The BOJ, the Fed, and The Future Of The Yen

Yen May Not Recover As Much As Some Expect

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10 and https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DFF Note: See text for explanation

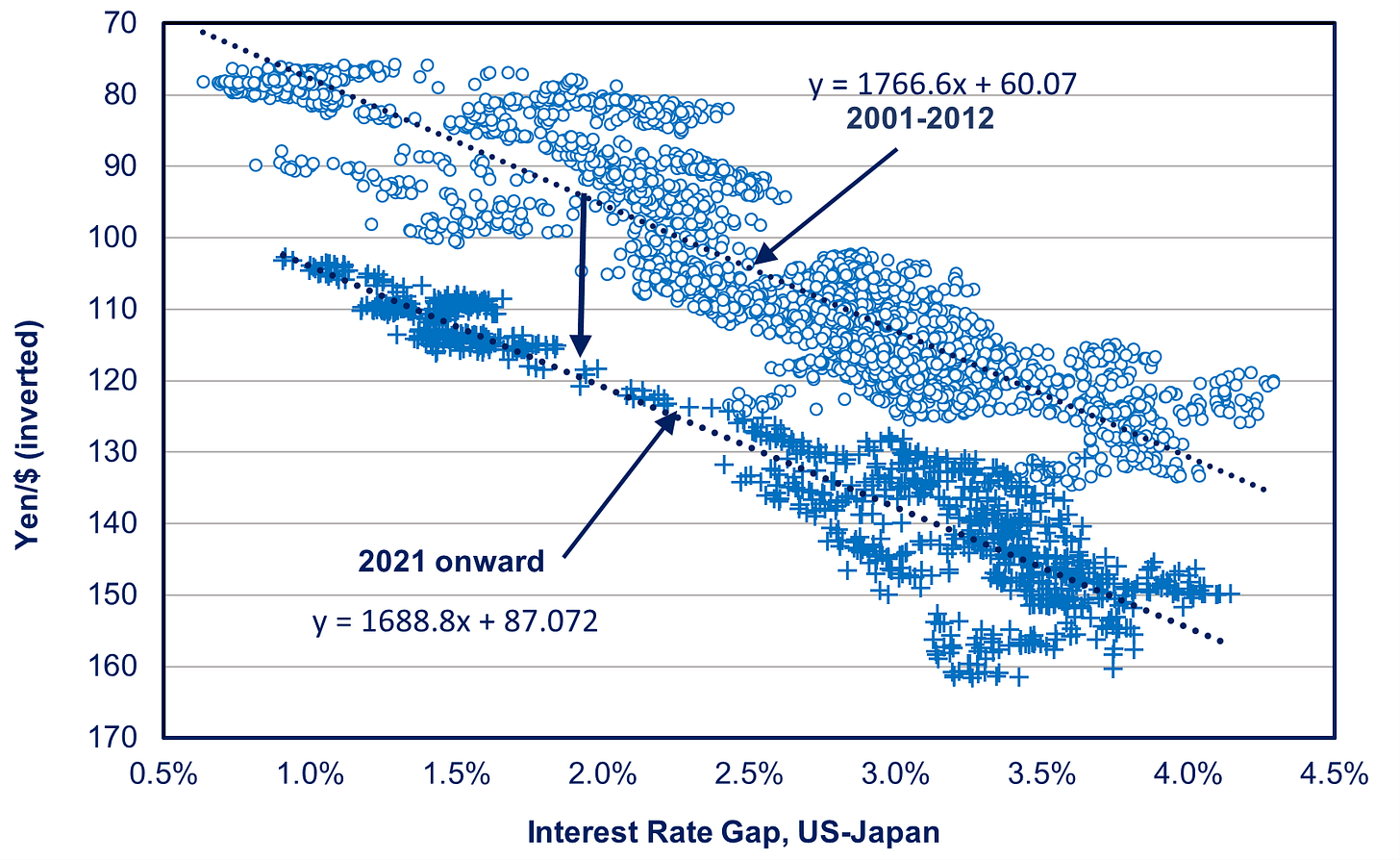

Many traders and economists believe the yen will recover quite strongly now that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is raising overnight interest rates while the Federal Reserve is cutting them. The logic is that the narrower the gap between American and Japanese interest rates, then the less money is lured from Japan to the US, and therefore, the stronger is the yen vis-à-vis the dollar. In fact, the ups and downs of the gap between 10-year government bond rates in the two countries explains nearly 90% of the ups and downs of the yen’s value during the nearly four years since January 2021. There is, however, a fly in that ointment. Implicit in these yen forecasts is the premise that, as the gap between overnight rates in the two countries narrows, so will the gap in the 10-year bond rate. However, as detailed below, changes in overnight rates may have little impact on long-term rates, and thus on the yen/$ rate.

