“Mar-a-Lago Accords” Not Guiding Trump

Internal Contradictions, Sophistry, and “Alternative Facts”

FLASH: Friendly atmospherics prevailed at yesterday’s Japan-US trade talks, but there was no conclusion. Meanwhile, Trump is maintaining both the 25% tariffs on Japan’s automotive exports and the across-the-board 10% overall tariff while both sides await more meetings.

----------------

With Donald Trump making such radical changes in America’s trade policy, people—including Japanese policymakers and business executives I’ve been speaking with—want to believe that there must be a “grand strategy” behind it. In their quest to find out what Trump really wants, they have latched onto a document proposing “Mar-a-Lago Accords,” put out in November 2024 by Stephen Miran, a hedge fund manager whom Trump later made chair of his Council of Economic Advisors.

This conclusion, as Miran readily acknowledges, is a myth. “Anyone thinking what I wrote in November is the policy agenda we’re secretly implementing right now is just looking for something to write about,” he told the Washington Post. Miran blames America’s trade deficit on a structural problem (the dollar’s reserve currency status) but Trump prefers to blame culprits, saying the European Union was created to “screw” America. Miran proposes a multilateral currency agreement, but Trump prefers tariffs and one-on-one begging by countries for relief. I doubt Trump has even read Miran’s paper.

Miran’s paper is partly a high-falutin rationalization of policies chosen for other reasons and partly an attempt to make Trump’s actions look more thought-out than they really are. It’s a mélange of sophistry, internal contradictions, and false assertions, dressed in the garb of seemingly erudite economic terms and doctrines.

More importantly, Trump is a creature of grievance and impulse, not coherent strategy. Trump ardently seeks American technological supremacy. Would a rational strategist then cut off billions in research grants to the universities that produce that technology?

Miran’s Argument

Here, in a nutshell, is Miran’s argument. America’s manufacturing has been hollowed out by a persistently overvalued dollar. The latter makes imports cheaper, leading them to surge and America’s factories to close. This overvaluation stems from the dollar’s role as a “reserve currency.” Japan, China, and others invest hundreds of trillions of dollars in American Treasury bonds and other instruments, pushing the dollar’s value upward. Curing this syndrome through high tariffs and an international accord to weaken the dollar would revive manufacturing with no adverse consequences like inflation.

How is this wrong? Let me count the ways.

Internal Contradiction #1: Miran Wants Both a Strong and a Weak Dollar

Miran simultaneously calls for both a stronger and a weaker dollar. That alone tells us not to take him seriously.

On the one hand, he calls for an international accord to weaken the dollar, backed by threats to hit resistant countries with tariffs and the denial of security protection. He writes: “Scott Bessent [now Treasury Secretary] has proposed putting countries into different groups based on their currency policies, the terms of bilateral trade agreements and security agreements, their values and more. Per Bessent (2024), these buckets can bear different tariff rates....Suppose the U.S. levels tariffs on NATO partners and threatens to weaken its NATO joint defense obligations if it is hit with retaliatory tariffs.” Translation: Nice economy you got here; a pity if something wrecked it.

