Source: https://www.spglobal.com/en/research-insights/special-reports/china-ahead-in-delivering-affordable-electric-mobility Note: BEV = battery-operated EVs; ICE = gasoline-only Internal Combustion Engine cars; Hybrid = conventional (HEVs) and plug-in (PHEVs

FLASH: Polls by Yomiuri and Asahi and Mainichi suggest the LDP-Komeito coalition could lose its majority in the upper house in this coming Sunday’s election. But 40% of voters are still undecided as of a couple weeks ago, so it will be a nail-biter. The big surprise is the rise in polling of the new xenophobic Sanseito party to second place in support rates for parties.

In Part 1, I showed how the top two Chinese automakers have overtaken all the Japanese producers except Toyota in total global sales. Moreover, Japan’s overall share of the global auto market is steadily shrinking. Up to now, Toyota has been the exception, more or less maintaining its global market share (see chart below).

Source: https://www.factorywarrantylist.com/car-sales-by-revenue.html; https://www.statista.com/statistics/262747/worldwide-automobile-production-since-2000/ Note: 2025 includes Jan-April; includes light vehicles, trucks, and buses

However, if mainstream forecasts for battery-operated electric vehicles (BEVs) prove correct (see chart at the top), Toyota’s share in 2030 will likely be substantially smaller than it is today. The main reason is Toyota’s stubborn, almost ideological, refusal to see the potential of BEVs.

Toyota management is more convinced than ever that it is calling market trends correctly. Toyota points to its high sales and profits during 2023 and 2024 because it stuck to hybrids (HEVs) when the market for BEVs hiccupped in 2024. While the company calls its strategy “multi-pathway,” in reality, BEVs and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) play only a fringe role. In January-May 2025, BEVs amounted to a piddling 65,000, just 1.4% of Toyota’s total output. In my opinion, there are some very big flaws in Toyota’s view of both the market and itself.

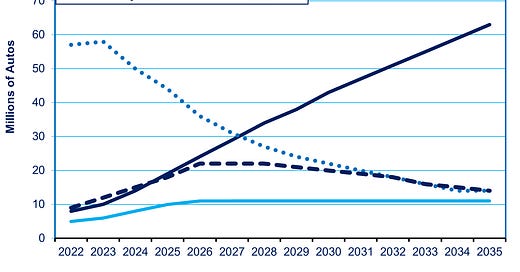

True, mainstream forecasts now see BEVs taking longer to reach dominance than they foresaw a couple of years ago. Nonetheless, they still believe that, within five years, BEVs will strongly outsell HEVs and PHEVs, not to mention gasoline-only Internal Combustion Engine vehicles (ICEs). The first quarter of this year saw a stunning 42% year-on-year global rebound in BEV sales, compared to 26% each for PHEVs and HEVs. S&P believes HEV sales will peak around 2028 at 22 million vehicles and then plunge to just 14 million by 2035 (see top chart again). To its credit, Toyota has been quicker than others to move away from ICEs, whose 2024 sales were 27% below its peak level in 2017. But, instead of offering a balanced menu, Toyota is acting as if HEVs will dominate well into the future.

Remarkable profits today are not necessarily the harbinger of similar profits tomorrow. GM enjoyed record profits in 1989, just before three consecutive years of record losses in 1990-1992 brought it “one FAX away from bankruptcy.” About five years after earning record profits, IBM faced a similar near-death experience around the same time as GM. Fortunately, IBM was willing and able to change its business model. GM, on the other hand, has shrunk, selling a third fewer autos worldwide than in 1979. Its global market share has plunged from a staggering 27% to just 7%.

It is often the most successful companies that find it the hardest to see that times have changed. Mistakes are, of course, inevitable in a world of uncertainty. Beyond that, however, older corporate stars suffer from a biased perception fueled by a desire to cling to the strategy that brought them success. In a classic case of “confirmation bias,” executives read every positive result as the universe signaling them to stay the course. Conversely, they downplay adverse outcomes. Japanese giants are particularly vulnerable due to their system of promotion from within. Protégés (kohei) hesitate to abandon the path set by theit mentors (sempai). Insufficient mid-career hiring deprives them of the needed infusion of a fresh perspective. I elaborate on this in Chapter Four of The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future and recommend the classic The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail.