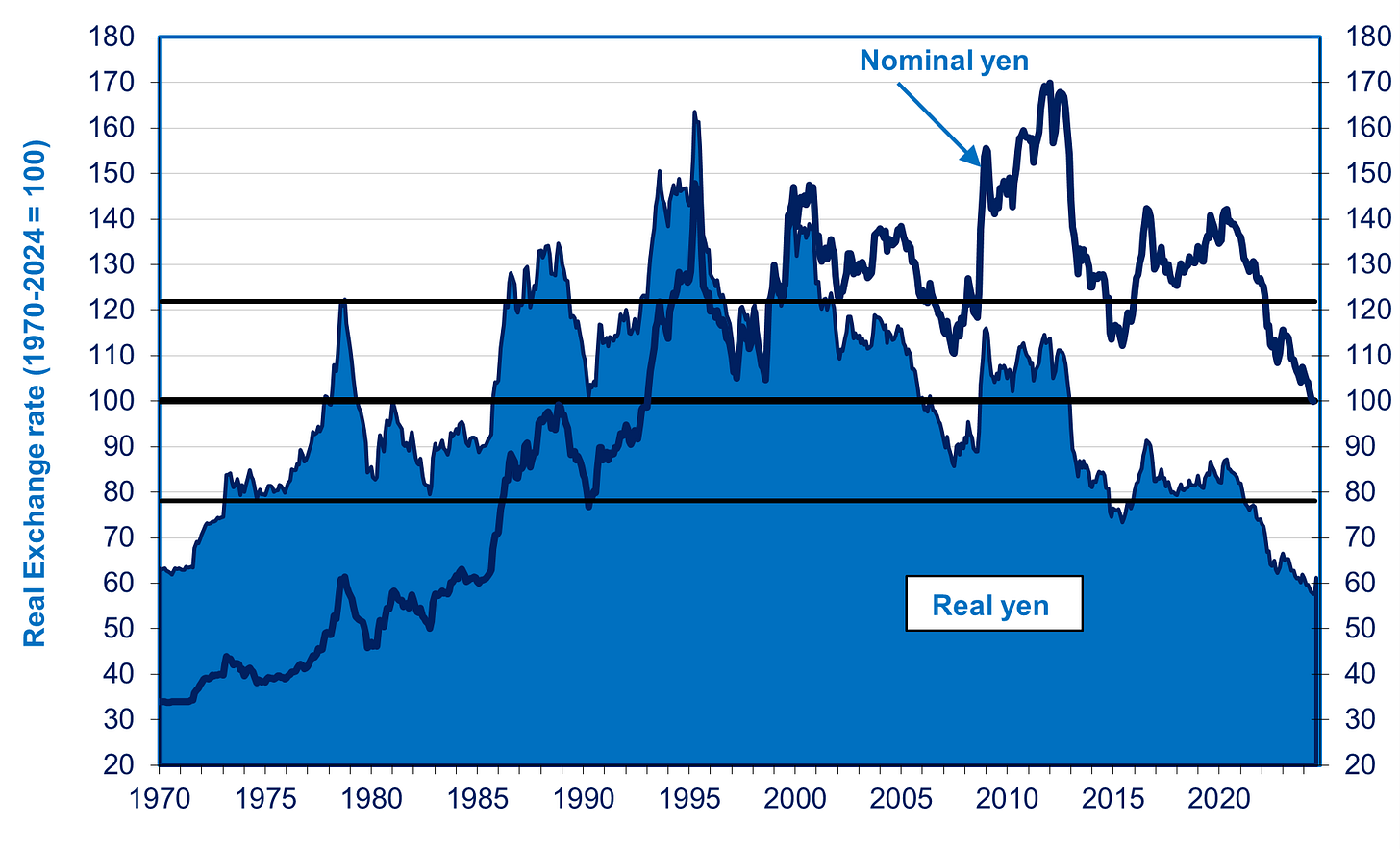

There is a second, more fundamental issue. Because of the long-term deterioration in the underlying competitiveness of Japan and its exporting companies, the real yen against all of Japan’s trading partners has suffered a three-decade depreciation of nearly 60% since 1995. Unlike the nominal yen, the real yen takes into account differing rates of inflation between Japan and its partners and thus shows Japan’s real competitiveness in international markets. Unlike 1970-1995, when Japan was becoming more competitive, its ability to compete has reversed and is now the lowest since a half-century ago (see chart).

Source Bank of Japan

Japan is like a once-stellar company that now must cut its prices to be able to sell its products, and an ever-cheaper yen is the vehicle for cutting export prices in dollar terms. As a result, even if the long-term interest rate gap were to return to former levels, that would not bring the yen/$ back to past levels. Suppose, for example, that the ten-year rate gap, now at around 3.0 percentage points, fell to 2.0 points. Back in 2000-2012, that would have translated into around ¥95/$. Today, it would result in ¥120/$ more or less (see chart below). For details, see this post and my Financial Times op-ed.

Source: Author calculation based on data from Wall Street Journal Note: The yen value on the left axis is inverted so that a lower trend line means a less valuable yen; see text for further explanation

Narrowing the Gap In Overnight Rates

The most hawkish member of the BOJ Policy Board, Naoki Tamura, says the BOJ should raise overnight rates to 1% sometime between October 2025 and March 2026, up from 0.25% today. Let’s assume this is the highest rate that the BOJ will go over the next couple of years. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve expects to lower the overnight rate, known as “fed funds”—from 5.25% a few weeks ago to around 3.4% by the end of 2025, 2.9% by the end of 2026, and keep it there. If that happens—there is no guarantee—the gap between US and Japan overnight rates will have more than halved from around 5% early this year to just 2% by the end of 2026. That’s a big change. But, as detailed below, it may not narrow the gap in ten-year interest rates, and thus have little impact on the yen.