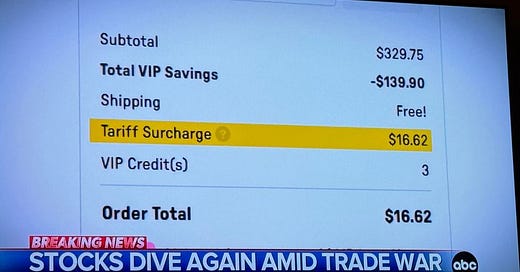

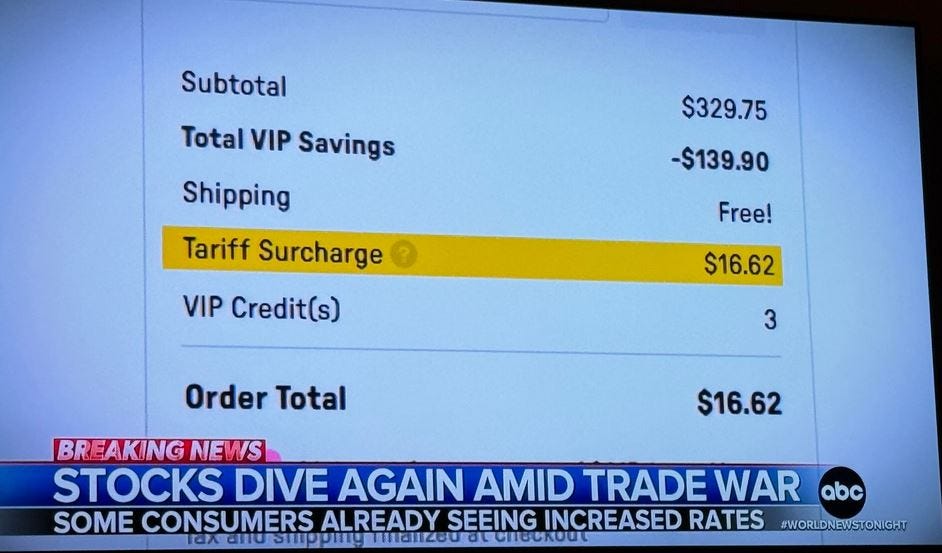

And yet, to back up Trump’s lies that tariffs are paid by foreign countries and would not raise prices in America, Miran says the reason is a move to a stronger dollar. “Tariffs are ultimately financed by the tariffed nation...Tariffs provide revenue, and if offset by currency adjustments, present minimal inflationary or otherwise adverse side effects.” In reality, when America imposes tariffs, they are paid at the border by American firms that either have to absorb the costs or pass them on to consumers. In fact, higher prices are already showing up at stores, and many retailers now inform their customers by putting a “tariff surcharge” on the receipt (see chart at the top). If voters didn’t like the inflation under Biden, they’ll hate Trumpflation and a possible recession.

So here’s Miran’s scenario for preventing Trumpflation. Suppose Trump imposes a 10% tariff. A product that previously cost a dollar will now cost $1.10. But suppose the dollar rises 10%. That will return the price to where it had been (90% of $1.10 equals $0.99). So, the US buyer pays the same price. But here’s what Miran omits. If Americans pay the same price and foreign sellers receive the same price, there will be no import reduction. And yet, the 10% hike in the dollar will make American exports more expensive in overseas markets. So, this worsens America’s trade deficit. Tariffs can only reduce imports if price hikes cause people to buy less.

Internal Contradiction #2: Tariffs Will Help Pay For Trump Tax Cuts

Miran writes that extending Trump’s 2017 tax cuts “may require raising almost $5 trillion of new revenue or debt over a ten-year budget window. Doubtless, tariffs are a big part of the answer for extending the tax cuts; revenue must come from somewhere.” Trade advisor Peter Navarro claims tariffs will give the government $6 trillion over a decade while amounting to a tax cut for the American people. (Rumor has it Navarro also claimed master negotiator Trump has persuaded the sun to rise in the West.)

In reality, tariffs are like taxes on cigarettes. A tax high enough to eliminate all smoking would raise no revenue at all. Similarly, the purpose of tariffs is to reduce imports. The more that it reduces imports, the less revenue it will raise. Conversely, it can only raise a lot of revenue if it fails to reduce imports very much.

False Assertion #1: “Persistent Dollar Overvaluation”

Miran writes: “The deep unhappiness with the prevailing economic order is rooted in persistent overvaluation of the dollar and [resulting] asymmetric trade conditions [i.e., a flood of imports].” Miran simply asserts this alleged overvaluation. He doesn’t even try to present evidence. Perhaps that’s because there is no such persistent overvaluation.

In the chart below, I compare the market value of the yen/$ to its Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). This is a measure of what the value of the yen would have to be so that a Toyota Camry, a loaf of bread, and every other product cost the same in the US and Japan. PPP is often considered a measure of “fair value.” In the half-century, the market value of the yen has been higher than the PPP measure 60% of the time. And, on average, the market yen has been 14% higher than its PPP value. A stronger yen, of course, means an undervalued dollar, not an overvalued one.

Source: PPP from OECD at https://tinyurl.com/24su9pza Note: The shaded area is the “standard deviation, a statistical tool.

This chart shows the dollar’s nominal value vis-à-vis 16 currencies that dominate foreign exchange trading. Again, gyrations around a steady average for the past four decades.

Source: Wall Street Journal

False Assertion #2: “Dollar overvaluation prevents the balancing of international trade.”

