Why Did The BOJ Move Despite Conflicting Evidence on Wages and Prices?

Tokyo Inflation Falling Below 2% Target

Source: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000032103981&fileKind=1

Why did the Bank of Japan (BOJ) rush to move now—ending negative overnight interest rates and Yield Curve Control (YCC) over longer-term rates—despite the lack of the preconditions the BOJ had previously insisted were necessary? Why, for example, not wait until June or July to see if the big wage hikes seen in the shunto negotiations spread into the general workforce? After all, they didn’t spread last year.

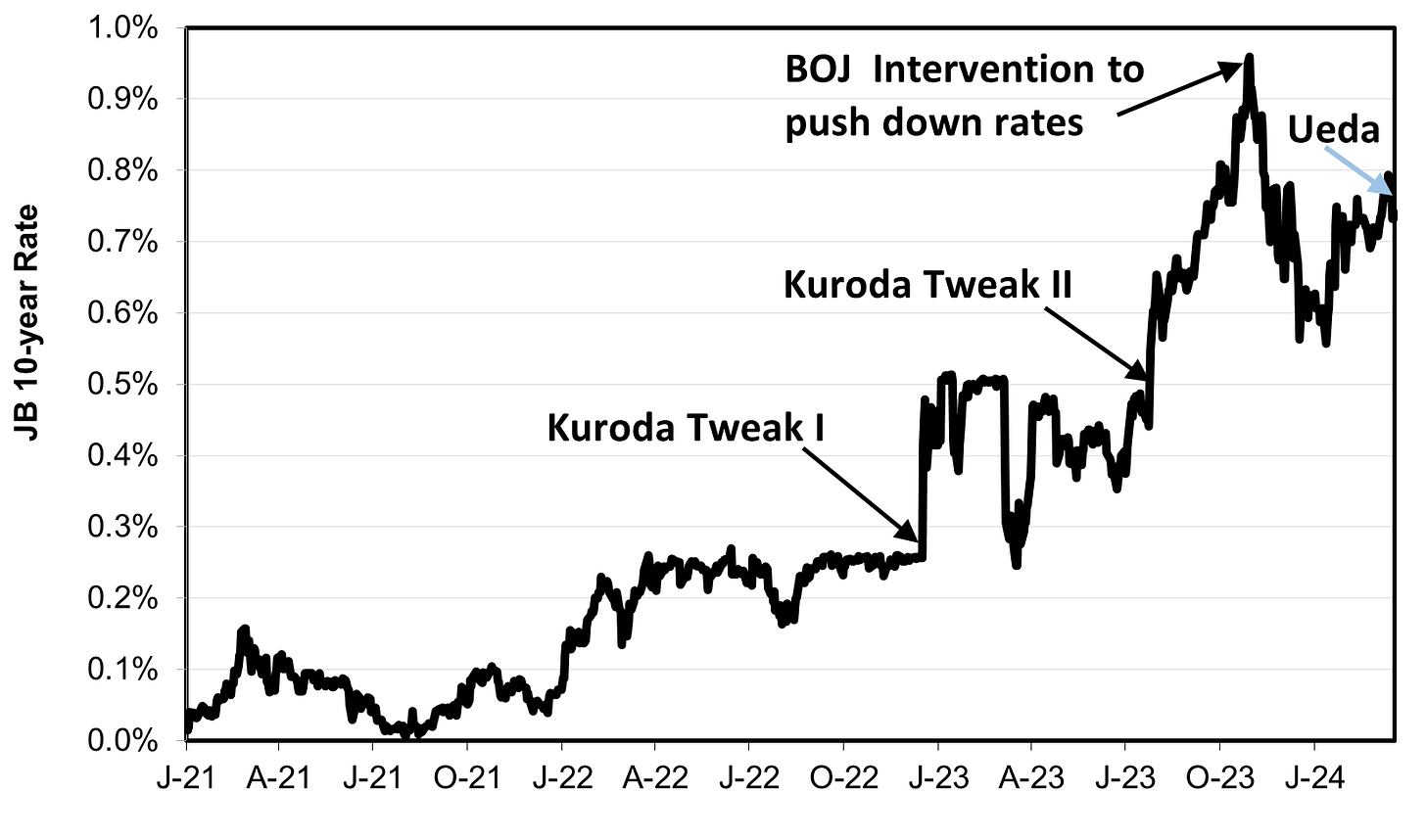

Moreover, why not wait until the inflation picture is clearer? As the BOJ had correctly forecast, the rise in imported inflation over the past couple of years was a temporary phenomenon. Still, it remains unclear how low inflation might go as this factor dissipates. Look at the results for Tokyo in February, which is a leading indicator for the nation as a whole. Compared to six months earlier, prices in February for the BOJ’s preferred measure—all items except fresh food—rose at an annual rate by only 1.7%, while prices excluding the volatile food and energy items were up only 1.2% at an annual rate (see chart at the top). Both are below the BOJ’s 2% goal.

Making the picture even more murky is the fact that government subsidies to wholesalers of energy products like gasoline and fuels for heating and cooking reportedly adds 0.5% to the headline inflation number and February is the first month to incorporate the year-on-year impact with the subsidies in place. That’s why I reported the ex-energy and food numbers above and looked at the six-month trend. It’s also unclear how long the subsidies will last since the government keeps extending them in an effort to boost its poor approval rating. They’re now extended through April. What happens when these subsidies end?

So, on what basis did the BOJ Policy Board decide that it had “assessed the virtuous cycle between wages and prices, and judged [that] the price stability target of 2 percent would be achieved in a sustainable and stable manner toward the end of the projection period of the January 2024 Outlook Report [i.e. March 2026]?” How does this square with the Board’s concluding comment: “there are extremely high uncertainties surrounding Japan's economic activity and prices, including…domestic firms' wage- and price-setting behavior [emphasis added]?”

No Financial Market Pressure Forcing BOJ’s Hand

Aside from a depreciating yen—at 151.5/$ as of this hour—there is little in the financial markets pressuring the BOJ to act now. There is none of the bond market pressure that led to Kuroda’s tweak in December 2022. Bond traders have not been pushing interest rates beyond the 1% ceiling on ten-year Japan Government Bonds (JGBs), which would have made it harder for the BOJ to enforce the ceiling. On the contrary, ten-year JGB rates have fluctuated around 0.7% lately, and they even fell a bit after the Tuesday announcement (see chart below). Moreover, Ueda stated at his press conference that he sees the risk of inflation too low as greater than inflation too high.