US Ten-Year Rates Won’t Drop Just Because Overnight Rates Do

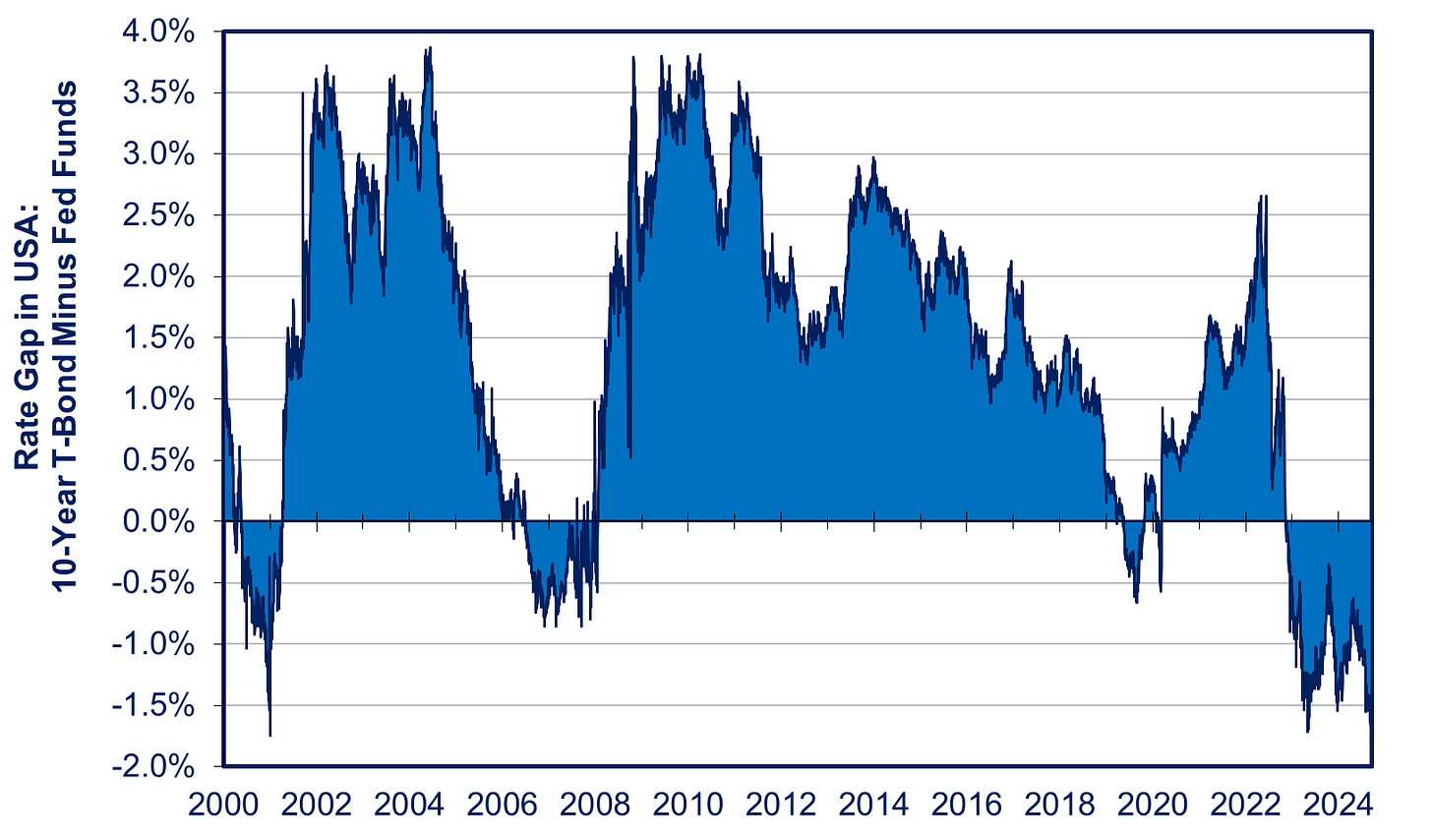

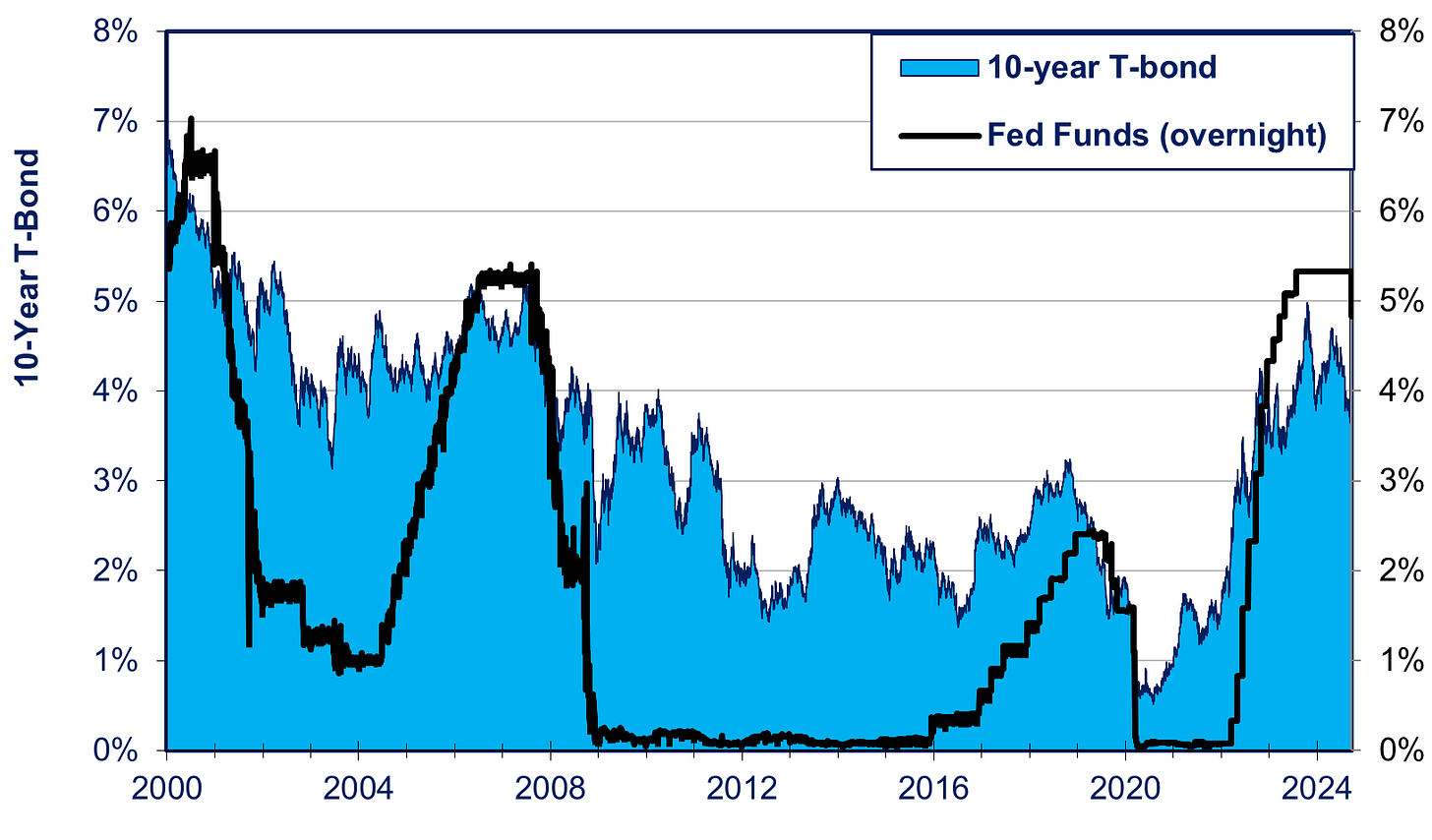

On the US side, the cut in fed funds may not yield any cut in ten-year rates. That’s because the normal relationship between overnight and ten-year rates has been greatly distorted and is now returning to normal. Over the past quarter century—except when the Fed was fighting inflation and/or the market expects a recession—rates on ten-year bonds have averaged around 2% or so above the fed funds rate. But in the past couple years, the ten-year rate was in the abnormal position of being below the overnight rate by around 1-to-1.5 percent points (see charts at the start of this post and below).

With inflation and overnight rates normalizing, ten-year rates will return to being higher than overnight rates. Indeed, in the August Wall Street Journal survey of more than 70 professional forecasters, the average respondent expected virtually no change in ten-year bond over the next couple years. Today, the rate stands at 3.8%. The forecasters predicted a rate of 3.85% in December 2025 and 3.8% in December 2026.

Great Uncertainty About Japan’s Long-Term Rates

Whatever uncertainty exists regarding long-term rates in the US, it’s dwarfed by the contentiousness surrounding the prospects for the interest rate on ten-year Japan Government Bonds (JGBs).

At the very bullish end of the spectrum, Goldman Sachs sees the ten-year JGB interest rate hitting 2% by the end of 2026. But that’s based on the assumption that Japan achieves 2% inflation and that overnight rates rise to 1.25% or even 1.5% by 2027—a rate even higher than that advocated by the BOJs most hawkish member (1.0%). The OECD foresees 1.6% by the end of 2025. If these forecasts were to come true, the rate gap would narrow from 3 percentage points today to about 2 points. This, as discussed above, would trigger a substantial strengthening of the yen from today, but to a level far weaker than 20 years ago.

There are, however, two problems with these predictions. Firstly, there is no guarantee of 2% inflation in 2025-26 (see my last post). Secondly, even with 2% inflation, there is a big chance that ten-year JGB rates will remain substantially below 2%.

