Road to Recovery: Creative Destruction Vs. “Greenfield” Foreign Direct Investment

Dialogue with Noah Smith, Part 2

Photo:Fumishige Ogata

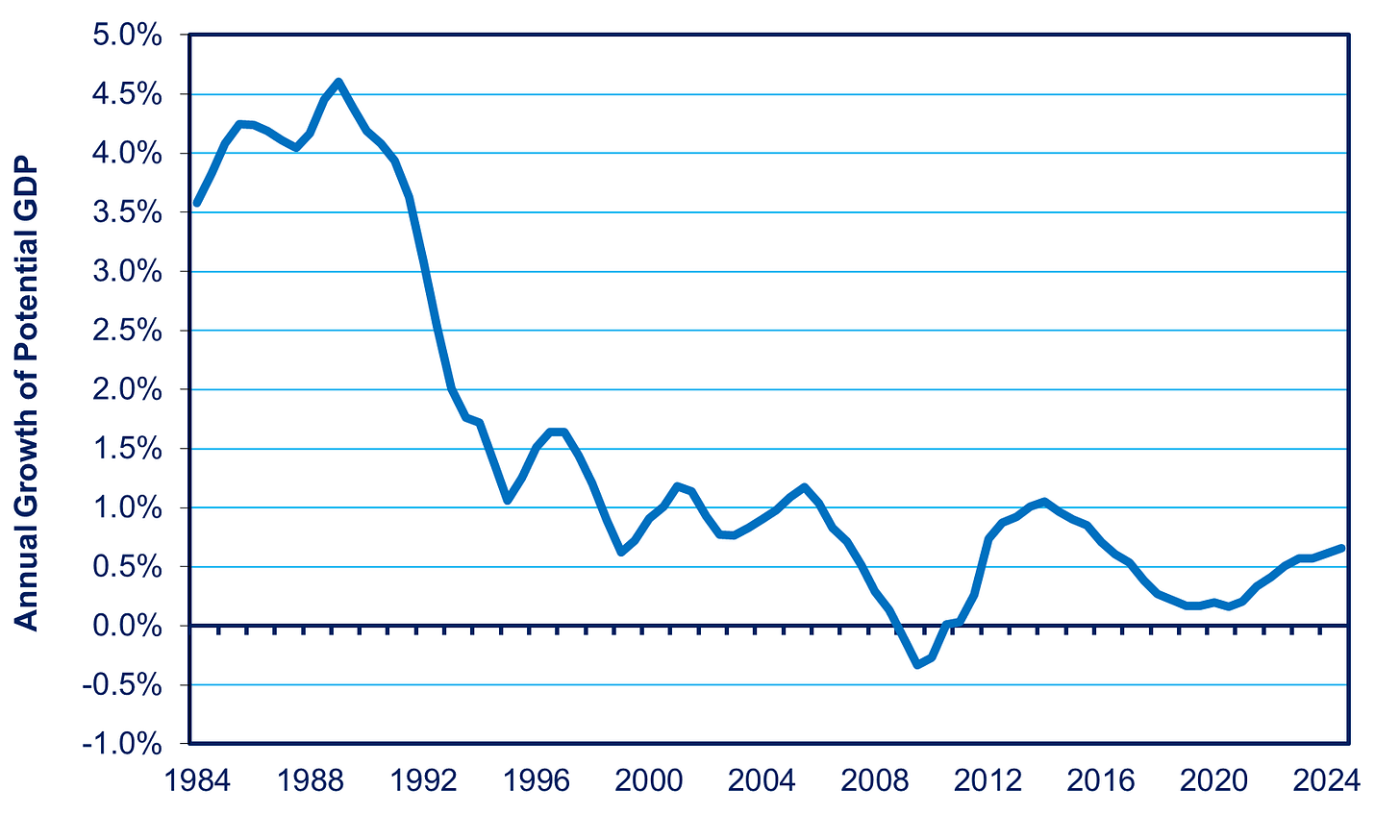

What is the best path to upgrading Japan’s GDP growth rate at full employment, now estimated by the Bank of Japan at around 0.7% per year (see chart below)? How could Japan raise its growth per capita to 1.5% or 2%? That is the subject of the second part of the dialogue between myself and famed economist Noah Smith. (Click here for the first part.) It was done on the occasion of the simultaneous publication of the Japanese translation of my book, The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future: Entrepreneurs Vs. Corporate Giants and Smith’s book, Weeb Economy: The Weebs Will Save Japan. Weebs are fans of Japanese culture.