Miran and other Trump acolytes contend that, if other countries did not manipulate their currencies or otherwise push up the dollar, no country would ever run trade deficits or surpluses. No mainstream textbook says this. It’s economic illiteracy. As I explained in this post, countries like the US that consume more than they can produce (in terms of personal consumption, business investment, and government spending) have to purchase the excess goods and services from overseas. It’s like a man who catches four fish but wants to eat five; he buys the extra fish from his neighbor. Conversely, countries like Japan or Germany that are unable to consume as much as they produce sell the excess, i.e., run a trade surplus.

False Assertion #3: Trade Deficits Are Why Factory Jobs Fell

Miran writes: “Such [dollar] overvaluation makes U.S. exports less competitive, U.S. imports cheaper, and handicaps American manufacturing. Manufacturing employment declines as factories close.”

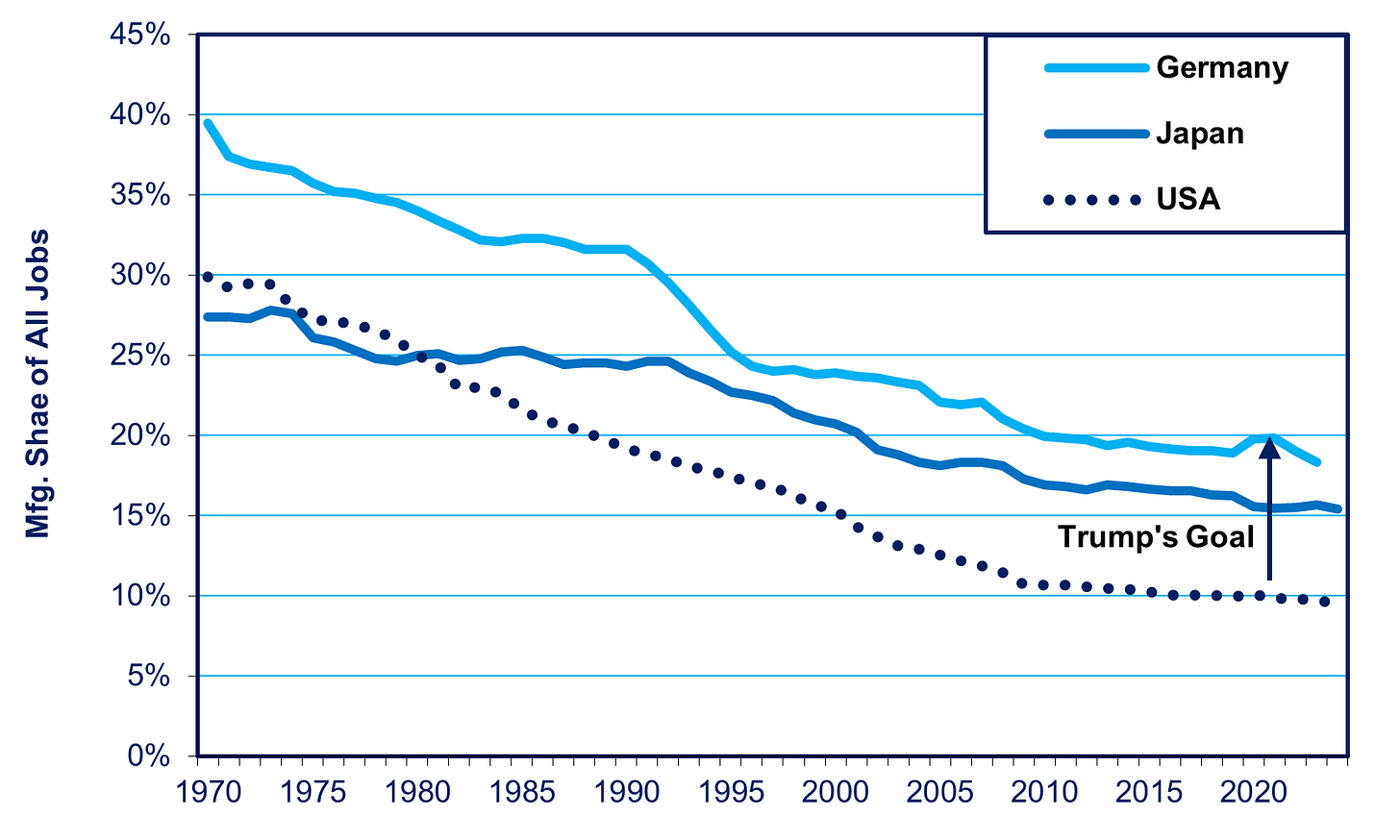

As Miran knows, but deliberately omits, factory jobs have declined in all rich countries, whether they run a trade surplus or a deficit. The first chart shows the decline in the deficit-ridden US, as well as surplus countries Japan and Germany, going back to 1970. In Germany, the share has halved from 40% to less than 20%.

