Would Yen Intervention Succeed?

¥154/$: Is it Based On Fundamentals or Speculation?

Source: Wall Street Journal

Ever since the yen weakened to ¥150/$ a month ago, currency traders have been talking about whether (or at what level) the Ministry of Finance (MOF) would intervene in the currency markets. Since then, the yen has passed many “red lines”: ¥151, ¥152, and ¥153. Today, in the aftermath of the Iranian attack on Israel, the currency weakened to just ¥154.2/$, a level last seen way back in 1990. And yet, at least so far, the MOF has done nothing more than issue statements of what it might do.

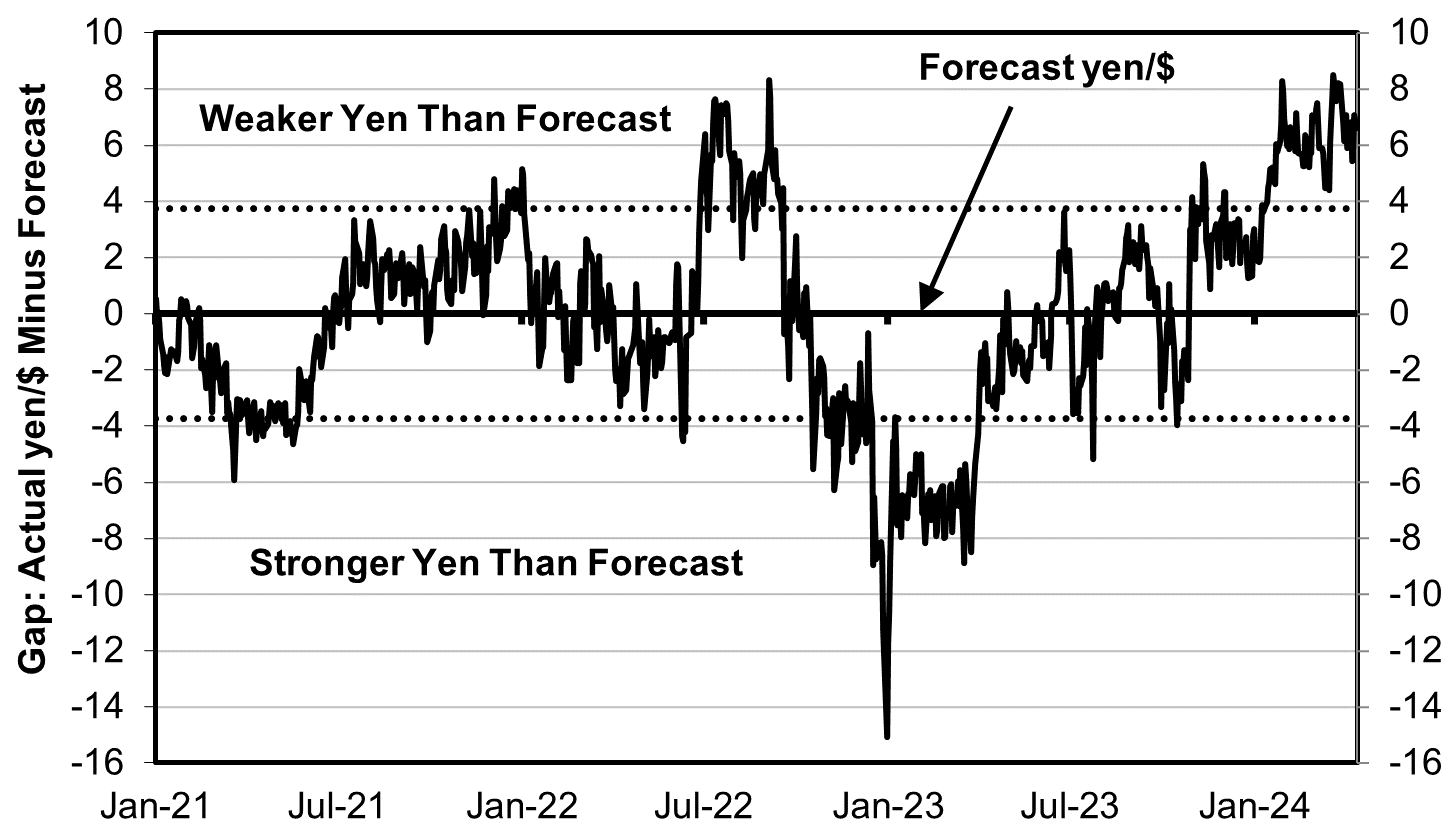

Suppose the MOF does intervene, would its effort succeed? Its track record on this is not good. Back in September-October 2022, when the yen hit ¥150, the MOF spent a stupendous ¥9.19 trillion, almost 2 percent of GDP, and it had no discernible impact. We can see this in the chart at the top. Over the past three years, the ups and downs of the yen have been primarily determined by the ups and downs of the gap between American and Japanese rates on 10-year government bonds. When the gap gets higher, money is lured from Japan to the US. Those purchases of US financial assets create demand for dollars, which raises its value and lowers that of the yen. When the gap gets smaller, less money flows to the US and the yen recovers somewhat. In fact, an extremely high 94% of the daily ups and downs of the yen’s value can be explained simply by looking at the gap in interest rates. One need not even look at the trade balance, the price of oil, wars, and such. In the chart above, the yen’s path followed the interest rate gap so much that you could not even tell when the MOF intervened if I had not put in labels to show it. A yen at ¥150 was awfully weak, but it was more or less exactly where the interest rate gap said it should be.

