Postponomics: Kishida Punts On Startups and Income Redistribution

Decision Postponed On Tax Breaks for Startups, No Hike in Corporate Tax

Source: OECD at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz417hj6hg6-en

The most important sentence in the Kishida Administration’s just-issued “Five-Year Startup Development Plan” is the delay of any decision on the tax breaks that are indispensable for promoting more startups. “Tax measures will be considered in the future tax reform process,” says the plan [emphasis added; unofficial translation].

Meanwhile, Tokyo has also delayed until 2027(!) full-fledged implementation of any hikes in the corporate income tax, or any other taxes, to fund the near-doubling of defense spending over the coming five years. Moreover, said Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki at a Dec. 6 press conference, has delayed until at least next year any decision on such taxes. In the meantime, it will rely on promised cuts in spending and assured expansion of budget deficits. Whether any decision will actually be made next year, or there will be further postponements, remains to be seen. There is a lot of resistance by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) to hikes in the corporate tax and within much of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to hikes in any taxes. Sometimes in Japan, delaying a decision, or saying “we will consider it,” is a way of saying no without admitting as much. As I’ve discussed in previous postings (here and here), a hike in the corporate tax is one of the necessary ingredients in Kishida’s pledge to rebalance national income between corporations and households.

While high-flown rhetoric and lofty promises remain in place, the substance of Kishida’s “New Capitalism” has been replaced by “Postponomics:” a vague promise to consider the possibility of taking some sort of action at some indefinite moment in the future. (The term “Postponomics” was coined by journalist Regis Arnaud.)

This is truly disappointing. A few weeks ago, conversations with policymakers in assorted Ministries and the Prime Minister’s Office had given me hope that, while a hike in the corporate tax was becoming increasingly difficult, there would at least be some action on two of the half-dozen or so tax breaks needed to help promote startups. Not sufficient action, but at least something of substance. Those two included: tax breaks for “angel investments” (to be explained below) and stock options for employees.

However, attaining these tax incentives required strong insistence by the Prime Minister to overcome rigid opposition to any tax breaks—no matter how helpful to economic growth—within the Ministry of Finance (MOF) Tax Bureau and its allies in the LDP Tax Commission. That insistence never came. On the contrary, Kishida is so indecisive that he is increasingly being nicknamed “kento-san” derived from the verb “to consider.” One business executive said that, in his circles, Kishida’s nickname is “the puppy,” i.e., he is eager to please that he will not step on any toes in pursuit of needed action. Whether or not one liked the policies of Shinzo Abe and Yoshihide Suga, there’s no question that they were willing and able to compel the Ministries to accept the policies they prioritized.

Startups Can’t Grow Without Funding

Kishida’s Five-Year Plan sets a goal of nurturing 100,000 innovative, high-growth startups over the coming five years. It’s a worthy goal. The single biggest obstacle to achieving it is a dearth of outside financing that these companies need to fund growth. Japan. So, while many other measures are necessary—and there are some in the Five-Year Plan— they will prove insufficient without a breakthrough on the funding front.

