What Kishida Should Have Done On Wages, Taxes

An Agenda For The Distribution Side of The Growth-Distribution Virtuous Cycle

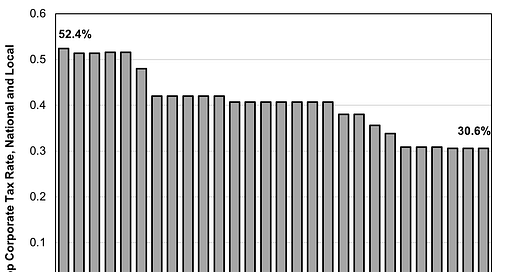

Source: National Tax Agency as cited in https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/corporate-tax-rate

In our last post, we showed how Prime Minister Fumio Kishida retreated from any solid measures to advance his mantra of the “virtuous cycle of growth and distribution,” leaving only some hollow rhetoric. But let’s imagine that, with an Upper House victory under his belt, Kishida became more assertive in the “five-year plan” due at year’s end. If so, what steps should he take on the distribution side? We had discussed the entrepreneurship plank within the growth strategy earlier.

The primary culprit in the stagnant incomes of most Japanese is not the country’s few truly wealthy citizens. It is the gap between corporate and household incomes. Corporations are hoarding “retained earnings,” i.e., profits that they do not plow back into the economy via wage hikes, investment, or even taxes. Worse yet, over the past couple of decades, Tokyo has repeatedly shifted income from households to companies by raising the consumption tax to help finance tax cuts for companies. The government slashed the top corporate tax rate on large companies from a peak of 52% of profits in 1994 to 30% at present (see chart above).

Keidanren (the big business federation) and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) claimed that everyone would benefit from corporate tax cuts because companies would use the extra cash to spend more on wages and investment, thereby boosting per capita GDP. In effect, Tokyo made a deal with companies: If we cut your income taxes, you’ll raise wages. However, corporations never fulfilled their end of the bargain.

At their November 26 meeting, New Capitalism Council members were given materials illustrating how badly this deal had failed. Between 2000 and 2020, the combined yearly profits of Japan’s few thousand largest corporations almost doubled (up ¥18 trillion or $132 billion), but their compensation to workers fell 0.4% and their capital investment fell 5.3% (see chart below).

Source: Ministry of Finance data cited in https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=882

As a result, the corporate giants’ cumulative retained earnings soared by a mammoth ¥154 trillion ($1.14 trillion). That equals almost a third of a year’s GDP. Had companies instead spent that excess cash on wages, living standards today would be significantly higher and so would consumer demand. The same pattern prevailed at incorporated SMEs, where hoarded cash grew while worker compensation fell.

This pattern is exactly what Kishida was referring to when he correctly said that neither healthy growth nor healthy distribution could exist without the other. How can the economy grow if workers do not earn enough to buy what they make? Why would companies invest in expansion if they cannot sell their products at home and can only sell abroad if the yen gets weaker and weaker? In the entire OECD, Japan shows the biggest gap between the increase in GDP per hour of work and wages per hour. And, of course, hikes in the consumption tax suppress consumer demand even further.

And yet, the Council failed even to discuss this data, according to the minutes of the meeting. The only reason we know that Council members saw this information is that this was reported by Shigeki Morinobu, a former MOF official now at the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research (as shown in the chart above).

If corporate income tax cuts are worsening Japan’s growth and its budget deficit, why not roll them back? Why not use the resulting revenue gains to reduce the consumption tax? That would create a fairer distribution of income between companies and households? No one in the Council even mentioned this option.

Why not take steps to ensure that corporations hike wages? For example, Japanese law already mandates equal pay for equal work between regular and non-regular workers and between men and women. Yet, no agency of government is mandated to investigate violations and penalize offenders. By contrast, in France, labor inspectors seek out such violations and the government has already fined a few companies for paying women less. Once again, no one discussed using Japan’s labor inspectors in a similar way.

Raising the minimum wage has surprisingly powerful ripple effects. It not only elevates the income of those below the minimum wage but also those earning 15-20% above it. Since the average wage of part-time workers is just ¥1,100 ($8.20) and they comprise almost a third of all employees, the impact on living standards and consumer demand would be dramatic. Unfortunately, Kishida only reiterated the minimum wage goal enunciated a dozen years ago, ¥1,000 per hour, without stating when he would reach this goal. The minimum is now ¥930. Nor did he raise the possibility of raising it beyond ¥1,000. Among 21 OECD countries, Japan comes in 18th with its 2020 minimum wage just 45% of the national median wage. In the typical rich country, it’s 52% (it takes half of a country’s median income to rise above the poverty level). Japan should set the rich country standard as its goal. These days, that goal would require a minimum wage of around ¥1,145.

Regarding the goal of a tenfold hike in new companies, a specialized group of genuine experts was given six months to come up with a wide variety of imaginative ideas. By contrast, the Kishida administration created no similar advisory group on fixing today’s vicious cycle between growth and distribution. Hence, the ideas approved in June were hardly different than those discussed back in November. This approach exacerbates worries that Kishida’s cave-in on distribution policy will last.

For fuller articles in Toyo Keizai on this topic, see https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/596702 in Japanese and https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/597075 in English.

How would your ideas sit with (foreign) shareholders who are hoping finally to unlock some returns from Japan Inc.?

It appears that you are looking for more command and control from the Japanese government. Exactly what you don't want. The issue continues to be the banking system. Japan has a very weak banking system. Banks are not allowed to earn enough profits. Japan has "protected" depositors from charges and not allowed banks to maximize profits. If banks were much more profitable they would be able to take on more risk and companies would not feel the need to protect themselves by holding cash.

Fix the legal system. The system does not allow for financial innovation -- this is also why Tokyo will never be a financial center. You can only release a financial product after it has been OK'd by the government. By that time it is no longer an "innovation." With better access to the bond market and the ability to do a Chapter 11 type bankruptcy there would be less need for SMEs to hoard cash.

Forcing higher wages does not help. Promoting liquidity in the human resources market would make a bid difference. Focus on getting people out of companies that don't need their skills and into companies that need them... You are then forced to pay for an employees ability -- they are not locked into their employer.

There are so many things Japan needs to do. You are focusing on ones that are very short term and do little to build a system for the future.