While Noah and I agree on most issues regarding Japan, this is a topic where we disagree. I emphasize the need for “creative destruction,” i.e., the replacement of older inferior firms by better ones. The “better ones” include not just domestic firms, but also foreign firms that invest in Japan. The latter can either set up their own operations or buy and improve Japanese companies (i.e., inward Foreign Direct Investment, or FDI). (For more on the benefits of inward Foreign Direct Investment, see Japan Still 196th In Inward FDI.) Noah disagrees for a few reasons. Firstly, he thinks creative destruction is less prominent in healthy economies than I do. Secondly, he places much more emphasis on inward FDI of a particular type: foreign firms setting up new “greenfield” facilities in Japan. He thinks there are few benefits from foreign firms buying Japanese firms, or even mergers in the same country. Here is this part of our dialogue. Toyo Keizai journalist Misa Kurasawa moderated the discussion. (For the first part of our dialogue in Toyo Keizai in Japanese, click this link.)

Source: https://www.boj.or.jp/en/research/research_data/gap/gap.xlsx Note: Potential GDP means GDP with full employment and full use of physical capacity

Katz: Noah, we agree that Japan’s problems are fixable. But we have some differences about how to do that. My view is that, in every country, a healthy economy needs “creative destruction.” That is, the continuous replacement of older, inferior companies by newer, more innovative companies. In rich countries, that turnover provides 30-40% of the productivity growth that improves living standards. Unfortunately, Japan has one of the lowest rates of firm turnover among rich countries. It preserves many inferior firms while making it hard for dynamic new companies to emerge. That’s one reason growth is so anemic.

Japan suffers from “old company disease.” Older companies find it hard to change or even recognize that times have changed.

The good news is the generational, cultural, and technological changes we discussed in part 1. For example, it used to be very hard for new companies to recruit talented staff because of the lifetime employment system. That has opened up a lot, especially among the 25% most talented people. The rise of e-commerce has given new companies better access to potential customers, reducing the power of the old distribution system to block them.

Access to finance, however, remains a huge obstacle. Without it, companies cannot grow. Banks charge a lower interest rate to a company they’ve worked with for 50 years than a company that's 10 years old with a good credit rating, but little collateral. Younger companies often have more human capital than collateral.

Government policy can help, but there’s been more rhetoric than action so far.

92% of Tokyo’s financial aid goes to large companies that are cash-rich and don’t need help. More should go to newer companies. But all the assistance comes via a tax deduction on corporate profits. But it takes years for new companies to become profitable. Other countries solve this problem by having a 20-year (or longer) tax carryover, so that, once a company becomes profitable, it can use the tax credit. That makes the firm more attractive to early investors. But Japan has no tax carryover at all.

The government spends almost 20% of GDP buying goods and services from companies. Japan has a big set-aside for small companies, but only a tiny 3% of national-level procurement set-aside for new companies, and it has never come close to reaching that. Achieving this would increase company revenue, making banks more willing to lend.

Smith: Many people in Japan are afraid that building new sectors of the economy will destroy many jobs in these old companies that are driven out of business. In reality, startups rarely replace old companies in their sector. Instead, economies grow by adding new sectors.

Look at the top 100 companies in America. Most of those companies were there a hundred years ago, or 70 years ago, such as Procter & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson, GM & Ford, and General Electric. Some shrink, but they rarely die. Instead, new companies in new sectors now take the lead, like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Nvidia, and so forth.

As the new sectors have emerged, we’ve seen an increase in the percentage of Americans who have professional jobs: management, you know, engineering of all sorts, and other professions.

The message that you need creative destruction is too scary. Yes, you do need to let companies die when they fail. But if you look at the big picture of the future, it's not that the old economy dies and the new economy rises in its place.

Katz: I disagree. Of the 500 companies in the S&P 500 in 1957, 300—60%- no longer existed 50 years later. They either closed altogether or were acquired by a different company. Amazon is not in a new sector; it’s just a retailer using a new technology. Its website has driven some old brick-and-mortar retailers out of business, including giants like Sears. Netflix is just an electronic movie theater. Old sectors using new technology are an even bigger source of growth than the new sectors that produce that technology. Moreover, it’s often new companies that pioneer the use of new technology in old sectors, e.g., Tesla and BYD in Electric Vehicles. In the typical rich country, 8-10% of all companies, big and small, die every year and are replaced by better ones. In Japan, it’s only 4%.

My message is that, to make creative destruction politically palatable, you need a strong social safety net that helps people transition from job to job and company to company. You also need to help adults upgrade their skills. Japan and the US spend the least on these sorts of measures. The result in Japan is slow growth; the result in the US is Donald Trump. The Scandinavians have done this better than anybody in a system they call flexicurity.