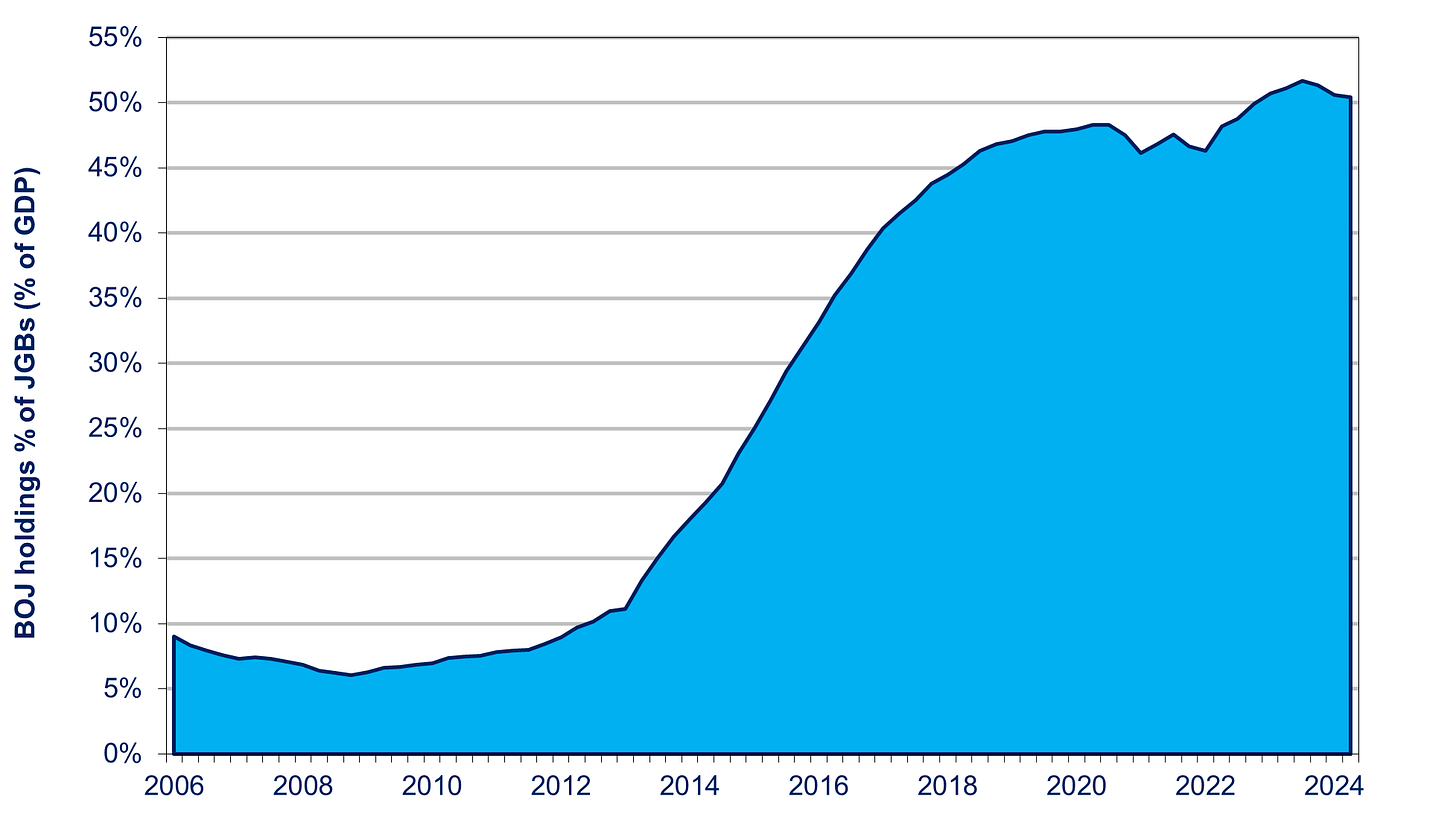

The interest rate is a price—in this case, the price of credit—and, like all prices, it is determined by supply and demand. From 2016 until a few months ago, the BOJ determined the “price” by adding to demand on a monumental scale. That led to the BOJ ownership of JGBs zooming to half. That kept interest rates at 0%. In October of 2023, it began transitioning away from that policy by reducing its purchases of JGBs, but very slowly (see chart below). It intends its total holdings of JGBs to drop by around 8% by the end of 2026, a pace intended to keep JGB rates from surging.

Source: MOF and BOJ

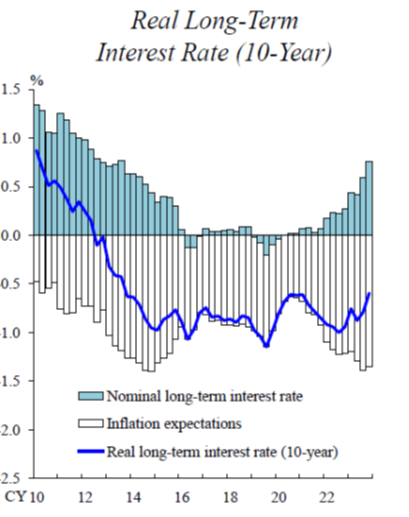

In fact, in recent speeches, BOJ Policy Board members have repeated the mantra that, “In the case of a rapid rise in long-term interest rates, the Bank will make nimble responses by, for example, increasing the amount of JGB purchases.” Meanwhile, in a major speech in February, Deputy Governor Shinichi Uchida stated that both short- and long-term interest rates were expected to remain negative—i.e., below the inflation rate—for a while (see chart below). The implication? If inflation stabilizes at 2% as the BOJ expects, then the interest on ten-year JGBs would have to remain substantially below 2%.