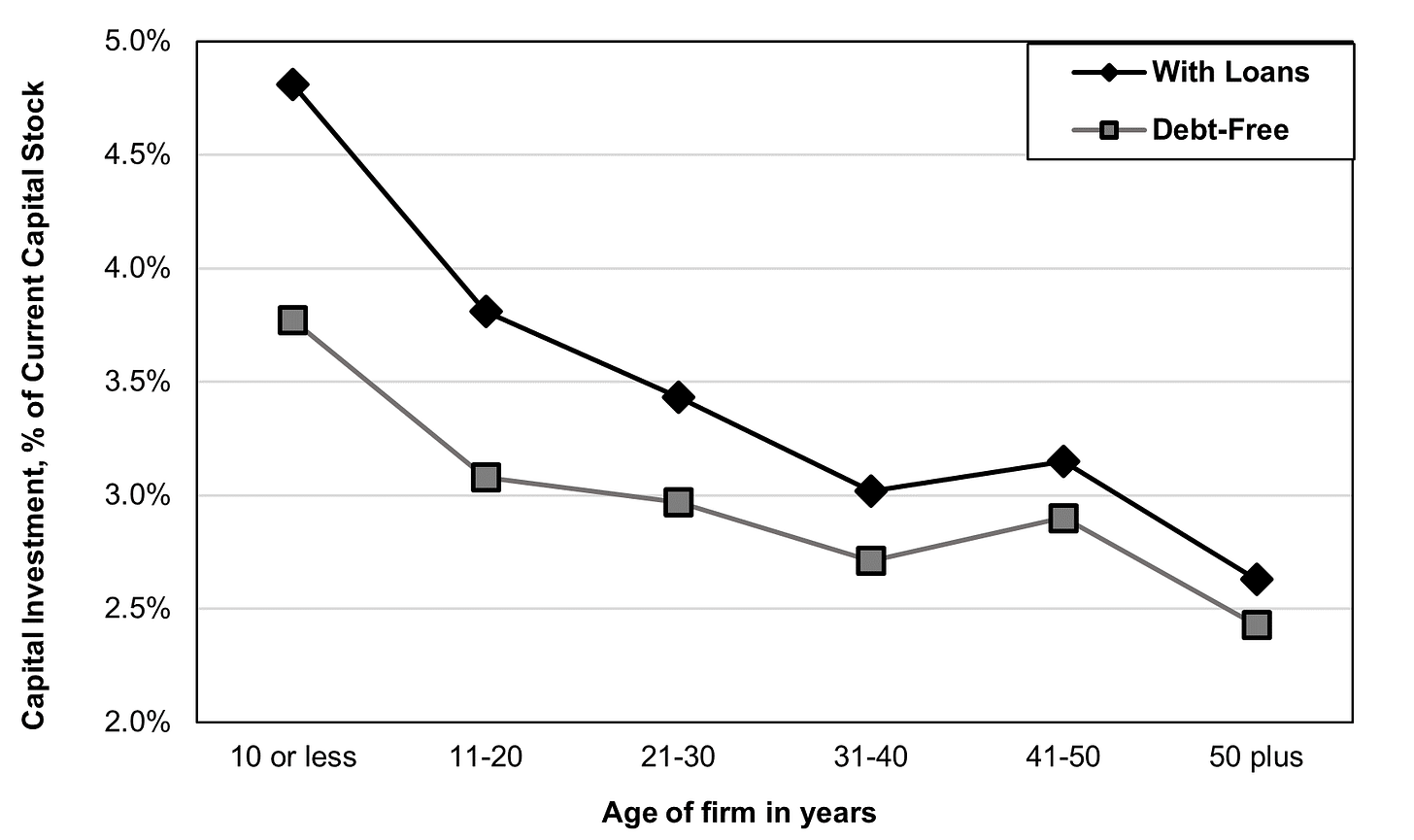

To be sure, Japan engenders a lot of new companies with growth potential. The problem is assorted impediments to growth. New companies in Japan suffer the least growth among rich countries in the OECD (see chart at the top). New firms used to list financing and recruiting staff as the biggest obstacles. Staffing is becoming easier but accessing outside money is as hard as ever, and far harder than in other rich countries. And this makes a big difference in how much new companies can grow in the early years. For example, Japanese companies without access to loans cannot invest as much in expansion and modernization, a problem particularly severe among companies under ten or twenty years old (see chart below). Moreover, new companies that don’t get big enough fast enough tend to fail far more often.

Source: METI. https://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/pamflet/hakusyo/H28/PDF/2016shohaku_eng.pdf, pg. 340

Note: If a firm has ¥100 million worth of plant, equipment, and software, and adds another ¥5 million in a given year, the investment ratio is 5%.

What Should Japan Do?

There are at least a half dozen major measures the government could undertake that could have a major impact on rectifying this flaw. Let me point out just two.

