dung still used by three billion people emit many times more carbon than a gas stove to boil a quart of water. All the cement and steel used to build infrastructure and buildings as countries industrialize are immensely carbon-intensive. By contrast, the services that predominate in rich economies need less energy. At the same time, a modern electric arc steel plant emits far less carbon than previous steel mills.

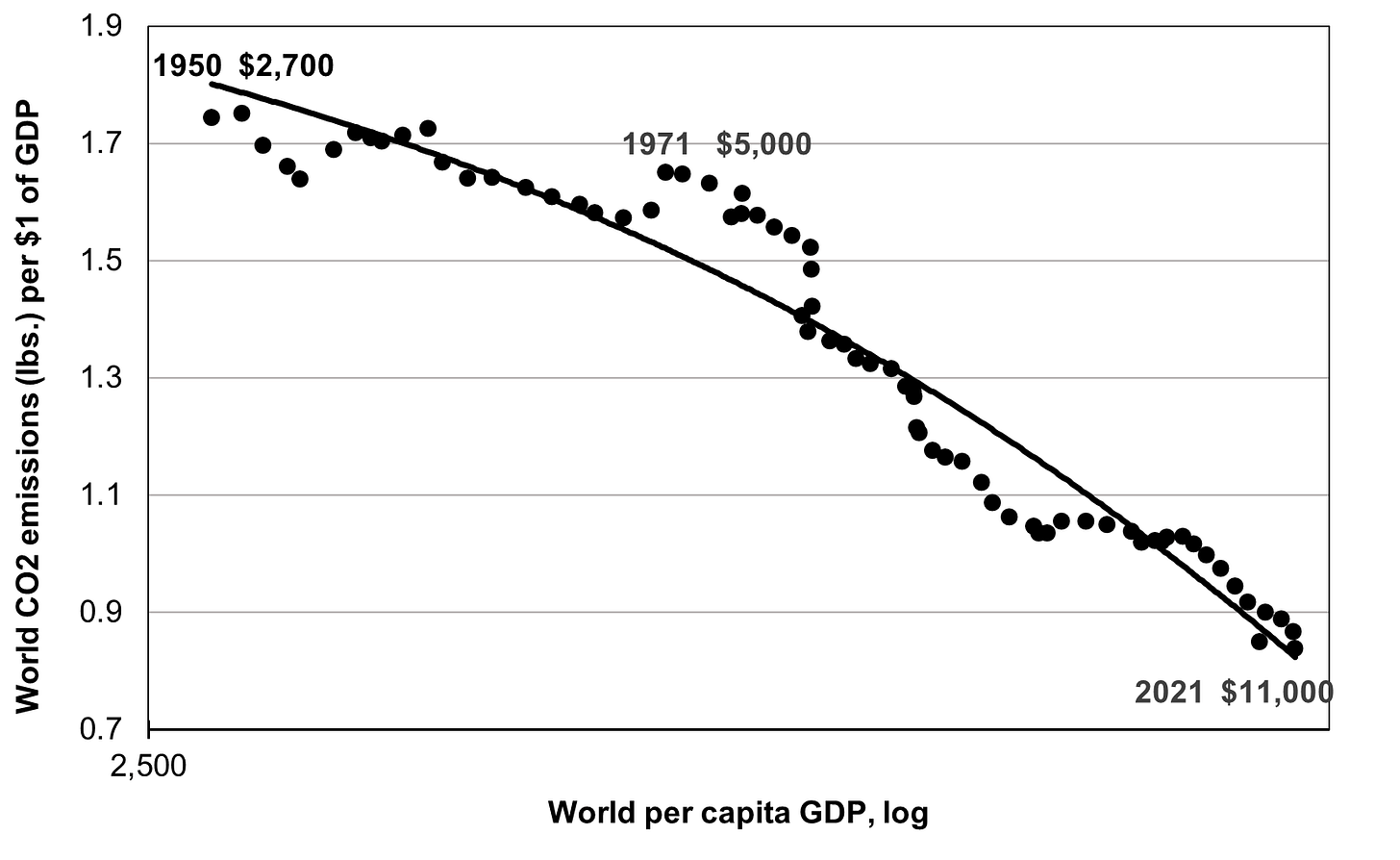

The consequence is that, over the last seven decades, as world per capita GDP quadrupled, the energy needed to produce a dollar’s worth of GDP fell by almost half (see chart below).