Worse yet, huge “sunk costs” add a financial incentive to wear perceptual blinders. Having made enormous investments in physical capital and in training staff in a specific mode of thinking, they fear new products that would prevent them from recouping that investment. Kodak invented digital photography but chose not to embrace it, lest it cannibalize its investments in film. It left that to competitors and went bankrupt in 2012. Scores of big companies create or buy patents, not to use them, but to prevent others from introducing new products. That’s another reason it often takes new companies to pioneer new technologies.

Toyota is accumulating enormous “sunk costs” in hybrids. As a result, not only is Toyota lagging on BEVs, it is aggressively trying to hinder others from making BEVs popular, e.g., its aid to anti-BEV Republicans in the US, as detailed in Part 1. The bigger Toyota’s profits today, the less likely it is to see the need for change.

Toyota Says Its BEV Projections Through 2030 Are Not Really Targets

If you seriously doubt Toyota’s repeated declarations that, by 2030, it will produce 3.5 million BEVs, more than 30% of its total global sales, don’t worry. Toyota doesn’t believe it either. While denying reports by Nikkei that it has halved its plan to produce 1.5 million BEVs next year, it added that its numbers are not targets but merely “benchmarks” for shareholders. That, I guess, means a number aimed mainly at buoying its share price.

So, I believe Nikkei when it reports that Toyota has alerted some of its suppliers that it will only produce 800,000 in 2026 and only 1 million in 2027. Given that Toyota’s BEV sales amounted to an annual rate of just 156,000 during January-May—compared to a 2023 announcement that it would sell 600,000 this year—it does not seem on track to get to even close to 800,000 next year.

Other legacy companies are far more serious. Compare Toyota’s 35,000 BEVs sold in January-March (just 300 of them in Japan) to VW’s 220,000 and BMW’s 110,000. Both have overtaken Tesla in Europe. GM, new to the BEV game, doubled its sales in the first half of 2025 to 78,000, including a Chevy priced at $35,000. It is now second to Tesla in BEV sales in the US. Meanwhile, Toyota fell further behind as its share of global BEV sales slid from 1.4% in 2024 to 1.1% in January-May.

By the way, the hydrogen fuel cell (FCEV) chimera, on which Toyota still wastes so much money, could lure only 1,800 customers last year, half as many as in 2023.

Toyota’s Hybrid Focus Faces More Players Fighting For A Market Doomed To Shrink

Rather than diversify, as it claims, Toyota is turning itself into an HEV company. In January-March, HEVs constituted 41% of its total global vehicle sales. It will soon offer only hybrid versions of almost every model. This year, the Camry, Land Cruiser, Sienna, Venza, and Sequoia will only come in HEV versions, and the same will be true of its RAV4 next year.

Here’s Toyota’s problem. As noted above, S&P forecasts that sales of HEVs/PHEVs will peak in just a few years. If S&P and other mainstream forecasters are right, Toyota is betting its future on a shrinking market. To make matters worse, new players are moving into hybrids. So, while Toyota currently enjoys a 31% share in global hybrid sales, it could be left with a thinner slice of a shrinking pie in just a few years.

The Threat From EREV Hybrids

Here’s yet another threat. Chinese companies have successfully resurrected a technology pioneered by BMW and GM more than a decade ago, called an Extended Range EV (EREV). It never took off then, but is doing so now in China, where EREV sales almost doubled in 2024 to 1.2 million vehicles. Four of the top 10 PHEVs sold globally during the first 10 months of 2024 were Made–in-China EREVs. That is causing companies like Hyundai, Stellantis, Jeep, VW, and Ford to launch their own efforts. But not, as far as I can tell, Toyota. Nissan’s E-Power vehicle is different and more expensive but could also cut into Toyota’s hybrid sales.