Source: https://www.boj.or.jp/en/about/press/koen_2024/ko240208a.htm

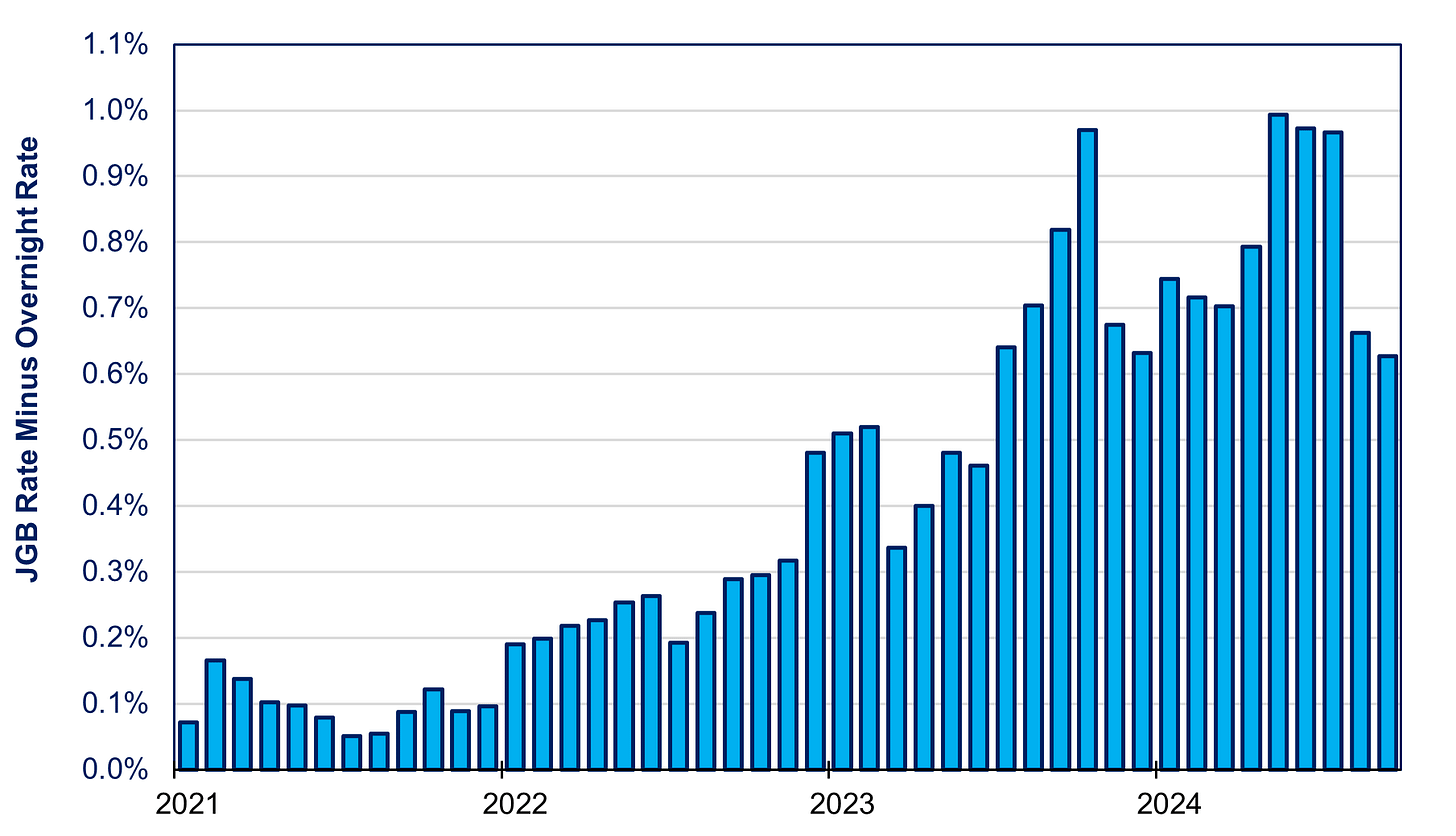

That is one reason that the 10-year JGB rate today is just 0.85%, no higher than a year ago. More importantly, as the BOJ raised its overnight rate at the end of July to 0.25%, the differential between JGB interest rates and overnight rates fell to 0.66% in August and just 0.63% in September (see chart below). This differential will be an important leading indicator. If the differential stays around 0.6%, or declines even further, it will suggest that, even if the overnight rate eventually hits 1%, the JGB rate will not get even close to 2%.

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IRSTCI01JPM156N and https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IRLTLT01JPM156N

Private Market Forces: Chronic Low Demand for Credit

There is a more fundamental economic condition behind the BOJ policy: weak demand for credit in the private financial markets. When the private demand for credit is too low to absorb the supply of savings, then the interest rate has to soften until supply and demand equalize. In Japan, demand for credit is very low.