Source: Wall Street Journal

Did Ueda Decide Back In December?

Things changed in December when Ueda gave an interview saying that it might be sufficient for a policy tweak to see the results of this spring’s shunto negotiations. “It’s possible to make some decisions even if the Bank doesn’t have the full results of spring wage negotiations from small- and middle-sized businesses.” So, when the initial hikes were at the 5.3% level, the BOJ made the tweak.

This lends credence to a Reuters report that Ueda and his two top deputies had already decided back in December to end negative interest rates on overnight funds and to end firm ceilings on longer-term bond rates, i.e., YCC. The only question was one of how soon, and whether or not to follow that move with a series of increases in the overnight rates. There was a debate among the two deputies and Ueda decided not to proceed with a series of rate hikes. Deputy Shinichi Uchida’s February speech outlined the policy to prepare the market. So, it looks as if the BOJ was looking for an excuse to tweak and the shunto gave it to them. The Reuters report was based on interviews with two dozen sources, including BOJ officials. A BOJ spokesperson declined to comment when Reuters asked it.

In fact, one source familiar with the BOJ’s deliberations said Ueda decided to move now because there was some danger than inflation might drop below 2% for a while, forcing the BOJ to delay the desired tweak. “With the economy lacking momentum, there was a growing feeling within the BOJ that inflation might not stay around [i.e., at or higher than] 2% that long….The BOJ leadership probably realized that time was running short, if they wanted to end negative rates.”

Moreover, since the BOJ’s current stance is for the Bank to maintain an “accommodative” monetary policy even while it tweaks its instruments, Ueda stated at his press conference that, “I don't think deposits or lending rates will rise sharply from today's decision.”

Conflicting Evidence On Wages

Up until now, the BOJ had consistently declared that it wanted clear evidence that domestic demand-led inflation was moving sustainably to 2% based upon sufficient ongoing nominal wage hikes for all employees. Former Governor Haruhiko Kuroda used to specify this meant wage hikes of 3%. With productivity growing around 1%, wage hikes of 3% mean a 2% increase in wages per unit of output (known as “unit labor costs”). Kazuo Ueda, however, has not put out a specific number, just something meaningfully above the 2% inflation goal.