.Source: World Bank, Bureau of Labor Statistics, St. Louis Federal Reserve

The second chart shows the decline in six leading countries going back to 2000.

Source: Our World In Data https://ourworldindata.org/data-insights/manufacturing-accounts-for-a-relatively-small-and-declining-share-of-total-employment-in-rich-countries

This happens for the same reason that farm jobs have shrunk. As countries get richer, customers spend a smaller share of their budget on food and manufactured goods and more on services. At the same time, productivity in both farming and manufacturing is soaring. So, it takes fewer workers to provide the desired food and manufactured goods. In 2015, the United States produced 44% more output of autos and auto parts than in 2000 (measured in real billion dollars), but with 30 percent fewer workers. That means one autoworker could produce as much as two workers in 2000. To prevent a decline in automotive jobs, customers would have to have bought twice as many cars. Even if there had been no trade at all, jobs would still have fallen 27%.

Many countries have tried, and failed, to resist this fundamental trade by boosting their trade surplus. Trump, like the fabled King Canute, is demanding that the waves retreat.

False Assertion #4: High Tariffs Will Bring Back The Lost Factory Jobs

As early as Trump’s first term, his trade advisor Peter Navarro proclaimed that they intended to double manufacturing jobs to 20% of all jobs just by eliminating America’s trade deficit. The logic was that, with the trade deficit gone, American and foreign companies that wanted to sell in America would have to build in America.

Who is supposed to fill all these jobs? For factory jobs to double, 10% of the labor force would have to shift from whatever they are now doing to fill those jobs. So, that means fewer teachers, firefighters, hospital workers, retail salespeople, auto repair mechanics, postal workers, and so forth, And that means less of those services.

Already, manufacturers cannot find enough employees for all sorts of jobs, including industrial engineers. Deloitte calculates that the shortfall could rise to 2 million workers by 2033. Companies like Japan’s MinebeaMitsumi say they hesitate to invest in the US because of this labor shortage. The Trumpers do not let such real-world realities disturb their pipe-dreams.

Worse yet, high tariffs will hurt manufacturing. In 2022, imports provided a full 20% of all the inputs to factory output, including lots of parts and machinery. Hence, high tariffs will raise the cost of making products in the US, thereby reducing America’s exports. Workers will suffer since exporting companies pay 20% higher wages than others. It will also make it harder for American consumers to afford these products, e.g., by raising the price of a car by thousands of dollars. Look at the record. While Trump’s first set of steel tariffs boosted steelworker jobs by 26,000, they destroyed an estimated 433,000 jobs in the rest of the economy, mainly in steel-consuming industries like autos and home appliances.

Sophistry #1: We Live in a “Triffin World”

Miran offers the illusion of sophistication by saying his arguments are all based on the famous “Triffin dilemma,” named after the economist who presented this thesis back around 1960. In reality, it’s more sophistry than sophistication. The Triffin dilemma did apply in the world of fixed currency rates, and he correctly predicted that this system would break down, as it did during 1971-73. But it no longer applies in the world of floating rates that has existed for the past half-century. Miran is playing games when he asserts we live in a “Triffin world” that forces dollar overvaluation and chronic trade deficits for the US. At the time Triffin presented his view, the US was running chronic trade surpluses, not deficits. Triffin was worried about dollar depreciation, not overvaluation. The “reserve” status of the dollar at the time of fixed currencies had a function in other countries’ money supply that it no longer has. There were capital controls and relatively little flow of private capital at that time. Triffin was worried about capital outflows from the US to supply dollars, not the capital inflows of which Miran complains..

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To provide more support, donate several subs at $50 each. You do not need to name the sub recipients, just how many. This is a one-time contribution; it does not repeat automatically. Please click the button below.

Beautifully written Richard

Typo run for sun. Otherwise spot on. Ideology trumps common sense. Who was it that said: This is the USA, we can do what we want. The rot has properly set in.