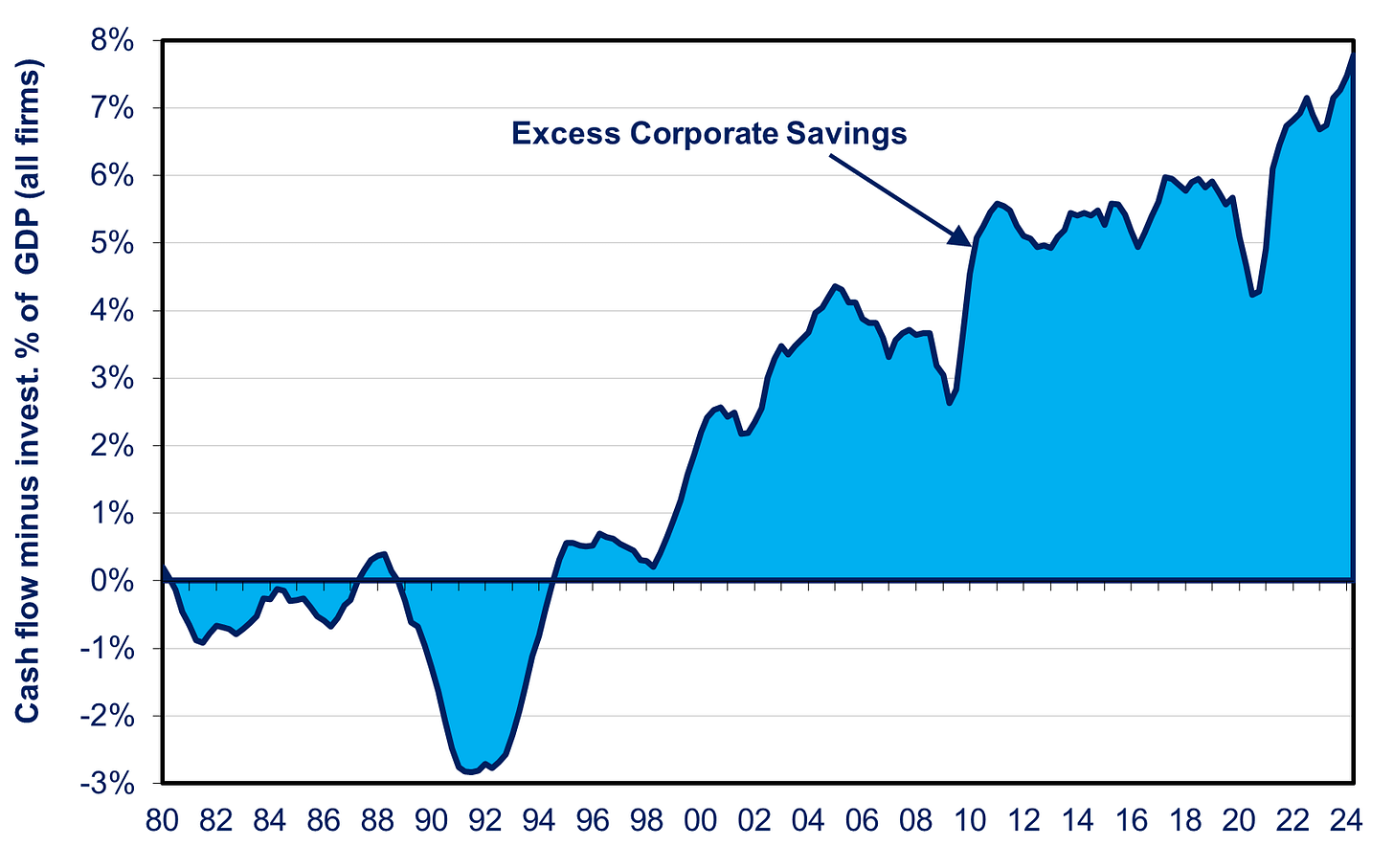

For one thing, Japan’s corporations are investing in too little plant, equipment, and software to absorb all of their cash flow, i.e., the savings that stem from profits and depreciation accounts. So, not only do corporations have little need for bank loans or issuance of corporate bonds, but they are hoarding their excess cash rather than spending it on wage hikes or returning it to investors in the form of dividends. Consequently, their annual excess savings keeps rising and now stands at 8% of GDP each year (see chart below).

Source: MOF at https://www.mof.go.jp/english/pri/reference/ssc/historical/all.xls