The problem is that different databases give very different, even contradictory, evidence of wage trends.

First, there is the most basic database for wage hikes. It shows a saw-toothed pattern for hikes in nominal wages per hour compared to the year before (see chart below). It counts only scheduled hours since the results can be distorted by the zigs and zags of overtime and occasional months where bonuses are paid. Rarely in the last few years has this measure gone above 2% and only once has it hit 3%.

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/monthly-labour.html

The problem is that the survey does not poll workers at the same firms every month and so comparisons are unreliable. Hence, the BOJ prefers another database where the same sample of workers is surveyed. By contrast, this shows a steady increase in nominal wages over the past few years to a level of around 2% in the past 7 months (see chart).

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/30-1a.html

The problem here is that the sample size is much smaller, and it is unclear whether the size of the firms polled is representative of the whole labor force. This is important because wage trends differ greatly depending on firm size and the ratio of non-regular workers to the whole sample. Moreover, 2% inflation requires wage hikes substantially above 2%. That has not yet occurred.

The whole notion that consumer inflation depends on nominal wage hikes relies on the notion that consumer inflation more or less matches growth in “unit labor costs,” i.e. the annual increase in the wages a firm must pay to produce a ton of steel or a car of equal quality or the same level of service at a bank or store. The premise is that employers pass on to the consumer that increases in unit labor costs. In reality, this supply-side (i.e., cost) measure is only part of the set of factors influencing core inflation. The demand side, i.e., consumer spending, is at least as important. Moreover, a government survey of small and medium enterprises last year showed that they could only pass on to their customers 46% of their cost increases.

Worse yet, another government database shows that, in recent months, unit labor costs have barely increased (see chart below). That is a clear contradiction with the data provided in the chart at the top, the BOJ’s preferred source. However, the BOJ disregards the unit labor cost measure as an unreliable guide because it comes with a delay and is often subject to substantial revision.

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/30-1a.html

Finally, even though nominal wages are rising, real after-inflation wages have fallen for the past 22 months, just as they have during much of the past decade (see chart below). This raises a big question. Will substantial hikes in nominal wages continue as inflation falls, thereby finally causing real wages to rise? Or, is the rise in nominal wages just a means of preventing real wages from falling too much? If it’s the latter, then as inflation recedes, so might the rise in nominal wages. In that case, real wages would continue to fall. The latter is hardly a good sign for consumer spending, which is at least as important as unit labor costs in the inflation rate.

Source: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/monthly-labour.html

With all this conflicting evidence, the bottom line is that the prospects for nominal and real wages over the coming few years are highly uncertain, and so are the prospects for inflation.

Central banks often are compelled to make judgment calls before the desired evidence is in. Failure to decide is also a decision. But in the case of this BOJ move, there does not seem to be any such compulsion. If, when March 2026 comes and both wages and inflation fall short of the BOJ’s forecast, how will the BOJ explain its rush to tweak?

No the BOJ risks being a partner in inflating an equity bubble leading to another round of deflation as it the bubble is burst.Just have to see if the NIKKEI rally has feet of steel or clay and time to raise the cost of capital

Excellent, Richard. You have done my homework for me. If I may ask: Will coercive wage hike-by-jawboning measures work? Since even big, cash-rich companies don't believe they can justify big wage hikes in the long term, aren't they just effectively bowing to pressure to fork out some of the cash they have hoarded to weather an uncertain future? Even if the big boys can do this to avoid be targeted for ijime by the bureaucrats, many small- and midsize companies face certain death if they raise their wages too high. The central problem is that nobody, not the LDP, not METI, not the MOF, not the Keidanran, not the Shokokai, believes in Japan's future. In this milieu, trying to jawbone up wages is almost suicidal, I think. Personally, I would prefer to see a new focus on making consumer goods cheaper, which makes a stagnant wage go much further. The mantra of eternal growth does not apply to Japan's demographic situation, I think. Japan's economy needs to learn how to enjoy getting smaller. In this, they could become an OECD leader.