Smith: The flexicurity system is probably the best social safety net humans have ever invented. If you lose a job, they help you find another. So long-term unemployment is lower in Denmark and Sweden. Denmark doesn't do everything right: its tax rates are too high, and it’s too socialistic. You can always learn from pieces of other countries, but not the whole thing. There are still things that America does well that people could learn from.

Katz: Since the Meiji Era, Japan has been very good at learning from others while adapting features to Japanese conditions.

Kurasawa: Both of your books talk about how Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is vital to recovery and innovation, but you have different approaches to that.

Smith: The traditional model of FDI in rich countries is that a foreign company would want to sell stuff in some overseas market. So instead of establishing their own operations here, they would buy a company in that country. I think this kind of M&A is, on average, not very useful. Japan was correct to be wary of this. My reason is that this kind of merger and acquisition (M&A) typically destroys value. It's usually a corporate mistake, even when an American company is buying another American company.

What Japan needs is “greenfield” FDI where a foreign company will build a factory in Japan, like the TSMC semiconductor factories in Kumamoto, or will build a research center in Japan, like the Samsung Research Center. Or a foreign venture capital firm will help fund a startup in Japan, like Lux Capital helped fund Sakana AI.

This year, Poland's real GDP per capita will exceed Japan's. Poland’s success was built entirely on FDI. You can't name a Polish brand. It's not M&A because there were no Polish companies to buy. It's all greenfield.

Katz: Let me interject that, without inward FDI, the Chinese economic miracle would never have been so spectacular. Deng Xiaoping created “socialism with Japanese and Singaporean characteristics.” From Japan, Deng Xiaoping learned that you can have industrial policy, but it has to be executed through private companies, not state-owned ones. And from Singapore, he learned you need FDI. In China, FDI was mostly either greenfield or joint ventures. Xi Jinping is reversing Deng’s reforms in these areas, thereby killing the geese that laid the golden eggs.

Smith: Greenfield investment is one of the big holes in Japan's economy. Every top company in the world wants to build stuff in the United States, but they are not building in Japan. They should be. Every company in cars, high-end appliances, aerospace, semiconductors, AI, etc., should be in Japan. Filling this hole is not a replacement for startups or old companies. It's just a new addition. Build this new big thing and watch GDP go up.

Katz: I don't think it's either/or, i.e., greenfield investment or M&A. It’s both. More than 80% of inward FDI in rich countries and emerging markets is M&A. So, I'm all for greenfield investment, and the Japanese government is trying to get that. But, for now, Japan’s inward FDI of all kinds as a share of GDP is 198th out of 200 countries, worse than North Korea.

As for M&A, studies of Japan have shown that Japanese companies with more foreign ownership, including a controlling interest, have improved their performance. Moreover, via spillover effects, that process has also improved the efficiency and innovativeness of their suppliers, customers, and even competitors.

The reason is that FDI, whether greenfield or M&A, brings in fresh ideas. When the Japanese auto companies built their plants in the United States, it forced improvement in the Detroit Three. When Japanese domestic companies see a foreign-owned company operating differently and succeeding, they learn from it. When some Japanese employees of foreign companies go out and start their own companies or move to a different company, they spread ideas.

Smith: When FDI is done via M&A, very few employees are transferred to Japan from overseas. When foreign companies buy Japanese companies to try to sell into the Japanese market, they usually think this company knows how to do that, and just let them do it. But, often, the targets for these mergers and acquisitions don't have a great corporate culture. And a couple of people transferred from overseas aren't going to fix it.

Katz: The newspaper headlines are full of cases of rescue operations, e.g., Foxconn buying Sharp or Renault buying Nissan. However, in most cases, foreign companies want to purchase healthy companies, not companies needing a fix. They want to tap the Japanese market, even the Asian market, and sometimes even exchange various technologies and strategies in order to upgrade the parent company all around the globe.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To provide more support, donate several subs at $50 each. You do not need to name the sub recipients, just how many. This is a one-time contribution; it does not repeat automatically. Please click the button below.

This was a great conversation. I wish I was at the table. I'm currently looking to take one of my businesses public in Japan, and another exit from an M&A in the next 3-4 years. I founded my first startup in Japan in 2004, and the change for the better for new businesses is obvious. However, as mentioned in your conversation, access to funds is very difficult in Japan. Not everyone wants to or has access to VC money. The government is dropping the ball here. Another opportunity Japan has is to lean into English. The country's population is declining, so each working person becomes more valuable. If English became the second language of Japan, there would be no limits to the growth that could happen here. Probably impossible, but it's there on the table.