To be sure, there are times when intervention can succeed. That occurs when a currency is out of line with fundamentals. That was decidedly not the case in 2022. Is that the case now? It could be, but, if so, not by very much.

Is the Yen Too Weak?

As we can see in the chart at the top, for the past few months—the area inside the oval on the upper right—the yen has been noticeably weaker than one would predict from the interest rate gap. In fact, as of today, a prediction based solely on the interest rate gap would predict a yen of ¥147.6, but the yen is 6.6 points weaker. Is that a big deal? As the chart below shows, on two-thirds of the days over the past three years, the yen is no more than 3.7 points distant from the forecast level. So, the yen is somewhat weaker than that boundary. But that’s hardly unique. The chart below shows the same thing from late 2002 to early 2023 and an even bigger deviation—a yen stronger than forecast—in much of the first half of 2023.

Source: Author’s forecast based on interest rate gap compared to actual yen/$ rate

There are three possibilities: the yen/$ will sooner or later move closer to the forecasts as happened before; the yen is too weak due to unwarranted speculation; or some other factor is causing a downward ratchet of the yen as has happened before. One of those factors could be a risk-creating incident like a war.

The bottom line? I’m not a currency forecaster, but my gut feeling is that, if the MOF does intervene, it would most likely have just a temporary effect or a small one. It might even fail as badly as in 2022.

What About BOJ Action?

More effective than MOF intervention would be a tightening of interest rates by the Bank of Japan (BOJ), which, if not matched by changes in the US, would narrow the interest rate gap. BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda was asked in Diet testimony whether a weakening yen might lead to a change in BOJ policy. He said it might but only if a weak yen caused higher-than-desired inflation. “If there is a risk that a virtuous cycle of wages and prices strengthens more than expected and underlying inflation rises above 2%, we need to consider changing monetary policy.” By the way, he also said the BOJ tweaked policy in April because it feared that failure to do so then might cause inflation to overshoot its 2% target.

The Real Fundamental Behind the Weak Yen

So far, I have written as if the interest rate gap were the lone fundamental behind the yen’s value. But that is only how things work in the short-term of a few years, or perhaps several years. From a longer term perspective, the yen is so weak because the Japanese economy is weak. Many of Japan’s companies have lost so much of their past competitiveness that they can no longer export as much unless they sell their products at very low prices, and that requires a cheap yen. I’ve written about this in past blog posts as well as op-eds.

To see how cheap the yen really is, the best measure is not the market rate vis-à-vis the dollar, but a measure called the “real effective yen.” This shows the real value of the yen against, not just the US dollar, but vis-à-vis all of Japan’s trading partners and adjusts the market rate by the relative rates of domestic inflation and deflation (for reasons not worth going into here). Today, the real effective yen is weaker than it has been since figures started being kept going back more than half a century ago (see chart below).

.Source: Bank of Japan

Despite this record cheapness, Japanese companies still find it hard to sell their wares. For the 30 years to 2010, whether the yen was strong or weak, Japan ran trade surpluses every year but one. Since 2011, however, the country has suffered trade deficits in ten of the past 13 years, even though the real effective yen during the last decade was 25 percent cheaper than it was during 1980-2010.

This result flies in the face of hopes by Shinzo Abe that weakening the yen would revive Japan’s GDP growth by boosting the country’s trade surplus.

Why the BOJ Cannot Revive The Yen Very Much

One result of this fundamental deterioration in Japanese competitiveness is the following: for any given interest rate gap between the US and Japan, the yen is about 20 points or so weaker today than it was a couple of decades ago. During 2001-2013, when US interest rates were 3.7% higher than those in Japan, the yen’s predicted value was around ¥126. Today, it’s 21 points weaker at ¥147, and its actual value even weaker at ¥154 (see chart below).

Source: Author’s calculation

So, even if the Bank of Japan raises interest rates and the Federal Reserve lowers American rates, thereby narrowing the interest rate gap, the yen’s value is not going to go back to anything close to where it was during the 2001-13 era.

On some days:

The main conclusion remains the same though: unless Japan’s fiscal policy changes, or the US seriously cuts interest rates, and/or Japan’s economic fundamentals change, an intervention will probably not be very effective.

In more simple words:

In a simple model where interest rate gap is the main factor behind exchange rate moves:

(Referring back to my original metaphor of water) Water will flow as long as there is a significant difference in level (not only when the difference increases).

Therefore I would think that the area in the rectangular on your chart is as expected (and not a yen weaker than expected/predicted).

And indeed we saw the same in the period 2012-2015, when gap was high but did not increase (actually slightly decreased) and yet the yen kept going down.