“Angel” tax credit. While many people are familiar with Venture Capital, fewer are aware of “business angels” who invest money in innovative firms where VC money is inappropriate. In 2019 in the US, angels invested a total of $24 billion in 63,730 companies, 20 times the number of companies who received VC money. Equally important, well-designed tax breaks increased the volume of angel investments. After Wisconsin enacted a 25% tax credit in 2005, total angel investments jumped tenfold. Japanese experts have proposed emulating the UK’s successful Enterprise Investment Scheme.

Angels, unfortunately, are scarce in Japan. While Japan has had a tax break for angels investing in certain fields ever since 1997, the system has been made virtually useless due to the limitations on the age of the firm (no more than three years) and maximum tax deduction of a piddling $100,000 for an angel’s total investments (rather than in each company). That maximum is dwarfed by the typical size of angel investment in each company in the US, which in 2019 was $$376,000 invested in nearly 64,000 companies. Some improvement has been made regarding the age of the firm and other eligibility matters. However, the MOF has repeatedly blocked METI’s efforts to expand the size of the credit. It did so again this year.

R&D Tax Credit Carry-Forward. Even companies not in high-tech conduct a lot of Research and Development (R&D) and the new companies that do so expand more. Yet, 92% of all Japanese government aid goes to large incumbent firms, the worst ratio in the OECD (see chart below).

Source: OECD at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888933064601

The reason is that almost all the aid goes through tax credits, rather than subsidies. But a tax credit only aids companies that are already earning profits. New, growing companies take years to become profitable and so are ineligible. To remedy this, most countries apply a “carry-forward” which allows the company to use the credit when they become profitable 10 or 20 years down the road, or even later in some countries. That carry-forward helps them attract more outside investment funds. Japan, however, has no carry-forward at all.

For those interested in a few more examples—ending double-taxation of the dividends of Limited Liability Companies, the open innovation tax system, and making stock options less cumbersome, and expanding government procurement from innovative startups—see this addendum.

The Hollowness of the Five-Year Plan

When I talked to policymakers in Japan, they assured me that expanding the angel tax credit was on the table. METI was pushing for it. In the end, however, the Five-Year Plan says not a word about expanding the tax credit for angels. All that remains is talk that, “we will consider simplifying the procedure and making it online, such as reducing the application documents required to receive tax incentives.” I have gotten some indications of the politics of this outcome and will report when I pin it down.

Worse yet, METI did not even recommend some of the other needed taxes, such as the R&D carry-forward or ending the double-taxation of LLC profits. My sense was that METI reached the political conclusion that an expansion of the angel tax credit was the most it could get, and it is not clear how hard it pushed on that.

The Five-Year Plan also mentions measures to encourage individuals such as founders to invest in startups by establishing “a preferential tax system when selling shares held and reinvesting in startups.” One official compared this to the Qualified Small Business Stock system in the US. But this mostly helps the relatively affluent founders who have enough assets to make their firm grow; it doesn’t bring in enough outside money in the early years in the way an expanded angel tax credit would.

METI also pushed for regulatory changes in stock options for employees and appears to have succeeded at least somewhat. Getting regulatory changes is easier than tax breaks. The purpose is to make it easier for startups to attract talented employees even before they can afford lucrative salaries. For more details, see the addendum.

Conclusion

Many changes in society are increasing the number of startups with growth potential: from generational changes in attitudes to technological changes that open more opportunities for new firms. However, it will take government action on various fronts for these important trends to reach a critical mass that will help the entire economy. Unfortunately, Kishida, like Shinzo Abe in his “third arrow” reforms, is “big talk, little action.”

The more hierarchical a society is, the more people feel helpless and this leads to fatalism and apathy.

This is the predictable outcome, when you have a one-party "democracy" run by and for corporate interests where the people are apathetic and disengaged, and have long since surrendered aspirations for civil rights, democracy or self-realization for a job that forces them to expend all of their psychological energy avoiding putting a foot wrong or causing offense, and a vague promise of things not getting too much worse too fast, as long as they toe the line.