Source: https://nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/owid-public/data/co2/owid-co2-data.xlsx

Note: The horizontal axis is on a logarithmic scale so that an equal length along the axis shows equal proportionate growth, e.g., a doubling.

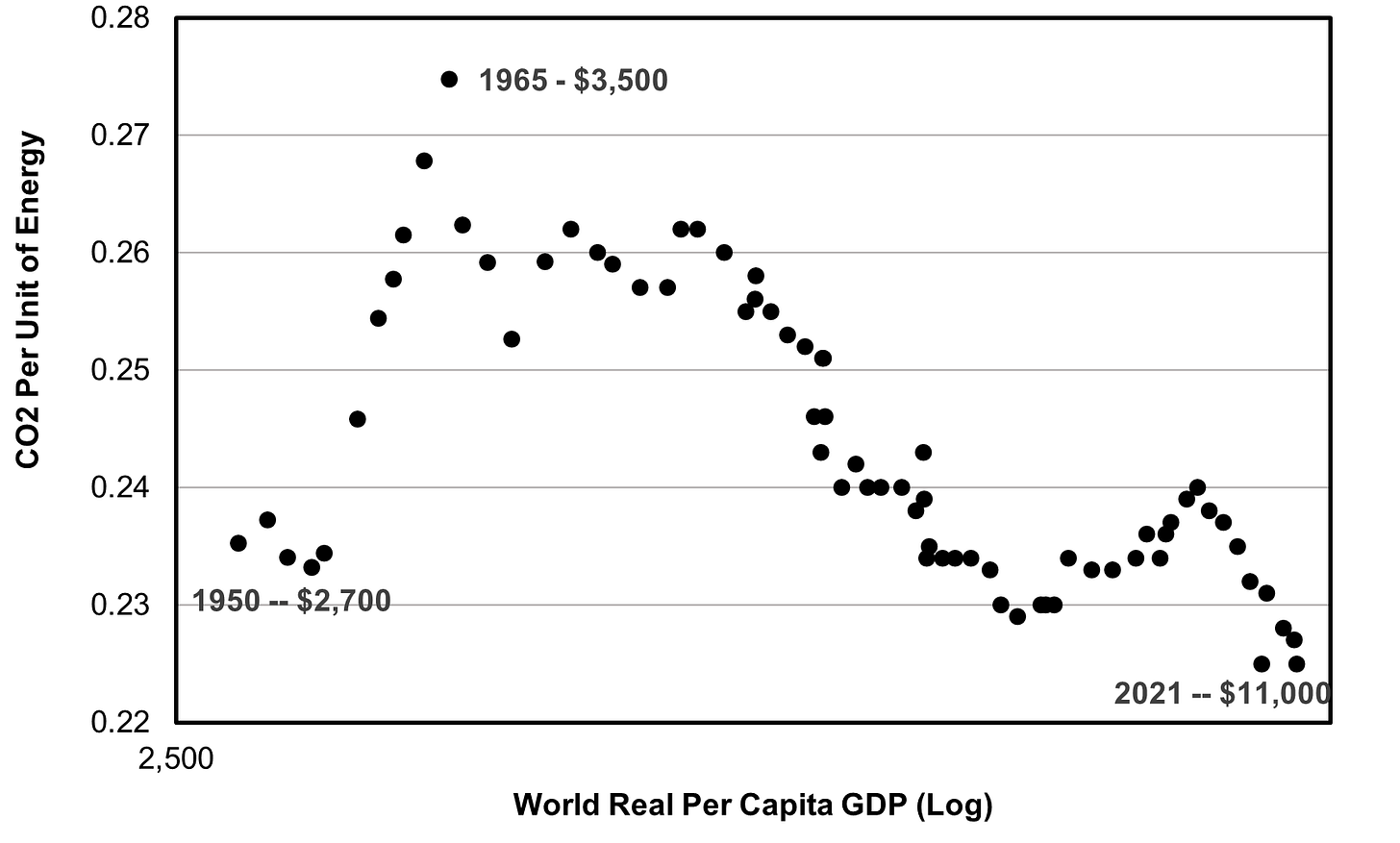

Initially, as relatively poor countries grew a bit richer and farming became more mechanized, they substituted fossil fuels for animal power. Consequently, carbon emissions per unit of energy rose, then peaked in 1965. Then, as these countries grew still richer, they shifted to cleaner forms of energy. Average carbon emissions per unit of energy are lower today than they were back in 1950 (see chart below).

Finally, consider the impact due to the combination of less energy per dollar of GDP and lower emissions per unit of energy. As per capita GDP doubled from 1950 through 1971, emissions per dollar of GDP fell just 6%. But when per capita GDP doubled again from 1971 to 2021, emissions per dollar of GDP halved! (see chart below). Growth is not the enemy of the effort to reduce emissions, but its partner.

Of course, since per capita GDP quadrupled and the population kept rising, total global emissions soared for a long time. Finally, however, in 2012, emissions peaked (see chart below). Now, we come to why they peaked and have begun to decline, even if they do so far too slowly.

The Great Decoupling In Rich Countries

Once some countries got rich enough, there emerged an unprecedented world-historical change, a decoupling. GDP kept growing even as total energy consumption and total emissions fell. As of 2019, 28 countries had already passed their peak emissions, Japan is one of them. After 1975, energy and emissions grew more slowly than GDP, and, beginning in 2005, they started shrinking even as the economy kept growing (see chart). Since 2005, Japan’s GDP grew a measly 5%, while energy use fell 21% and emissions fell 17%. Had the Fukushima nuclear disaster not revived the use of coal, emissions would have fallen more.