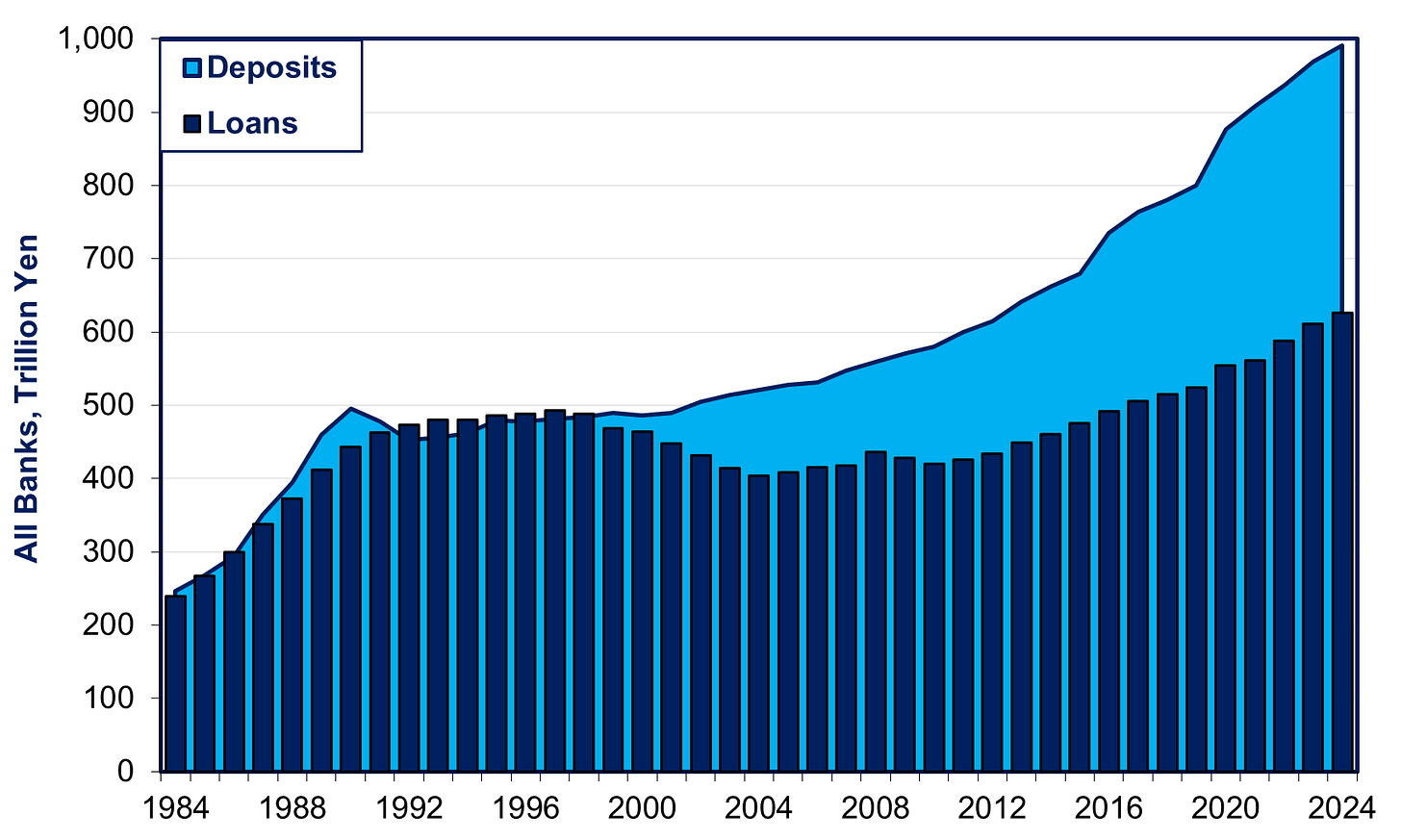

Given this shortfall in corporate demand for credit—as well as the slump in consumer demand for housing and auto purchases—Japan’s banks can no longer lend enough to use all the deposits that they take in. This contrasts with the earlier era when deposits and loans were in balance (see chart below).

Source: Bank of Japan Time Series

The result is that the interest rate on bank loans remains very low. 70% of all lending to business and consumers charge an interest rate of less than 1%, of which nearly a third charge less than 0.5% and 10% less than 0.25%. So, on a goodly portion of their loans, banks don’t even earn enough to cover their operating costs.

Moreover, since the banks have to invest all that deposit money in something, they buy JGBs, which now account for a third of all bank assets.

The So-Called “Neutral Rate” Of Interest

What does this low demand for credit mean for the US-Japan gap in long-term interest rates, and hence the yen? To answer that, we must ask: what is the interest rate in Japan at which the demand for credit equals the supply of savings? Economists call this the “the neutral rate of interest.” If the actual interest rate in the credit markets is below the neutral rate, the economy will overheat. If the actual rate is higher than the neutral rate, growth will slow, and the economy will operate at less than full capacity, as in a recession.

While the neutral rate cannot be measured directly, most economists, including those at the BOJ, think the real, i.e. inflation-adjusted, neutral rate has become negative during the last couple decades. The BOJ showed calculations using six different models, and five showed a negative real neutral rate. This ranged from negative 0.3% to negative 1.1%. Among other sources, Oxford Economics puts it at around negative 1.5% and believes it will stay negative for a long time, while the Japan Center for Economic Research estimates it at negative 0.5%.

The nominal neutral interest rate equals the inflation rate minus the real neutral rate. So, if Oxford is correct, then under 2% inflation, the neutral nominal interest rate would be just 0.5% (2% minus 1.5% = 0.5%). If JCER is correct, the neutral nominal interest rate would be 1.5%. The IMF believes it is somewhere between 1% and 2%.

I’m no forecaster, but all of this suggests to me that, even if Japan achieves 2% inflation by 2026, I’d not be surprised if the 10-year JGB rate remains closer to 1% than to 2%. If that’s the case, then there’d be slight narrowing of the 10-year US-Japan interest rate gap and thus relatively little yen recovery.

"Japan’s banks can no longer lend enough to use all the deposits that they take in"

Richard - sorry to be anal, but as Professor Werner has shown empirically, banks do not lend out deposits, they create new deposits from nothing when extending loans. Instead, deposits are invested in securities to generate a return. So unless I am missing something, there is no such issue of banks not being able to "use up" excess deposits.

Presumably instead the huge amount of corporate cash hoarding is actually providing banks with a safer and more liquid return than they would get on lending to corporates?

Hi, thanks for this interesting post. I always make time to read your articles.

If that’s OK, I’d just like to point out a couple of things. In the first chart, if the RHS axis is for the nominal yen (the yen per dollar rate) then it should be reversed (the axis, not the line). The all time high of the nominal yen (max yen strength, i.e. min yen per dollar) was in early 2012 at about 76. You can also see that your latest (2024?) observation is at around 100, while in actual fact it’s around 140.

It may also be worth checking the definition of your real exchange rate index (is up a stronger or a weaker RER?). The yen RER these days is at a point of multi-decade weakness, which makes Japan Inc. very (price) competitive as anyone who has travelled to Japan recently can attest to: Japan is cheap, i.e. the purchasing power of the yen is low/of foreign currencies high. That is a combination of both a weak nominal yen and of a low Japan price level relative to other countries (or chronically lower Japanese inflation).

Lastly, the contributor above is right to point out that banks create loans, and hence deposits (= money) out of thin air. This also means that the money multiplier (M/monetary base) is a meaningless quantity (the base is mostly central bank reserves, which must be held by commercial banks), banks “do not lend out” base money, they can just create deposits at will by deciding to lend. Borio and Disyatat of the BIS have some useful papers on this (around 2010-12), also see a nice Bank of England article called something like “Money creation in the modern economy”.

Your point about changes in the overnight rate differential not translating into an identical change in the 10y differential is a good one, with one caveat, however. During YCC, the (real) 10y JGB rate became the policy target of the BoJ, hence it correlated more closely with USDJPY than a short rate differential. They are now transitioning away from YCC (slowly), so the exchange rate may over time become more responsive again to the short rate differential.

Thanks again for a very useful post.

Regards, Spyros