An EREV runs on electricity, but just for 100-200 miles. Its advantage is that it can extend its range to 400 miles while costing thousands of dollars less than an HEV or PHEV. It does so by having a small gas engine that only acts as a generator to recharge the batteries. Those with access to a plug-in charger may rarely use the gasoline extender. It costs less since the battery is smaller and because it has just one power train, not two like a hybrid. There is no range anxiety since finding a gas station is easy. Finally, it emits less carbon because, as Google reports, EREVs often exceed 100 MPGe, followed by PHEVs in the 70-90 MPGe range, and HEVs in the 40-60 MPG range.

McKinsey calls the EREV the best transitional option to BEVs until the latter’s prices come down sufficiently and infrastructure is built up.

Falling Behind The Learning Curve

Toyota and its compatriots may believe that, if need be, they can rev up production and put out competitive BEVs whenever they want to. However, fabricating a BEV requires very different methods from making an ICE or HEV. When a product is new, companies get better at production and marketing via the “learning curve,” i.e., learning by doing. Economies of scale means that you can produce cars more cheaply if you make 100,000 of a model in a given year rather than 10,000. By contrast, the learning curve means that, over the years, you can cut costs, improve quality, and ensure your models fit customers tastes as your cumulative production goes from 100,000 to 1 million to 30 million. Each time the total installed capacity of solar modules doubled over the past 50 years, the price fell by 20% on average (see chart below).

So, companies which produce too few units for too long may find it harder to catch up to the leaders, even companies with immense technological prowess. SONY found this out when it repeatedly tried, and failed, to put out a competitive personal computer or smartphone. As of this spring, BYD had produced 11.6 million BEVs, Toyota less than 325,000.

As a detailed Bloomberg analysis points out, the Toyota Production System is based on day after day of incremental improvements (kaizen). However, the production system for a BEV is very different from an ICE or HEV. The BEV has thousands of parts that are either new or put together differently than in a Camry or a Prius. “You cannot kaizen yourself from an ICE vehicle to a BEV. That is the dilemma for Toyota,” Bloomberg was told by Terry Woychowski, a former General Motors executive who is now President of Caresoft. The latter is a reverse-engineering company that counts Toyota among its clients. Moreover, engineers brought up in one system cannot easily adopt the mindset needed by a new system. As Bloomberg put it, “A tilt toward custom gear means late adopters, even those with lots of cash on hand, will find it tougher to simply copy and improve upon the things the early movers figured out.” When Toyota collaborated with BYD to produce a BEV model for the Chinese model, bZ3, Toyota engineers were “flabbergasted” by the Chinese engineering approaches.

By producing so few BEVs, and failing to use their own country as a foundation, Toyota and other Japanese automakers are falling behind on the learning curve. Trump’s attacks on EVs are handicapping American companies. Meanwhile, during January-June, BYD’s global auto sales rose 33% to 2.15 million, and overseas sales more than doubled to accont for 21% of all sales. BYD has now surpassed Tesla as the world’s top BEV producer. Seems that Trump and Toyota are out to “Make China Great Again.”

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The link for the McKinsey article is broken.

"However, the production system for a BEV is very different from an ICE or HEV. The BEV has thousands of parts that are either new or put together differently than in a Camry or a Prius. “You cannot kaizen yourself from an ICE vehicle to a BEV. That is the dilemma for Toyota,” "

I don't think that is true. The move from (P)HEV to EREV should be easy and one that Toyota can do. PHEVs have electric motors and batteries and gasoline motors as do EREVs. The difference is that the EREV loses all the ICE powertrain and simply connects it to the battery charger. Essentially you remove the ICE powertrain and probably add a second electric motor on the other axle. That's an evolutionary change and I can't see why it would be hard for Toyota.

In fact that EREV makes the FC vehicles possible too - just replace the gasoline motor with the hydrogen FC and have the FC charge the batteries when needed.