There are big differences in the pace of this progress, and that shows the role of politics. In North America after 2007, even though GDP rose 24%, energy use dropped 4% and emissions dropped 17% (see chart below).

In the EU, emissions started falling as early as 1980, and energy a few years later, Even though GDP doubled from 1975 to 2021, energy use fell 10% while emissions fell 30%.

Even China is showing the initial signs of decoupling (see chart below).

Economics and Politics

The upshot is that the natural processes of economic development are already pushing Japan and others in the right direction. While economic forces are not sufficient, the policies needed for net zero by 2050 can count on market forces as an ally, not an obstacle. By contrast, the fossil fuel lobby in Japan, and elsewhere, is increasingly forced to fight a rearguard battle against the market.

Coming Up in Part II: The conflicting motivations shaping Japan’s energy and climate change policy

Well written piece. I do think though Japan needs to think more about how overall environmental impact is included into the progress on global heating. Compared to other developed countries, there still seems to be free reign on destruction of green field sites, forests etc. Until there are changes on building regulations, tax breaks on inheritance taxes, this will continue unabated.

Nice overview and good to highlight some optimism on Japan and climate change.

Looking forward to part two. Interested in your insights on why Japan has notably weak political activism on climate change (where’s the Greens party?)

Interested also in how Japan became an outlier on certain tech trajectories, like “futile” use of hydrogen for autos.

I often hear it argued that Japan’s has a notably poor renewable energy endowment. Not a lot of sun or empty space, and where it’s windy, the sea is often deep (and deep water wind isn’t ready for grid scale deployment).

Is this grounded in facts or just risk aversion and self serving arguments from the fossil fuel lobby?